Fifty years ago this summer, Scientology mounted a lengthy and concentrated campaign to take over Britain’s National Association of Mental Health (NAMH). Driven by L. Ron Hubbard’s paranoid belief that he and Scientology were being targeted by a supposed global psychiatric conspiracy, Scientologists attempted to infiltrate the NAMH ahead of its annual leadership elections and take over the organisation. It was a vivid demonstration of Hubbard’s hatred of psychiatry and his followers’ willingness to put his anti-psychiatric agenda into practice.

Seized and leaked Scientology files and the NAMH’s own internal files — now accessible at the Wellcome Institute in London — allow both sides of the story to be told in greater detail than ever before. They show that despite the campaign’s high profile, it proved not only to be a failure but resulted in the NAMH becoming a much stronger and more effective organisation as it responded to Scientology’s aggression. It also had lasting consequences, continuing to this day, for how Scientology approaches its perceived enemies.

Based in Westminster in London, the NAMH was a charity formed in 1946 from three previously separate voluntary mental health organisations. It campaigned for better mental health treatment and provided support to the mentally ill and their carers with the aid of government and private funding.

Despite Hubbard’s conspiracy theories about it, the NAMH did not run or license psychiatry in the UK; it was simply a campaigning and support organisation for people suffering from mental illnesses. Destroying it, as Hubbard desired, would simply have left the mentally ill even more vulnerable than they already were.

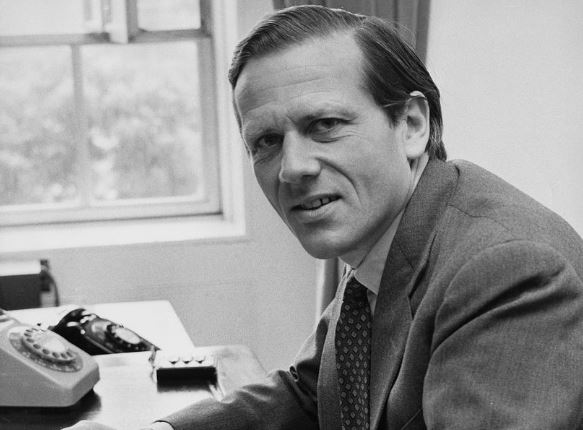

The NAMH was one of the UK’s most influential voluntary bodies. This was reflected in the people associated with it. At the time of Scientology’s campaign against it, it was headed by former Conservative Deputy Prime Minister Lord Butler and counted the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Chief Rabbi among its vice-presidents. Lord Balniel, the first person to ask a question about Scientology in the British Parliament, was the chairman of the NAMH’s governing council. One of its former Directors, Kenneth Robinson, became the Minister of Health who introduced immigration restrictions on Scientology in 1968.

The NAMH had become interested in Scientology around 1960, after Hubbard set up operations at Saint Hill Manor. It received a steady stream of complaints about Scientology from those affected by its activities. The 1965 publication of the highly critical Anderson Report on Scientology in Victoria, Australia “confirmed the fears of NAMH that Scientology would tend to exploit individuals who were inadequate or anxious,” according to a chronology subsequently compiled by the NAMH. It prompted Lord Balniel’s February 1966 question to the Minister of Health.

In an almost certainly related move, the NAMH began to collect press reports on the Scientologists’ activities in a file kept by the Public Information Department. However, as an internal NAMH memo reported laconically, “this file disappeared at the end of 1966.”

Lord Balniel’s question produced a furious response from Hubbard. He ordered his staff: “Get a detective on that lord’s past to unearth the tid-bits. They’re there.” He sought to recruit several private detectives to find “at least one bad mark on every psychiatrist in England, a murder, an assault, or a rape or more than one,” starting with Lord Balniel. The goal was to eliminate every psychiatrist in the country.

Within days of Lord Balniel’s question, Hubbard set up a “Public Investigation Section” within Scientology to direct the activities of its investigators. The purpose of the new section was stated to be “to help LRH investigate public matters and individuals which seem to impede human liberty so that such matters may be exposed and to furnish intelligence required in guiding the progress of Scientology.” This became the mission statement of the Guardian’s Office (GO), established later in 1966 to replace the Public Investigation Section. It is still the mission of the Office of Special Affairs today.

