South Africa is a country of extraordinary contrasts: Fertile savannahs and teeming cities, immense wealth and terrible poverty, multiracial idealism and ethnic violence. It’s also a place of striking contrasts in Scientology’s history. In the past few weeks, I’ve been traveling in this vast country and consulting state archives to piece together the story of Scientology in South Africa before the end of apartheid in 1990. They reveal a picture of how Scientology enthusiastically supported South Africa’s apartheid regime while walking a fine line in opposing the government’s favourable views towards psychiatry.

The decades-long freedom struggle of South Africa’s non-white majority gained attention and support from across the world. It’s easy now to forget, though, that many in the West supported the apartheid government as an ally against communism, or – all too often – out of simple racism. Scientology was no exception.

Apartheid might have seemed like a challenge to Scientology’s ideology. After all, L. Ron Hubbard had posited that we are all “thetans” – immortal beings temporarily housed in physical bodies. Skin colour, race, gender and physical age should have been irrelevant considerations. Yet for South African Scientologists, and Hubbard himself, race and politics were defining issues.

Scientology had an early start in South Africa. Dianetics had spread there on a small scale in the early 1950s, likely transmitted by South Africans who had encountered it in the UK or America. Scientology was brought there in 1954 by Albert and Jean Low, a newly-married Canadian-British couple. They had decided to join Hubbard in London for a nine-month evening course in lieu of a conventional honeymoon. While there, they were invited to set up a Scientology training center in Johannesburg by two South Africans attending the course.

Hubbard was eager to sponsor the project. He sent the Lows to South Africa in March 1954 to establish a South African branch of the Hubbard Association of Scientologists International (HASI), later renamed the Hubbard Scientology Organisation in South Africa. It proved hugely profitable.

Scientology expanded rapidly across South Africa, establishing further orgs in Durban, Cape Town, and Port Elizabeth by 1962. Satellite Scientology orgs were also established across the border in white-ruled Rhodesia. Graduates of the South African Scientology orgs later played very senior roles in Scientology. Jane Kember, a Kenyan-born British citizen, performed outstandingly in the Durban org and was personally selected by Hubbard to head his newly-formed Guardian’s Office in 1966. A Rhodesian Scientologist, Charles Parselle, worked alongside Kember as Scientology’s head of legal affairs from 1966 to 1983.

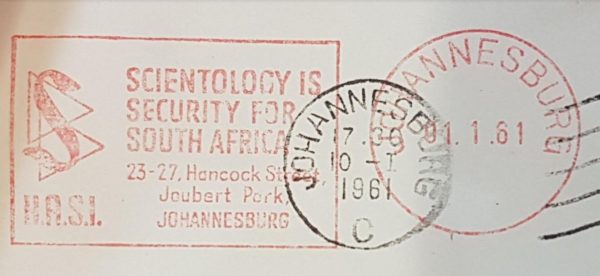

Despite Hubbard’s ostensibly colour-blind teachings, racial domination lay at the heart of South African Scientology in the 1950s and 1960s. The HASI envisaged white Scientologists using Hubbard’s teachings to dominate the country’s oppressed black majority, as the only way of ensuring a stable future for South Africa. Indeed, Scientology promoted itself under the slogan, “Scientology is Security for South Africa.”

A 1955 article in the South African HASI’s Ability magazine declared that only Scientology could solve “the native problem.” It predicted that “when we can get the white people properly straightened out this problem will be nine-tenths solved, evolution and mass processing will then settle the rest.” The Scientology vision for South Africa’s blacks was that they would be “happy working with their hands for understanding employers” who, it hardly needed to be said, would all be whites.

Hubbard clearly had no problems with the idea that Africans were congenitally incapable of governing themselves. In his original 1950 book on Dianetics, he wrote that “the Zulu is only outside the bars of a madhouse because there are no madhouses provided by his tribe.” Similarly, he wrote in Fundamentals of Thought (1956) that “the African tribesman, with his complete contempt for truth and his emphasis on brutality and savagery for others but not himself, is a no-civilisation.”

He told one of his most prominent followers, John McMaster, that black people were so stupid that they did not register on an E-meter. He also informed his Rhodesian followers that black Africans, whom he pejoratively called “batongas,” would not be allowed into Scientology because their IQ was too low.

