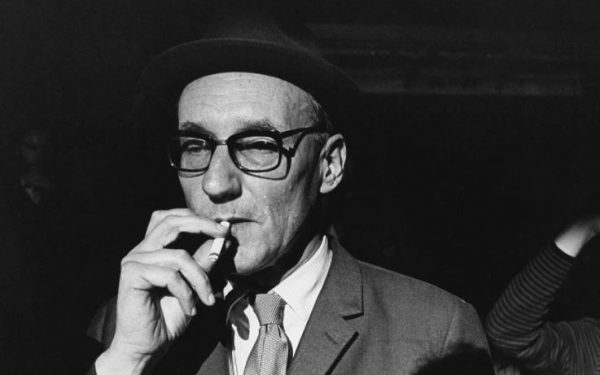

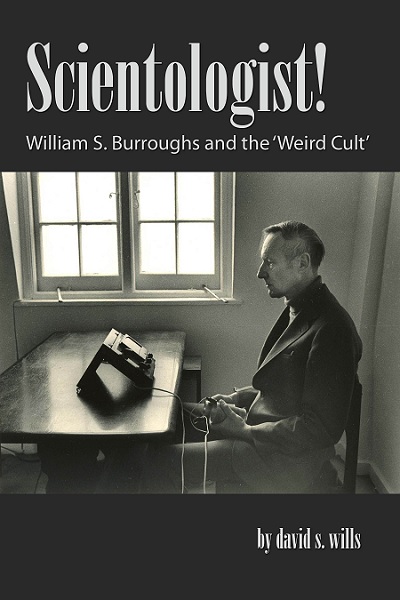

In 2013, we interviewed author David Wills about his book on William Burroughs, Scientologist! William S. Burroughs and the ‘weird cult’. He argued that Burroughs biographers tended to play down (or merely not understand) how deeply into Scientology Burroughs had been before famously falling away from it in scathing testimonials. We thought he put together a pretty compelling picture about Burroughs’ involvement in Scientology, which happened from 1959 to about 1969. In this excerpt from his book which Wills has generously agreed to share, we’ve taken a portion of the chapter when Burroughs was at his most enthusiastic, while at Saint Hill Manor in 1968.

Saint Hill Manor was purchased by L. Ron Hubbard in 1959 as a training center for Scientologists. The year Burroughs enrolled for his first training course, the brochure fawned over the building’s impressive setting and history. It is written with Hubbard’s unmistakably trite and self-aggrandizing phrasing, not to mention his fondness for the word “free” and its derivatives:

Throughout the history of Man, one reads of Man’s continual efforts to free himself from bondage, slavery and ignorance… Scientology has found the answers and the Road to Total Freedom.

He goes on to mention England’s clichéd “green fields” and “rolling hills,” and even is as audacious as to suggest a warm and sunny climate, thanks to the “Gulf stream [blowing] across the Atlantic from the Caribbean.” He talks about the country’s “10,000 years” of history with “many major events.” However,

These events don’t compare, in any way, to the current historic events or the contribution being made to mankind at Saint Hill now… The ultimate developments of Scientology by L. Ron Hubbard at Saint Hill is an achievement without equal in the annals of history, and is indeed history in the making.

The brochure is illustrated with photos of young men and women (mostly women) in ridiculous poses, smiling and laughing, reminiscent of boxes from old board games. Again, Hubbard’s overblown language comes clearly across in the captions: “laugh gorgeously,” “graceful,” “serene,” and “delightful.” Finally, the brochure concludes by claiming: “Saint Hill is a shining beacon for all to reach for in a world that is dark through ignorance and misery.”

If this sounds a little over-the-top, it is nothing compared to the essay that Burroughs produced after enrolling at Saint Hill in the Hubbard Trained Scientologist Course. It was printed in the January edition of Mayfair, and was titled “Scientology Revisited.” The tagline would have surprised anyone who had read his previous essay, which read more or less as an advertisement for the organization:

I had a number of misconceptions about Scientology – the lurid expectations of a secret and sinister cult. But, as I learned more, I had a final conviction that Scientology does point out a whole new way of looking at this universe.