As part of the campaign against the NAMH, Scientology created a “Facts for Freedom Committee” in the UK which collected allegations of psychiatric mistreatment and abuses, sent out questionnaires and approached public figures. It also established a “Campaign Against Psychiatric Atrocities” which staged demonstrations outside the NAMH’s headquarters and psychiatric institutions. Groups of Scientologists waved banners such as “Psychiatrists make good butchers,” “Psychiatry kills,” and “Buy your meat from psychiatrists,” and handed out Scientology literature to perplexed onlookers.

After the NAMH’s journal Mental Health reported in September 1966 on Lord Balniel’s criticism of Scientology in Parliament and Hubbard’s recent expulsion from Rhodesia, the Scientologists responded by suing it for libel. A follow-up report on the March 1967 parliamentary debate on Scientology led to further libel claims. The Scientologists accused the NAMH of “advocating brutal and savage treatment of the insane” and “insinuat[ing] one of its officers, Kenneth Robinson” into the Ministry of Health.

The NAMH’s General Secretary, Mary Appleby, appeared in a Spring 1968 television debate with David Gaiman, the GO’s head of public relations and Scientology’s chief spokesman (and fantasy author Neil Gaiman’s father). She characterised Scientology as “a movement which is dangerous because in unskilled hands it uses techniques which ought only to be used in skilled hands and because it exploits the fear and anxiety of the mentally unstable.” She called it “dangerous to their mental health” and commented that the NAMH had received “over a long period, a great many letters from families who have turned to Scientology, and we feel that we’ve got enough evidence to say that they are harming the situation.”

Gaiman claimed that the NAMH had been lobbying against Scientology since at least 1960 and had been seeking to “wipe us out.” He cited evidence of cooperation between the UK NAMH and its South African counterpart, and claimed that “the campaign against us was coordinated through the good offices of the [World Federation of Mental Health]. This has never been denied.” He asserted that Scientology’s 1968 troubles in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Europe and South Africa were “planned” as a response to Scientology “expanding right across the Western world at a pace that could not be ignored.”

Gaiman’s reference to the World Federation of Mental Health (WFMH) highlighted what Scientology saw as the bigger picture. Hubbard had dubbed the WFMH as “SMERSH,” a name borrowed from Ian Fleming’s James Bond books. He described it without any apparent sense of irony as “a world takeover type group, full of preposterous plans,” responsible for “probably the most sinister and bizarre conspiracy against man in all his centuries.”

From 1968 onwards he carried out a systematic campaign against the WFMH that involved burglaries of its offices in Geneva and Edinburgh, and attempts to sabotage its annual conference. When the WFMH opened its Edinburgh office, Hubbard wrote to the British police advising them to arrest its members and those of the NAMH for “statute crimes.” He suggested that the police should call in the military to deal with the WFMH “as they are well trained in purely intelligence matters.” Needless to say, he was ignored and no tanks appeared outside the WFMH and NAMH’s offices.

Scientology’s publication Freedom led the public relations battle against the WFMH and NAMH. It depicted psychiatrists as cartoon skeletons, torturing their patients and with hands dripping with blood. The NAMH had “a huge, steel, walk-in basement safe,” claimed an anonymous Freedom writer, “which contains the personal secrets of English politicians and which are used by psychiatrists.” One issue presented an “Anti-Scientology Organisation Chart” which portrayed the NAMH as the UK arm of an “Attempted World Empire of Psychiatry,” presided over by the WFMH.

The late 1960s were a difficult period for the mental health profession in Britain. A series of scandals in mental hospitals prompted controversy and widespread calls for reforms. Scientology took advantage of this by creating a front group in 1968 called the Association for Health Development and Aid (AHDA). It sold memberships and campaigned for improved medical facilities in mental hospitals. After the AHDA was accused of fraudulently asking for charitable donations — it was not a registered charity — it reportedly returned membership fees to complainants. Perhaps inevitably, Scientology blamed the NAMH for the ADHA’s public relations problems.