This was not mere rhetoric. A 1968 November letter sent by Jan Lacey, Scientology’s PR chief for Africa, informed the Interior Minister that because Scientology “fully supports the laws of the Government of South Africa”, i.e. apartheid, “we do not offer services to Africans.” Contemporary photographs from the Johannesburg org show a stark racial division between the all-white Scientology staff and the all-black contingent of cooks, typists, cleaners and other similar support roles.

Hubbard saw southern Africa as a refuge from nuclear war or a communist takeover in the northern hemisphere. He declared that “South Africa and Australia may well be the only civilized countries that will survive a coming atomic war. Thus South Africa has a responsibility to keep civilisation alive and a population free of ‘people’s dictatorships’.” It could also be a refuge for Scientology if its activities were curtailed by hostile governments elsewhere.

This prospect was threatened by an upsurge in protests from South Africa’s black population over the country’s increasingly repressive apartheid laws. They culminated in the 21 March 1960 massacre of 69 black demonstrators in the township of Sharpeville. Nine days later, the South African government declared a nationwide state of emergency.

On the same day, Hubbard sent South African Scientologists a lengthy despatch on how to use E-meters to interrogate blacks and find “subversives.” Uncooperative suspects could be “made to hold the cans (or can be held while the cans are strapped to the soles or placed under the armpit).”

As this method necessarily implied both coercion and physical restraint, it seems likely that Hubbard intended it to be used by the South African police rather than by Scientologists, who were unlikely to be in a position to used physical force on people. Internal records from Scientology’s Johannesburg org and the South African police show that Scientologists did indeed demonstrate to the police how to use the E-meters as an interrogation tool.

Hubbard advised that by using E-meters to interrogate people involved in a riot or strike:

The end product is the discovery of a terrorist, usually paid, usually a criminal, often trained abroad … Twenty or thirty paid agents provocateurs can keep a whole country in revolt. Clean them up and the riots collapse. Thousands are trained every year in Moscow in the ungentle art of making slave states. Don’t be surprised if you wind up with a white. Revolts kill an awful lot of natives. Only when security has been established can a reform be applied. Use E-Meter “clean hands” to convince people that a population is loyal and that reforms are in order.

He advised the government to put black communities under a state of siege to crush non-violent protests:

The answer to passive resistance is for the government to passive strike against any district from which it occurs. No water, lights, pay, government or service. Simply use the same tactic back. Don’t use guns, cordon the area off and shut off power and water.

It’s not clear how much the attitude of the South African government was shaped by Hubbard’s fawning approach to its leadership – a striking contrast to his highly critical approach to the governments of the US, UK, and Australia, which were notably hostile to Scientology. He put a good deal of personal effort into courting Henrik Verwoerd, the South African Prime Minister who was one of the key architects of apartheid.

It was a sign of how important South Africa was to Hubbard that he spent six months there in 1960-61 – his longest continuous stay in any country other than the US or UK. In September 1960 he bought an ultra-modern house in the posh Johannesburg suburb of Linksfield Ridge, on a hilltop overlooking the city. (The house was reacquired some years ago by Scientology, which has expensively renovated it and turned it into a tourist attraction dedicated to Hubbard.) It was from here that he made repeated efforts to make an ally of Verwoerd’s government.

A few days after the London Sunday Times published an article in October 1960 criticising South Africa’s decision to become a republic, Hubbard wrote to Verwoerd to offer his assistance in swaying the UK’s newspapers to take a more pro-government line. He apologised for being unable to stop the “travesty” of the Sunday Times article but told Verwoerd:

We are doing everything we can to change the complexion of the English language press and in a very few months we hope to have the means of completely altering this public image. Peace with strength can yet save, with your undaunted leadership, South Africa. Meanwhile we sincerely hope that vileness such as that in last week’s Sunday Times does nothing to dismay your dedication.

Verwoerd’s decision to break ties with the UK was due to British and international condemnation of South Africa’s forced relocation of non-white populations – a key apartheid policy. Ethnically mixed urban communities were bulldozed and their inhabitants relocated to distant townships. It was widely regarded as an atrocity, but Hubbard praised it, writing to Verwoerd in November 1960:

Having viewed slum clearance projects in most major cities of the world may I state that you have conceived and created in the Johannesburg townships what is probably the most impressive and adequate resettlement activity in existence. Any criticism of it could only be engaged upon by scoundrels or madmen and I know now your enemies to be both.