At the editor’s admission, there were probably few customers who actually took the time to read Burroughs’ essays, or indeed any of the text printed in the magazine. Mayfair was pornographic and its “readers” largely had one intention when opening it. But anyone who had read [Burroughs’ previous essay] “The Engram Theory” would be surprised to know that Burroughs harbored any negative thoughts about Hubbard or his Church. Indeed, it is odd to see Burroughs even use the words “sinister” or “cult,” but perhaps that was just a way of grabbing attention. At the time, public opinion regarding Scientology was on a severe downwards slope, and having been thoroughly impressed by his visits, by the literature, and by a brief time spent enrolled in a training course, Burroughs was ready to take on the international media by arguing – without the use of cut-ups – that there was nothing objectionable about Hubbard or Scientology.

The essay opens with yet more silliness. He states that its purpose is to correct errors in “The Engram Theory,” and points out that it was intended simply to act as an overview of the religion – with Burroughs suggesting that he had expected to find something awful, but that he had managed to offer a “critical approach to the literature of Scientology.” There are less ridiculous phrases attributed to the naked women throughout the magazine. It becomes apparent that the point of this essay is simply to erase any doubts he had left in the minds of his readers that Scientology is the most important system of belief in the world, and that this essay was going to be even less “critical” than the first.

Had he not already lost the respect of his readers, Burroughs quickly moves into heaping praise upon L. Ron Hubbard as a writer, saying that although “he does sound rather like a visitor from outer space who has taken a refresher course in how to address the natives on their own level,” his writing is nonetheless “clear and precise” and that he is “more a technician and an organizer than an artist.”

Not satisfied with throwing his literary credentials out the window, he moves quickly into his only new complaint: that the name Scientology opens the organization to mockery. He paints the scene at a snooty literary dinner party, where the guests mock the oddness of the name and suggest it is just “another cult” from Southern California, owned and operated by hippies. But once again, Burroughs draws upon his old favorite, Korzybski, who once famously pointed at a chair and claimed it was anything but a chair. “Whatever Scientology may be it is not the label the word ‘Scientology.’ ” In the end, it is the people who mock Scientology, in Burroughs’ mind, who are foolish.

Soon he’s correcting himself by removing any doubt over the problems and misuses of Hubbard’s discoveries:

What I said in Bulletin 2 relative to the misuses of Scientology in the wrong hands is all too accurate. The best insurance against the misuse of Scientology is afforded by the open dissemination of information, processing and training offered at 37 Fitzroy Street, London and Saint Hill, East Grinstead, Sussex. There is nothing secret about Scientology, no talk of initiates, secret doctrines or hidden knowledge.

He continues by suggesting that there are secret organizations around the world out to control the human race by stealing Scientology’s methods, and that all negative publicity aimed at Hubbard is pure propaganda by these same forces. He says that “facts” don’t matter because the media will always lie to cover for the powers that wish to do evil.

The media, whose anti-Scientology reports Burroughs had previously believed to be accurate, remains the focus of his next tirade:

An accusation brought against Scientology in the press is of course ‘brain washing,’ the implication being that anything which alters thinking is bad by nature. It is of course understandable that those individuals who profit from keeping the public in ignorance and degradation do not want their thinking altered in any way and most particularly not in the direction of freedom from past conditioning which they have carefully installed.

After a few weeks of studying Scientology, Burroughs himself appears somewhat brainwashed, and can’t see the irony in his argument.