Scientology repeatedly accused the NAMH of conspiring to destroy it and subvert society. The NAMH’s files contain no evidence to suggest that it was conspiring against Scientology, nor do they give any indication that it discussed Scientology with the WFMH. However, it did pass on some complaints from members of the public to the British Ministry of Health and communicated with mental health organisations in some other countries, notably South Africa and Australia, in response to inquiries about Scientology. Its role seems to have been more one of exchanging information than trying to advocate any particular measures relating to Scientology.

The Scientologists nonetheless continued to blame the NAMH for the restrictions introduced by the British government in July 1968, though there is no evidence from declassified files that it was involved in any policy discussions with the government. On 11 December 1968, a Scientology delegation descended on the NAMH’s London offices accompanied by a gaggle of newspaper reporters. They demanded to speak with the NAMH’s ‘Board of Directors’ but were told that there was no such body and that nobody from the NAMH’s leadership was in the building at the time. The Scientologists exited in a flurry of publicity, leaving behind a list of highly leading questions about the NAMH’s supposed role in the government’s restrictions. Not surprisingly, the NAMH chose not to respond.

Gaiman soon afterwards resorted to taunting the NAMH over the disruption caused by Scientology’s campaign. In February 1969 he wrote to the NAMH’s press office to tell it: “Dear Opposite Number. How does it feel to be hit? The public sentiment against psychiatry has been bad for years. Lately it has worsened. I have a good idea that it will get much, much worse. Raping women patients, murdering inmates, castrating men, committing without real process of law – the psychiatrist has been a very bad boy.”

Scientology’s war of words was followed by an ambitious plan to infiltrate and take over the NAMH. As Gaiman put it, “we shall, if we have to, take over the field of mental health health and reform it. And we will achieve that purely by winning in the marketplace of ideas.” Events were to show, however, that the GO had no intention of limiting its competition to just “the marketplace of ideas.”

In September-October 1969, the usual ten to twelve applications for membership received each month by the NAMH suddenly shot up to 227. Many of the applications bore date stamps from the post office in East Grinstead, where Scientology had its UK headquarters, or the post office nearest to Scientology’s org at Tottenham Court Road in London. The NAMH believed that most of the new applicants, who numbered over 300 by the time of its annual general meeting on 12 November, were Scientologists. It was a classic case of entryism — a small but highly organised faction attempting to seize control of a larger organisation.

The sudden influx would have made the Scientologists a very substantial and perhaps decisive voting block within the NAMH. The organisation had around 2,000 members but only around fifty usually attended its annual general meetings where leadership elections and organisational policies were conducted and agreed. Had the Scientologists attended the NAMH en masse, they would have been able to swamp the association’s existing members and drive through whatever changes they wanted.

The Scientologists sent two resolutions for debate which strongly criticised the NAMH and called for radical changes to psychiatry. They also demanded that the organisation ally itself with outside groups promoting mental health reforms — an obvious reference to the Church of Scientology. Even more audaciously, two Scientologists nominated Gaiman himself as a candidate for the chairmanship of the NAMH’s executive council. Other Scientologists were nominated by their fellows for the positions of vice-chairman, treasurer and six seats on the council. Gaiman’s nomination attracted a huge amount of press interest, as intended.

Hubbard, who was closely involved behind the scenes, reacted with glee to the furore. He announced to Scientologists that they were now “fighting on enemy terrain… inside his National Association of Mental Health. We are kicking him in the teeth.”

The NAMH invoked emergency measures to freeze memberships until after its AGM. It also sent letters to all those who had joined in the last year asking for their resignation, arguing that the goals of Scientology were incompatible with those of the NAMH. The Scientologists promptly sued, demanding that the courts uphold their positions as legitimate members of the NAMH, and forced a nine-month delay in its planned elections. Outside the hall where the NAMH was holding its AGM, two hundred Scientologists paraded with banners bearing slogans such as “People are Precious” and “Mental Patients Have Rights Too.”