On the same date, one of Hubbard’s South African representatives wrote to Verwoerd offering Scientology’s help to defend South Africa in court against a lawsuit over its illegal occupation of what is now Namibia. Hubbard also advised Verwoerd to sue countries imposing sanctions and boycotts over apartheid. The government’s replies are not recorded, but Hubbard’s offers of assistance do not appear to have been taken up.

Scientology’s increasing visibility in South Africa and its aggressive recruitment drives – which included targeting school children – led to the first critical coverage in the South African press in 1961. The South African HASI urged Scientologists to write to government ministers and members of parliament “to demand the end of libel and slander of every friend South Africa has by the foreign owned English language press.” They were told to call for “any solution you can think of to end the effort of the Times and various papers and magazines to paralyse South Africa by Red propaganda.”

This attempted linkage of anti-Scientology commentary with Communist and anti-South African propaganda was a theme that Scientology, and Hubbard himself, would repeatedly emphasize for the rest of the decade. There were certainly plenty of opportunities for Scientology to complain. Its expansion in South Africa met with resistance from local and national mental health and medical authorities, who sought to create a coalition to oppose Scientology. The South African Ministry of Health carried out a preliminary investigation but found no tangible facts requiring official action.

The October 1965 release of the highly critical Anderson Report into Scientology in Australia prompted fresh South African attention on Scientology and led to the Psychological Society of South Africa and local psychiatrists launching an investigation. The HASI responded by announcing that it was investigating the psychiatrists and had already compiled damning dossiers that were in the hands of L. Ron Hubbard.

Once again, though, the government took no action. It argued – not unreasonably – that it could not act solely on the basis of a foreign report. Whatever submission the psychiatrists and psychologists made, which is not recorded in government files, evidently did not convince the government that there was an actionable case against Scientology.

At the same time, John McMaster was continuing his work in his native South Africa to boost Scientology’s political influence. McMaster managed to get the interest of one of South Africa’s leading scientists, Stefan Meiring Naudé, and wrote to Hubbard: “We have now pervaded a vital area in South Africa, and you will have many friends there.”

McMaster reported that a local fixer had arranged an interview with the South African Prime Minister which apparently produced a favourable outcome for Scientology. “You asked for strong Orgs in South Africa,” McMaster informed Hubbard. “You will get them and there will be a friendly reciprocity of flow with the Government.”

The increasing pressure on Scientology worldwide following the Anderson Report prompted Hubbard to embark on one of his most farcical efforts – an attempt to establish a new base for Scientology on the shores of Lake Kariba in Rhodesia. While he was making efforts to build up Scientology there, the South African press published further strong criticism of Hubbard’s movement. This and the Anderson Report evidently soured the South African government’s views towards Scientology, as well as increasing the Rhodesian government’s suspicions.

In May or June 1966, Hubbard sent two confidential letters to Verwoerd complaining that the South African High Commission (embassy) in Rhodesia was reluctant to provide him with a visa to visit South Africa. He consistently sought to portray Scientology as a far-right group allied with the apartheid government.

He put the blame for his problems on the influence of the “Communist-dominated government of the [Australian] state of Victoria [which] objected to our rightist leanings” and the fact that “I have many times helped South Africa and publicly opposed Communism,” including refusing a “$150,000 bribe to further the cause of Communism.” Scientology, he wrote, was listed in the “Communist Registry of Rightist Organisations in the U.S. very high on their list, for early disposal.”

“I know how much trouble South Africa has had with churches,” Hubbard told Verwoerd – referring to the role played by churches in opposing apartheid, which Scientology had conspicuously not done – but, he said, Scientology deserved better as “I have over and over proven our loyalty to the Rightist cause.”

Hubbard appealed to Verwoerd to make the South African press stop criticising Scientology, as such “libel and slander in the press” had preceded “the last twenty Nations taken over by Communism… without a single shot being fired.” “This is not a light and airy game,” he warned Verwoerd. “Our red enemy can be counted upon to make mistakes as he is after all pretty stupid. He would not of course be thorough enough in his planning to realise he was attacking a church. Otherwise he would have chosen some other basis for his attack.”

Hubbard never did get his South African visa and never returned to the country. Instead, shortly afterwards, the Rhodesian government refused to renew his visa for that country and sent him packing back to England. On his return he complained bitterly to Verwoerd in a secret telegram, telling him that a South African-born reporter for the British Daily Mail newspaper “often doubles as a communist agent in London” and had given the Rhodesian government “specially printed ‘news cuttings’” to get Hubbard into trouble.