It is amazing just how enthusiastic he sounds in this essay, not only for the engram theory and the E-meter, but for every aspect of Scientology, including Hubbard. Despite earlier reservations, and later criticism, he appears absolutely won over, and is bent on disavowing his own suggestions that Scientology may be less than perfect, and especially eager to contradict the media’s attacks. He even defends Hubbard’s reputation by saying his “degrees and credentials seem hardly relevant. Dianetics and Scientology are his credentials and he needs no others.” Of course, by this stage Hubbard’s past had already been under intense scrutiny. But such criticisms never stopped Burroughs from defending Reich, and they weren’t about to sway him to the dark side in regards to his new hero.

Having satisfied himself that he had put to the sword any doubts about the brilliance of Scientology, and having cleared his conscience for having questioned it in his November essay, Burroughs moves on to describe his experiences on the training course. But not before listing the address of the center (again), its opening hours, rules, and even the price of the course (a very reasonable thirty pounds per week). He claims that the course will make you smarter, so that you don’t just learn Hubbard’s teachings quickly, but you can improve your ability to learn anything. You can also remove annoying mannerisms, and make yourself more socially adept – something that no doubt would have served Burroughs well as an awkward young man. In a telling turn of phrase, he even claims that Scientology could help people who have been socially “handicapped for years.”

Burroughs goes on to describe the auditing process, and in particular the use of the E-meter. He describes the process in general, before claiming that it is all true – “anyone who undergoes processing” knows that engrams are real and that auditing works. However, Burroughs’ claim to objectivity is again shot when he reveals his own experiences, seemingly by accident, whilst trying to stay out of the story:

There is a moment when the incident is quite clear and then suddenly fades like old film as the needle floats. There is a sort of click in the head when this happens. You can feel the needle float.

By revealing that he underwent auditing and that it seems to have had the same effect he got from drugs or his orgone accumulators, he is giving away probably more than he intended. Again, to him it is proof. Scientology is a matter of facts. But to anyone bringing a critical mind to his descriptions, he sounds like another convert to a cult, drugged and brainwashed by false promises.

In his conclusion, Burroughs weighs up the benefits of Scientology against his own life experiences:

As one who wasted four years and thousands of dollars on psycho-analysis I can testify that Scientology processing administered by a competent professional can do more in five hours than psycho-analysis can do in five years.

He continues by reminding his readers that Scientology is not just a means to erase bad memories and enhance our abilities, but is also an essential element of the fight against mind control through language, and ends by saying that it shares common ideas with Hassan ibn Sabbah – something that surely would have only served to further alienate any of the magazine’s readership.

A less balanced essay there could hardly be, but “Scientology Revisited” is invaluable evidence in uncovering the importance of the religion in Burroughs’ life. Most interestingly, it shows just how impressionable the man was. When he first learned about Scientology from Brion Gysin in Paris, Burroughs was aware of some of the negative sides to the religion, and demonstrated in the following years some minor reservations. Yet the more he studied, the fewer reservations he had. He viewed it first and foremost as a means of freeing himself from systems of control – something of benefit for the whole of humanity. By the end of January 1968, after a few short weeks of auditing, he appears as dedicated as the follower of any cult – and his knee-jerk reaction is to dismiss his own previous doubts, along with the protestations of any naysayers outside the organization. This essay marks the high point of his obsession. For seven years his enthusiasm built to this point, and one doubts any person alive could have successfully remonstrated with him over Scientology’s dark side. This is most likely because Scientology was becoming more than just a weapon in the fight against the word virus, but was becoming a tool for him to heal himself. All his life Burroughs sought such things. He was a deeply scarred human being with a mind full of awful memories and what he perceived as handicaps – his homosexuality and drug addictions. He had sought to fix his problems through therapy, yet evidently Scientology was a quicker and more effective fix. As intelligent as Burroughs was, he was nonetheless fragile, and as wary as he was of being a “mark,” he was so desperate to find a cure for his pains that he would have walked into any trap set just for him. And looking back at his history of beliefs, and his long line of particular problems, no trap was as custom-made for this man as the Church of Scientology.