Hubbard blamed the NAMH for refusing to surrender to Scientology, telling the GO that the NAMH’s refusal to “parley” showed that they “have some other target in mind they dare not disclose” and had thus committed themselves to further conflict. He claimed that the NAMH had shown by their refusal that they were acting like “troops who must fight to the bitter end” on the orders of “a command centre or command line.” He presumably believed the WFMH was behind its resistance to Scientology — a link for which no evidence can be found in the NAMH’s files. Comparing the GO’s effort to a counter-insurgency campaign, Hubbard urged them not to let the NAMH “relax or regroup. Keep a rout going by continual attack using old and new angles.”

Gaiman and Balniel submitted duelling affidavits, with the former protesting Scientologists’ rights under ‘natural justice’ and highlighting their sincere interest in reforming mental health care. Balniel pointed out that Scientology was currently engaged in two libel actions against the NAMH and highlighted its ongoing campaign against psychiatry, including the demonstrations against the NAMH. Crucially, he was able to point to statements from existing NAMH members who were horrified at the prospect of a Scientology takeover, citing them as evidence of the damage that the NAMH would suffer and was arguably already suffering as a result of the apparent takeover bid.

The High Court ruled in favour of the NAMH, upholding its decision to expel the new Scientologist members. However, the legal battle cost the NAMH £8,000 and put a heavy strain on its finances and staff. This was entirely consistent with Hubbard’s dictum to bankrupt ‘enemies’ through costly litigation.

Hubbard was delighted with the outcome and wrote to Gaiman to congratulate him on his “splendid NAMH ‘election’ caper. It was brilliantly conceived and executed.” As a result, Hubbard wrote, Gaiman had established that the NAMH was “a private society, not national govt” and that they were “vulnerable to attack.” Scientology had caused their public image to “suffer badly” and, in Hubbard’s view, “their own membership is not loyal and is susceptible to being swayed, I am sure.”

The campaign against the NAMH continued for several years after the “election caper.” It is very likely that the GO had an operative inside the organisation from at least 1970. After Russell Barton, a prominent psychiatrist, shared a draft manuscript of Paulette Cooper’s book The Scandal of Scientology with Edith Morgan of the NAMH, it somehow found its way to the Scientologists.

Barton sent an urgent inquiry to Morgan in July 1970 to inform her that Stephen Bird, a Scientologist lawyer in East Grinstead, had written to her in New York to say that “a psychiatrist has passed on details” of her manuscript. Cooper was very upset and asked if Barton there was a ’spy’ or ‘5th Columnist’ employed in your office.” Barton wondered, “How could Mr. Bird & Mr. Gaiman have found out?”

Further evidence of infiltration emerged in May 1972, when NAMH members received an anonymous typed letter headed “Reform Association for Mental Health” and purporting to be from an ex-member of the NAMH’s staff. The NAMH’s chairman and vice-chairman wrote to the membership denouncing the letter, calling its claims “contemptible and … designed to induce members of the association to distrust the staff and the staff to distrust one another.” It was sent to all individuals on the NAMH’s 1970 mailing list.

As the NAMH acknowledged in a follow-up letter to its members, “we have to face the fact, however, that information from the Association’s files is consistently leaked from within the office to outside people whose object is to attack the Association. The text of the anonymous document which you have received is evidence of this betrayal.” Patrons of the NAMH also received forged letters “of an offensive kind” carrying faked signatures of its secretary and other leading figures.

Hubbard developed a particular obsession with the NAMH’s general secretary, Mary Appleby. She was a long-serving figure in the association, working as a director between 1951 and 1974, and played a key role in its development. Hubbard declared her to be a “Nazi pure and simple” and claimed that she was the “central handler” of the global anti-Scientology conspiracy: “It is she who writes and phones her contacts to start attacks on Scientology.”