Verwoerd’s office took Hubbard’s claims seriously enough to ask the Interior, Justice, and Information Ministers to provide more information. Perhaps not surprisingly, they reported back that Hubbard’s claims could not be substantiated and that they had no evidence that “his organization is the target of subversive organizations or that its members are able to detect Communists through the lie detector [E-meter].” No action was taken against the reporter. Nonetheless, Scientology continued appealing through the rest of the decade for the increasingly repressive South African government to extend its crackdown on the press to suppress criticism of Scientology.

Hubbard’s decision in 1967 to declare war on psychiatry worldwide created difficulties for South African Scientology, given the close links between influential psychiatrists – some of whom were members of South Africa’s parliament – and the government. Scientology sought to thread this needle by combining all-out attacks on psychiatry with slavish statements of total loyalty to the apartheid regime.

A Scientology official informed the interior minister in October 1967 that the church was “loyal to the government in power” and “upholds and supports … any and all measures taken by the government to handle those forces which seek to cause internal unrest and plan any overthrow of our fatherland.” In a similar vein, the second African edition of Scientology’s propaganda publication Freedom declared on its front page, “We South African Scientologists care deeply for our country [and] we will not allow her to be subverted by Internationalistic forces. Scientologists are totally loyal to the Government of South Africa.”

Scientology’s South African publications sought to associate psychiatry with communism in the evident hope that the fervently anti-communist government would extend its crackdown to cover psychiatry. Freedom portrayed Scientology’s critics as “Communist infiltrators, working apparently for the good of South Africa, [who] attack Scientology under the pretence that they are protecting South Africans.” The end goal, it claimed, was “a psychopolitical takeover in South Africa.”

Scientology sought fairly explicitly to distance itself from the anti-apartheid movement, tying it to psychiatry and communism. When the World Council of Churches announced that it would step up its campaign against apartheid by funding black liberation movements in southern Africa and disinvesting in corporations doing business with white-ruled African countries, Freedom declared that the church “does not belong to this religious body and is emphatic in its condemnation of terrorism or encouragement thereof.”

In a similar vein, Scientology opposed anti-apartheid student demonstrations that broke out at several English-speaking universities around South Africa in 1969. It sought to persuade the government that psychiatrists were behind the protests. “It is obvious,” the church’s executive council wrote in a telegram to the minister of police, “that the students are being used as dupes in a much larger plan.”

The council asked permission for Scientologists to hold a counter-demonstration against the students of Witwatersrand University with posters carrying quotes such as, “Who is the third party involved in student riots against governments?”, “Attack real violation [sic] of human rights like the atrocities done in the name of mental healing,” and “Attack materialism and not a government with spiritual values.” The council also urged the government to “stop the press using an unwitting minority to destroy the security of South Africa.” However, the minister refused to sanction the planned counter-demonstrations.

The government did not act on Scientology’s demands or claims, and also did not ban it as some psychiatrists had demanded. It did, however, make life more difficult for Scientology by refusing visas to some foreign Scientologists. It also placed some Scientology works on its banned literature list, though it also – bafflingly – censored Robert Kaufman’s highly critical book “Inside Scientology,” perhaps misunderstanding its nature.

Its increasing antagonism likely led Scientology to take a more hostile approach towards the government in the 1970s. The church carried out a high-profile campaign against the appalling conditions inflicted on black people in the state-run but chronically underfunded mental health system. The campaign attracted international attention and forced the government to implement reforms, though it almost certainly increased the government’s hostility towards Scientology.

By the later 1970s, there was no longer much point in Scientology trying to make nice with the South African government. This likely led the Guardian’s Office to make the bold if risky decision to target the government directly to expose abusive mental health practices in state-funded institutions. In 1976, Scientologists reportedly burgled the Ministry of Health, church offices, and the office of the director of a company that ran mental institutions in South Africa. Scientology also shifted to taking an overtly anti-apartheid stance through the 1980s, a decision likely linked to the changing political climate internationally; it was no longer tenable to be a public supporter of apartheid outside South Africa.

Scientology’s history in South Africa prior to the end of apartheid was thus a very mixed one: forthright support of apartheid, opposition to the anti-apartheid movement and overt racial discrimination within the organisation, before a late change of heart when support for apartheid was no longer a politically attractive proposition. Today, Scientology’s “L. Ron Hubbard House” in Johannesburg portrays him as a pioneer of racial equality and a fervent opponent of apartheid. As the files and publications held in South Africa’s archives demonstrate, however, the reality – as usual – was very different.