On his first day at Saint Hill, Burroughs sat in the auditing room and the process started. In Scientology, the communication cycle – with which Burroughs was already familiar because of his prior study – is rigid and follows a pattern that is odd to the outside observer. In material that Burroughs later studied and kept, Hubbard explained: “To add words to the patter is to risk restimulation and it is expressly forbidden to do so.” It is also forbidden for auditors to give any sort of opinion as a response to the preclear: “Above all, don’t be critical of the pc.” The cycle is carefully designed, and is said to have effects similar to hypnosis. It is intense and can produce hallucinations, and supposedly even out-of-body experiences. In Burroughs’ case, the auditor began by posing a series of questions. The preclear in this case is allowed to answer in any way except by leaving his chair, and Burroughs – recounted in an interview with Bill Morgan – appears to have been somewhat provocative in return.

When the auditor asked him what he would say if he met the president, Burroughs replied, “Drug hysteria.” As part of the cycle, the auditor must coax the preclear to elaborate, and Burroughs went on to say that he would ask the president, “What are you trying to do, turn America into a nation of rats? Our pioneer ancestors would piss in their graves.” To the pope, Burroughs claimed he would say, “Sure as shit, they will multiply their assholes into the polluted seas.”

The auditor then ended the session for a break, after which they continued by addressing overts and withholds. The purpose of this session is to explore some more obvious traumas and issues with the preclear. In this case, the subject of Kiki – the boy Burroughs had fallen in love with in Tangier – came up. Burroughs explained that Kiki had died, and began to talk about how he felt. In Scientology, however, it is not important to go into depth about such things, and the auditor pushed Burroughs instead to picture Kiki, going back in his memory to the clothes that Kiki wore. When pushed back into his memories, being able to see and hear and smell things as though they were happening again, Burroughs blacked out. When he woke up, the auditor told him that he’d experienced a “Rock C slam” – in other words, a particularly strong reaction had registered on the E-meter.

Incidents such as the above, which are available to the analytic mind, are known as “secondaries” – and are used to guide auditors to engrams. In the beginning they are powerful and can have effects like Burroughs suffered. But replaying the trauma, guiding the preclear from the beginning of the memory to the end, over and over, is said to render the engram powerless. Sometimes neither the auditor nor the preclear can understand what the problem is, or why it is being released, but in Burroughs’ case he found it immensely therapeutic. For him the phrases that would give a floating needle were mostly “quotes from my own work or someone else.” In one instance he found “hieroglyphics” registered as a floating needle, signaling that an engram had been run. Other release points included the phrase “Why, it’s just an old movie,” a meeting he could barely remember with a man called Lord Montague, the British museum, the phrase “sharp smell of weeds from old Westerns,” and the character of Scobie from Graham Greene’s novel, The Heart of the Matter. Sometimes his words were like cut-ups: “The emerald beginning and end of word.” He didn’t necessarily understand exactly what was going on, but Burroughs was sufficiently relieved of pain that only a short while into his course, he wrote the Mayfair essay “Scientology Revisited.”

During these secondaries, Burroughs noticed that the word “emerald” kept popping up. Twice it marked a release, but he didn’t know why. His auditor told him that this could mean an attachment to a “suppressive person,” or maybe a place or object, and he was told to go through a process called “S&D,” wherein “you simply list items and then check on the E-meter.” Burroughs ran through some obvious possibilities, but then considered that it might be, as the auditor said, “an object.” He suggested the word “emerald,” and got a floating needle. “That’s it,” the auditor said. Burroughs never understood the importance of the word.