Her uncle was Sir Otto Niemeyer “of the World Bank,” Hubbard wrote, therefore his 1965 hypothesis that the World Bank was the secret funder of the conspiracy was “totally correct.” (In fact, Niemeyer was a director of the Bank for International Settlements, a completely different institution — though Hubbard apparently did not realise this.) The NAMH’s files contain no evidence that Appleby was organising attacks on Scientology.

Despite all of Scientology’s efforts, not only did the NAMH not go out of business, but the attempted takeover brought about a new lease of life for the organisation. Its resources had been drained by the battle with the Scientologists. It was forced to launch a new fundraising campaign under the name of MIND. This proved highly successful and prompted a far-reaching makeover for the NAMH. It rebranded itself under the MIND brand and became much more active in lobbying and support activities.

Mind, as it is now known, is now a common sight on British high streets, with more than 130 charity shops across the UK. Far from being destroyed by Scientology, the shock of the attack jolted it into a transformation that made it a much stronger and more successful organisation. Scientology, by contrast, now has only nine outlets across the UK and national census results have found fewer Scientologists than self-proclaimed Jedi Knights.

— Chris Owen

——————–

The Underground Bunker’s official position regarding presidential candidate Marianne Williamson

She’s an idiot.

——————–

Scientology’s celebrities, ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and more!

We’ve been building landing pages about David Miscavige’s favorite playthings, including celebrities and ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and we’re hoping you’ll join in and help us gather as much information as we can about them. Head on over and help us with links and photos and comments.

Scientology’s celebrities, from A to Z! Find your favorite Hubbardite celeb at this index page — or suggest someone to add to the list!

Scientology’s ‘Ideal Orgs,’ from one end of the planet to the other! Help us build up pages about each these worldwide locations!

Scientology’s sneaky front groups, spreading the good news about L. Ron Hubbard while pretending to benefit society!

Scientology Lit: Books reviewed or excerpted in our weekly series. How many have you read?

——————–

THE WHOLE TRACK

[ONE year ago] The two-wheeled spy who loves Blighty: An action report

[TWO years ago] ‘Going Clear’ author Lawrence Wright celebrates a milestone with a different kind of keyboard

[THREE years ago] Scientology appeals $1 million loss to Florida supreme court, and Ken Dandar gets canny

[FOUR years ago] Scientology’s Freedom magazine congratulates itself for going ‘Ideal’

[FIVE years ago] Sunday Funnies: More Scientology fliers than you can shake a stick at

[SIX years ago] Scientology’s Crumbling: Can Gerry Armstrong Begin to Think of Crossing the Border?

[SEVEN years ago] Mimi Faust’s Mother, Olaiya Odufunke: Her Life in Scientology’s Secret Service

[EIGHT years ago] Scientology Uses Its Movie Stars to Woo Politicians, Says Former Top Exec (OR: Tom Cruise Loves Coconut Cake!)

——————–

Bernie Headley has not seen his daughter Stephanie in 5,527 days.

Valerie Haney has not seen her mother Lynne in 1,656 days.

Katrina Reyes has not seen her mother Yelena in 2,160 days

Sylvia Wagner DeWall has not seen her brother Randy in 1,680 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his grandson Leo in 700 days.

Geoff Levin has not seen his son Collin and daughter Savannah in 591 days.

Christie Collbran has not seen her mother Liz King in 3,898 days.

Clarissa Adams has not seen her parents Walter and Irmin Huber in 1,766 days.

Carol Nyburg has not seen her daughter Nancy in 2,540 days.

Jamie Sorrentini Lugli has not seen her father Irving in 3,314 days.

Quailynn McDaniel has not seen her brother Sean in 2,660 days.

Dylan Gill has not seen his father Russell in 11,226 days.

Melissa Paris has not seen her father Jean-Francois in 7,145 days.

Valeska Paris has not seen her brother Raphael in 3,313 days.

Mirriam Francis has not seen her brother Ben in 2,894 days.

Claudio and Renata Lugli have not seen their son Flavio in 3,155 days.

Sara Goldberg has not seen her daughter Ashley in 2,194 days.

Lori Hodgson has not seen her son Jeremy and daughter Jessica in 1,906 days.