— Chris Owen

——————–

HowdyCon 2019 in Los Angeles

THURSDAY NIGHT OPPORTUNITY: This year’s HowdyCon is in Los Angeles. People tend to come in starting on Thursday, and that evening we will have a casual get-together at a watering hole. But we also want to point out that Cathy Schenkelberg’s “Squeeze My Cans” will be running at the Hollywood Fringe, and we encourage HowdyCon attendees to see her show on Thursday night, June 20. Tickets and more dates available here.

Friday night June 21 we will be having an event in a theater (like we did on Saturday night last year in Chicago). There will not be a charge to attend this event, but if you want to attend, you need to RSVP with your proprietor at tonyo94 AT gmail.

On Saturday, we are joining forces with Janis Gillham Grady, who is having a reunion in honor of the late Bill Franks. Originally, we thought this event might take place in Riverside, but instead it’s in the Los Angeles area. If you wish to attend the reunion, you will need to RSVP with Janis (janisgrady AT gmail), and there will be a small contribution she’s asking for in order to help cover her costs.

HOTEL: Janis tells us she’s worked out a deal with Hampton Inn and Suites, at 7501 North Glenoaks Blvd, Burbank, (818) 768-1106. We have a $159 nightly rate for June 19 to 22. Note: You need to ask for the “family reunion” special rate.

——————–

Scientology’s celebrities, ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and more!

We’ve been building landing pages about David Miscavige’s favorite playthings, including celebrities and ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and we’re hoping you’ll join in and help us gather as much information as we can about them. Head on over and help us with links and photos and comments.

Scientology’s celebrities, from A to Z! Find your favorite Hubbardite celeb at this index page — or suggest someone to add to the list!

Scientology’s ‘Ideal Orgs,’ from one end of the planet to the other! Help us build up pages about each these worldwide locations!

Scientology’s sneaky front groups, spreading the good news about L. Ron Hubbard while pretending to benefit society!

Scientology Lit: Books reviewed or excerpted in our weekly series. How many have you read?

——————–

THE WHOLE TRACK

[ONE year ago] EXCLUSIVE: The rise and fall of the ‘Pope of Scientology’ — in his own words

[TWO years ago] Designer Rebecca Minkoff’s involvement in a Scientology front is pretty perfectly bad timing

[THREE years ago] Chick Corea’s glib revelation to the New York Times about Scientology’s ‘Maiden Voyage’

[FOUR years ago] Jon Atack: The ‘Getting Clear’ conference and L. Ron Hubbard’s lies about his life

[FIVE years ago] Where is Scientology keeping Samantha Sterne?

[SIX years ago] Dianetics Has No Patience for ESP or Telepathy — That’s Pseudoscience!

[EIGHT years ago] Scientology: Christmas Comes Early with TWO New Books on Hubbard’s Wacky Cabal

——————–

Bernie Headley has not seen his daughter Stephanie in 5,469 days.

Valerie Haney has not seen her mother Lynne in 1,598 days.

Katrina Reyes has not seen her mother Yelena in 2,102 days

Sylvia Wagner DeWall has not seen her brother Randy in 1,622 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his grandson Leo in 642 days.

Geoff Levin has not seen his son Collin and daughter Savannah in 533 days.

Christie Collbran has not seen her mother Liz King in 3,840 days.

Clarissa Adams has not seen her parents Walter and Irmin Huber in 1,708 days.

Carol Nyburg has not seen her daughter Nancy in 2,482 days.

Jamie Sorrentini Lugli has not seen her father Irving in 3,256 days.

Quailynn McDaniel has not seen her brother Sean in 2,602 days.

Dylan Gill has not seen his father Russell in 11,168 days.

Melissa Paris has not seen her father Jean-Francois in 7,088 days.

Valeska Paris has not seen her brother Raphael in 3,255 days.

Mirriam Francis has not seen her brother Ben in 2,836 days.

Claudio and Renata Lugli have not seen their son Flavio in 3,097 days.

Sara Goldberg has not seen her daughter Ashley in 2,136 days.

Lori Hodgson has not seen her son Jeremy and daughter Jessica in 1,848 days.

Marie Bilheimer has not seen her mother June in 1,374 days.

Joe Reaiche has not seen his daughter Alanna Masterson in 5,463 days

Derek Bloch has not seen his father Darren in 2,603 days.