From the Hubbard Trained Scientologist Course in January, Burroughs quickly moved on to Auditing then Grade IV Release, Power Processing, and the Solo Audit Course. In all, the courses were intensive and lasted up to eight hours a day, five days a week, and went on for several months. The Solo Audit Course alone took two months of intensive study to complete, and required listening to sixty hours of Hubbard speaking on tape. During this time he lived in a shared house with six or seven other Scientologists, returning to his own apartment only on weekends. Sommerville found him intolerable during this period, as Burroughs attempted to audit everyone around him (including the poet, Harold Norse, who Burroughs claimed reacted with enthusiasm), and went on at length about Scientology. He claimed Burroughs would give him his “Operating Thetan glare,” which deeply disturbed Sommerville.

In his letters to Gysin, Burroughs is somewhat restrained. Gysin was never a member of the Church of Scientology and merely found it interesting, and in his letters over the intervening decade it seems Burroughs is trying to downplay his own enthusiasm, and sometimes to rekindle Gysin’s. Shortly after starting back at Saint Hill in January, he wrote Gysin to say that he had been “reinstated” (as though he’d been thrown out), and then offers a pithy excuse for going back for more:

The fact is that processing has uncovered a lot of extremely useable literary material and dreams now have a new dimension of clarity and narrative continuity. I have already made more than the money put out on stories and material directly attributable to processing. So might as well follow through and see what turns up.

Perhaps referring to this argument, Gysin would later joke that Burroughs was just about the only person to have made more money from Scientology than they had taken from him. Later in his letter, Burroughs talks about viruses, and references Hubbard several times, indicating that his own views were being changed quite substantially since having resumed his Scientology studies. In another letter he repeats the “reinstated” claim and goes on immediately to talk about the number of men on the course. “The whole organization has been inundated with males and we are now in a majority.” He tries to win Gysin over with the number of men around, with claims that the auditing procedure induces a state that brings about naturally spoken cut-ups, and the fact that Balch and Harold Norse had been processed.

At some point during his time at Saint Hill, after finishing up his Power Processing course but prior to being declared clear, Burroughs wrote an essay called “Power.” This essay remains unpublished, however, parts were paraphrased and included in a Scientology magazine over the summer. There is nothing in the essay to suggest that Burroughs had anything but positive thoughts about his experience on the course, and we can assume that he at least knew that other Scientologists would read it, but he does daringly suggest improvements upon the system. It begins by outlining the traditional view of power: nations with armies, police forces, and money. But, he says, these things “come and go and are no more. The power that remains is the power each individual has within himself.” He goes on to explain how the most important force in the universe is a Clear, and finishes up by giving his personal testimony:

This is the power released by power processing. This power is the abilities regained after release from counter forces that have blocked the individual from the use of these abilities. Once regained these powers cannot be taken away from the individual. It is his power. Power processing is release from whole track engrams experienced over thousands of years. That this release can be effected in a few hours demonstrates the point of perfection achieved by Scientology technology. It is not necessary to locate them and run out thousands of such moments any more than we need to excise each individual germ to be cured of an illness. To run each engram would take a lifetime of auditing. The technology pin points a few whole track engrams and clears these on the E-meter. The P.C. knows as well as the auditor when the needle floats. Anyone who experiences power processing knows that he has been released and that he has regained his power that he can now apply to his life and his work.

Whilst studying auditing, Burroughs became interested in the idea of exteriorization – when a person’s spirit, soul, or conscious energy form leaves the body. He produced a cut-up of some Scientology literature regarding this technique, and mixed it with some of his thoughts about using tape recorders. “Ask the preclear to be a foot back of his head,” he says, quoting an early instruction. There is also reference to “pressor beams,” which are a form of concentrated energy, much like a laser, that high-level Scientologists are supposedly able to produce. Burroughs was very interested in lasers at this point, but this is unsurprising as he had always been interested in shifts in time and space.