Marie Bilheimer has not seen her mother June in 1,432 days.

Joe Reaiche has not seen his daughter Alanna Masterson in 5,521 days

Derek Bloch has not seen his father Darren in 2,661 days.

Cindy Plahuta has not seen her daughter Kara in 2,981 days.

Roger Weller has not seen his daughter Alyssa in 7,837 days.

Claire Headley has not seen her mother Gen in 2,956 days.

Ramana Dienes-Browning has not seen her mother Jancis in 1,311 days.

Mike Rinder has not seen his son Benjamin and daughter Taryn in 5,614 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his daughter Spring in 1,720 days.

Skip Young has not seen his daughters Megan and Alexis in 2,122 days.

Mary Kahn has not seen her son Sammy in 1,994 days.

Lois Reisdorf has not seen her son Craig in 1,577 days.

Phil and Willie Jones have not seen their son Mike and daughter Emily in 2,072 days.

Mary Jane Sterne has not seen her daughter Samantha in 2,326 days.

Kate Bornstein has not seen her daughter Jessica in 13,435 days.

——————–

Posted by Tony Ortega on August 3, 2019 at 07:00

Posted by Tony Ortega on August 3, 2019 at 07:00

E-mail tips to tonyo94 AT gmail DOT com or follow us on Twitter. We also post updates at our Facebook author page. After every new story we send out an alert to our e-mail list and our FB page.

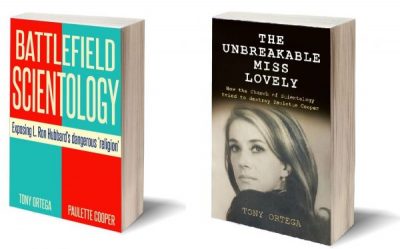

Our new book with Paulette Cooper, Battlefield Scientology: Exposing L. Ron Hubbard’s dangerous ‘religion’ is now on sale at Amazon in paperback and Kindle formats. Our book about Paulette, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology tried to destroy Paulette Cooper, is on sale at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook versions. We’ve posted photographs of Paulette and scenes from her life at a separate location. Reader Sookie put together a complete index. More information can also be found at the book’s dedicated page.

The Best of the Underground Bunker, 1995-2018 Just starting out here? We’ve picked out the most important stories we’ve covered here at the Underground Bunker (2012-2018), The Village Voice (2008-2012), New Times Los Angeles (1999-2002) and the Phoenix New Times (1995-1999)

Other links: BLOGGING DIANETICS: Reading Scientology’s founding text cover to cover | UP THE BRIDGE: Claire Headley and Bruce Hines train us as Scientologists | GETTING OUR ETHICS IN: Jefferson Hawkins explains Scientology’s system of justice | SCIENTOLOGY MYTHBUSTING: Historian Jon Atack discusses key Scientology concepts | Shelly Miscavige, ten years gone | The Lisa McPherson story told in real time | The Cathriona White stories | The Leah Remini ‘Knowledge Reports’ | Hear audio of a Scientology excommunication | Scientology’s little day care of horrors | Whatever happened to Steve Fishman? | Felony charges for Scientology’s drug rehab scam | Why Scientology digs bomb-proof vaults in the desert | PZ Myers reads L. Ron Hubbard’s “A History of Man” | Scientology’s Master Spies | The mystery of the richest Scientologist and his wayward sons | Scientology’s shocking mistreatment of the mentally ill | The Underground Bunker’s Official Theme Song | The Underground Bunker FAQ

Watch our short videos that explain Scientology’s controversies in three minutes or less…

Check your whale level at our dedicated page for status updates, or join us at the Underground Bunker’s Facebook discussion group for more frivolity.

Our non-Scientology stories: Robert Burnham Jr., the man who inscribed the universe | Notorious alt-right inspiration Kevin MacDonald and his theories about Jewish DNA | The selling of the “Phoenix Lights” | Astronomer Harlow Shapley‘s FBI file | Sex, spies, and local TV news | Battling Babe-Hounds: Ross Jeffries v. R. Don Steele