Cindy Plahuta has not seen her daughter Kara in 2,923 days.

Roger Weller has not seen his daughter Alyssa in 7,779 days.

Claire Headley has not seen her mother Gen in 2,898 days.

Ramana Dienes-Browning has not seen her mother Jancis in 1,253 days.

Mike Rinder has not seen his son Benjamin and daughter Taryn in 5,556 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his daughter Spring in 1,662 days.

Skip Young has not seen his daughters Megan and Alexis in 2,064 days.

Mary Kahn has not seen her son Sammy in 1,936 days.

Lois Reisdorf has not seen her son Craig in 1,519 days.

Phil and Willie Jones have not seen their son Mike and daughter Emily in 2,014 days.

Mary Jane Sterne has not seen her daughter Samantha in 2,268 days.

Kate Bornstein has not seen her daughter Jessica in 13,377 days.

——————–

Posted by Tony Ortega on June 6, 2019 at 07:00

Posted by Tony Ortega on June 6, 2019 at 07:00

E-mail tips to tonyo94 AT gmail DOT com or follow us on Twitter. We also post updates at our Facebook author page. After every new story we send out an alert to our e-mail list and our FB page.

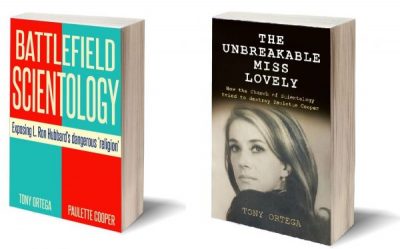

Our new book with Paulette Cooper, Battlefield Scientology: Exposing L. Ron Hubbard’s dangerous ‘religion’ is now on sale at Amazon in paperback and Kindle formats. Our book about Paulette, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology tried to destroy Paulette Cooper, is on sale at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook versions. We’ve posted photographs of Paulette and scenes from her life at a separate location. Reader Sookie put together a complete index. More information can also be found at the book’s dedicated page.

The Best of the Underground Bunker, 1995-2018 Just starting out here? We’ve picked out the most important stories we’ve covered here at the Underground Bunker (2012-2018), The Village Voice (2008-2012), New Times Los Angeles (1999-2002) and the Phoenix New Times (1995-1999)

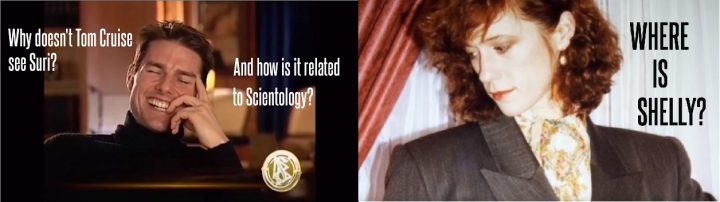

Other links: BLOGGING DIANETICS: Reading Scientology’s founding text cover to cover | UP THE BRIDGE: Claire Headley and Bruce Hines train us as Scientologists | GETTING OUR ETHICS IN: Jefferson Hawkins explains Scientology’s system of justice | SCIENTOLOGY MYTHBUSTING: Historian Jon Atack discusses key Scientology concepts | Shelly Miscavige, ten years gone | The Lisa McPherson story told in real time | The Cathriona White stories | The Leah Remini ‘Knowledge Reports’ | Hear audio of a Scientology excommunication | Scientology’s little day care of horrors | Whatever happened to Steve Fishman? | Felony charges for Scientology’s drug rehab scam | Why Scientology digs bomb-proof vaults in the desert | PZ Myers reads L. Ron Hubbard’s “A History of Man” | Scientology’s Master Spies | The mystery of the richest Scientologist and his wayward sons | Scientology’s shocking mistreatment of the mentally ill | The Underground Bunker’s Official Theme Song | The Underground Bunker FAQ

Watch our short videos that explain Scientology’s controversies in three minutes or less…

Check your whale level at our dedicated page for status updates, or join us at the Underground Bunker’s Facebook discussion group for more frivolity.

Our non-Scientology stories: Robert Burnham Jr., the man who inscribed the universe | Notorious alt-right inspiration Kevin MacDonald and his theories about Jewish DNA | The selling of the “Phoenix Lights” | Astronomer Harlow Shapley‘s FBI file | Sex, spies, and local TV news | Battling Babe-Hounds: Ross Jeffries v. R. Don Steele