In another unpublished essay written the following year, Burroughs recalls his time living at Saint Hill as his enthusiasm began to wane under the stress and rigid nature of life there. It begins, “Now to give you an idea of what St. Hill was like in my day.” He describes living with six young Scientologists, including females who “come on with cognitions and embarrassing thinly disguised sexual dreams about Ron like young nuns dreaming of Christ.” Together they would all drive at top speed to get to their classes on time, as punishments were strict. If they were late, they had to wear a grey rag tied around their arm, signifying that they were in a condition of Liability. As if this wasn’t embarrassing enough, they were forbidden from eating lunch, as well as from shaving or washing, during this period of punishment, and to end it they were required to collect signatures to a petition in order to absolve them of their sin.

Despite his years of studying, Burroughs recalled being constantly in fear of failing the E-meter. He compared himself to young women with “high tone arm” and said that “fear stirs in my stomach” whenever he thought of the device. He described his “twin” – the person primarily responsible for auditing him – as “a nice middle-aged woman from California, I would judge she’s buried three husbands $250,000 a coffin.” The supervisors could be particularly harsh, and reduced some of the women to tears. To Burroughs they’d say, “You’re in a condition of danger.” Telling the story years later, Burroughs liked to present the people around him as military types, barking orders, marching preclears about the building, and making them line up.

Indeed, Burroughs was coming to the attention of the authorities. Although his opinions regarding the genius of Hubbard’s ideas were unchanged, his attitude towards being controlled was predictable. He had never been good at obeying rules or doing what he was told, and whilst at Saint Hill he did admirably in fighting his urges to rebel. But he was still subjected to the dreaded Sec Check – a formidable list of questions designed to weed out potentially disruptive students. He claimed that so many students were being dragged into Sec Checks that he was required to perform his in a broom closet with “some grim old biddy.” The first question was: “Do you feel that St. Hill is a safe environment?” Burroughs claims to have replied: “It’s so safe it’s overwhelming gee I never felt like this before you know what I mean like belonging to something big,” whilst later adding, “All this time I felt my self respect slipping away from me and finally completely gone as it were officially removed.” All this was recorded on the E-meter, which was basically a lie detector. Other questions included: “Are you here for any other reason than you say you are?” “Do you have any doubts about Scientology?” and “Do you harbor any unkind thoughts about L. Ron Hubbard?”

This last question posed a problem for Burroughs, who was quickly becoming sickened of the cult of personality around Hubbard, but he supposedly managed to fire off a quick reply that satisfied his interrogators: “Well, I just can’t help being jealous of someone who is so perfect.” In a remarkably short time he had grown to hate the man’s “big fat face,” and although he still respected his ideas, he went home to his apartment at the weekend and fired his air gun at photos of Hubbard he stuck on his wall in a crude attempt at a curse. One time the hammer of his gun snapped back and very nearly broke his thumb, and Burroughs felt that Hubbard had somehow managed to return the curse.

According to the essay, Burroughs viewed himself as an anthropologist attempting to “penetrate a savage tribe… to get the bog medicine he has come for.” His initial exposure to the inside of the religion had convinced him that it was pure and good, but having dug a little deeper, he claimed to despise it and was simply searching for a cure to his own problems before escaping.

Still, one should keep in mind that this essay was written around a year later, and at the time Burroughs appeared utterly captivated by the Church of Scientology. His later references to the time at Saint Hill were far more negative than his notes and letters from the time, indicating that he exaggerated or spun his stories later, when his opinions had soured. While at Saint Hill, he wrote to friends, recommending that they, too, get audited, and although he acknowledges that Hubbard is a poor writer, he pushes his theories on the recipients of his correspondence from Saint Hill. On the Solo Audit Course, he wrote Gysin to say, “I am interested to really learn the subject having already profited professionally.” He clearly had a sincere drive to learn and advance in the religion.

— David S. Wills

——————–

Chris Shelton and Sunny Pereira

Says Chris: “This week, I invited Sunny Pereira (former Sea Org member and highly trained case supervisor), to discuss how Scientology auditing is organized and delivered, including what the case supervisor function is and how very different this is from any normal psycho-therapeutic setup.”

——————–

HowdyCon 2019 in Los Angeles

This year’s HowdyCon is in Los Angeles. People tend to come in starting on Thursday, and that evening we will have a casual get-together at a watering hole. We have something in mind, but for now we’re not giving out information about it.

Friday night we will be having an event in a theater (like we did on Saturday night last year in Chicago). There will not be a charge to attend this event, but if you want to attend, you need to RSVP with your proprietor at tonyo94 AT gmail.

On Saturday, we are joining forces with Janis Gillham Grady, who is having a reunion in honor of the late Bill Franks. Originally, we thought this event might take place in Riverside, but instead it’s in the Los Angeles area. If you wish to attend the reunion, you will need to RSVP with Janis (janisgrady AT gmail), and there will be a small contribution she’s asking for in order to help cover her costs.

HOTEL: Janis tells us she’s worked out a deal with Hampton Inn and Suites, at 7501 North Glenoaks Blvd, Burbank, (818) 768-1106. We have a $159 nightly rate for June 19 to 22.

——————–

Scientology’s celebrities, ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and more!

We’ve been building landing pages about David Miscavige’s favorite playthings, including celebrities and ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and we’re hoping you’ll join in and help us gather as much information as we can about them. Head on over and help us with links and photos and comments.

Scientology’s celebrities, from A to Z! Find your favorite Hubbardite celeb at this index page — or suggest someone to add to the list!

Scientology’s ‘Ideal Orgs,’ from one end of the planet to the other! Help us build up pages about each these worldwide locations!

Scientology’s sneaky front groups, spreading the good news about L. Ron Hubbard while pretending to benefit society!

Scientology Lit: Books reviewed or excerpted in our weekly series. How many have you read?

——————–

THE WHOLE TRACK

[ONE year ago] Scientologists bombarded to attend Hubbard birthday events, and this is our favorite flier

[TWO years ago] As Louis Theroux’s ‘My Scientology Movie’ hits, troubling news of co-star Marty Rathbun

[THREE years ago] Scientology ‘disconnection’ billboard to be a block from David Miscavige’s office

[FOUR years ago] Scientology documentary ‘Going Clear’ participants getting harassed, threatened

[FIVE years ago] Video Vault: When Scientology basked in the success of giant cucumbers

[SIX years ago] Scientology Mythbusting with Jon Atack: Xenu the Galactic Overlord, Part 1!

[SEVEN years ago] Scientology: Told to Chill in Texas, and Another Embarrassing Admission in Israel

——————–

Bernie Headley has not seen his daughter Stephanie in 5,383 days.

Valerie Haney has not seen her mother Lynne in 1,514 days.

Katrina Reyes has not seen her mother Yelena in 2,016 days

Sylvia Wagner DeWall has not seen her brother Randy in 1,496 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his grandson Leo in 559 days.

Geoff Levin has not seen his son Collin and daughter Savannah in 447 days.

Christie Collbran has not seen her mother Liz King in 3,754 days.

Clarissa Adams has not seen her parents Walter and Irmin Huber in 1,622 days.

Carol Nyburg has not seen her daughter Nancy in 2,396 days.

Jamie Sorrentini Lugli has not seen her father Irving in 3,170 days.

Quailynn McDaniel has not seen her brother Sean in 2,516 days.

Dylan Gill has not seen his father Russell in 11,082 days.

Melissa Paris has not seen her father Jean-Francois in 7,002 days.

Valeska Paris has not seen her brother Raphael in 3,169 days.

Mirriam Francis has not seen her brother Ben in 2,750 days.

Claudio and Renata Lugli have not seen their son Flavio in 3,010 days.

Sara Goldberg has not seen her daughter Ashley in 2,050 days.

Lori Hodgson has not seen her son Jeremy and daughter Jessica in 1,762 days.

Marie Bilheimer has not seen her mother June in 1,288 days.

Joe Reaiche has not seen his daughter Alanna Masterson in 5,377 days

Derek Bloch has not seen his father Darren in 2,517 days.

Cindy Plahuta has not seen her daughter Kara in 2,837 days.

Roger Weller has not seen his daughter Alyssa in 7,693 days.

Claire Headley has not seen her mother Gen in 2,812 days.

Ramana Dienes-Browning has not seen her mother Jancis in 1,168 days.

Mike Rinder has not seen his son Benjamin and daughter Taryn in 5,470 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his daughter Spring in 1,576 days.

Skip Young has not seen his daughters Megan and Alexis in 1,978 days.

Mary Kahn has not seen her son Sammy in 1,850 days.

Lois Reisdorf has not seen her son Craig in 1,433 days.

Phil and Willie Jones have not seen their son Mike and daughter Emily in 1,928 days.

Mary Jane Sterne has not seen her daughter Samantha in 2,182 days.

Kate Bornstein has not seen her daughter Jessica in 13,291 days.

——————–

Posted by Tony Ortega on March 9, 2019 at 07:00

Posted by Tony Ortega on March 9, 2019 at 07:00

E-mail tips to tonyo94 AT gmail DOT com or follow us on Twitter. We also post updates at our Facebook author page. After every new story we send out an alert to our e-mail list and our FB page.

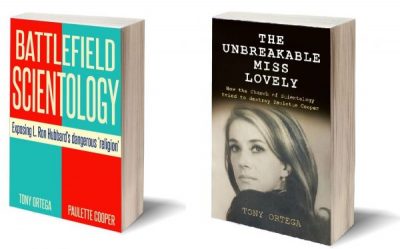

Our new book with Paulette Cooper, Battlefield Scientology: Exposing L. Ron Hubbard’s dangerous ‘religion’ is now on sale at Amazon in paperback and Kindle formats. Our book about Paulette, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology tried to destroy Paulette Cooper, is on sale at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook versions. We’ve posted photographs of Paulette and scenes from her life at a separate location. Reader Sookie put together a complete index. More information can also be found at the book’s dedicated page.

The Best of the Underground Bunker, 1995-2018 Just starting out here? We’ve picked out the most important stories we’ve covered here at the Underground Bunker (2012-2018), The Village Voice (2008-2012), New Times Los Angeles (1999-2002) and the Phoenix New Times (1995-1999)

Other links: BLOGGING DIANETICS: Reading Scientology’s founding text cover to cover | UP THE BRIDGE: Claire Headley and Bruce Hines train us as Scientologists | GETTING OUR ETHICS IN: Jefferson Hawkins explains Scientology’s system of justice | SCIENTOLOGY MYTHBUSTING: Historian Jon Atack discusses key Scientology concepts | Shelly Miscavige, ten years gone | The Lisa McPherson story told in real time | The Cathriona White stories | The Leah Remini ‘Knowledge Reports’ | Hear audio of a Scientology excommunication | Scientology’s little day care of horrors | Whatever happened to Steve Fishman? | Felony charges for Scientology’s drug rehab scam | Why Scientology digs bomb-proof vaults in the desert | PZ Myers reads L. Ron Hubbard’s “A History of Man” | Scientology’s Master Spies | The mystery of the richest Scientologist and his wayward sons | Scientology’s shocking mistreatment of the mentally ill | The Underground Bunker’s Official Theme Song | The Underground Bunker FAQ

Watch our short videos that explain Scientology’s controversies in three minutes or less…

Check your whale level at our dedicated page for status updates, or join us at the Underground Bunker’s Facebook discussion group for more frivolity.

Our non-Scientology stories: Robert Burnham Jr., the man who inscribed the universe | Notorious alt-right inspiration Kevin MacDonald and his theories about Jewish DNA | The selling of the “Phoenix Lights” | Astronomer Harlow Shapley‘s FBI file | Sex, spies, and local TV news | Battling Babe-Hounds: Ross Jeffries v. R. Don Steele