The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) plays an outsized role in Scientology’s roster of villains. On January 4, 1963, five US Federal Marshals, accompanied by an FDA inspector and an officer of the Washington, DC police department, raided the downtown row house of the Washington Scientology org, as well as two other Scientology facilities in Maryland. The raiders seized three truckloads of books and papers and around a hundred E-meters. Newspaper reporters were there to witness it. The following day’s press showed photographs of grim-faced US Marshals carrying out piles of books and E-meters.

For decades, Scientology has cited the raid as a prime example of a government conspiracy against the church. Scientology’s own website links the FDA to a supposed effort by psychiatrists and the US intelligence community to “suppress Dianetics and its assault on the mental health field”. However, declassified FDA records obtained under the Freedom of Information Act by the remarkable R.M. Seibert (whose help was key for me to write this article) show a very different story — one in which Scientology’s problems with the FDA were largely self-created. In fact, far from being part of a conspiracy to target Scientology, the FDA was wary about acting against it. It was pushed into action by political pressure resulting from complaints about Scientology’s false healing claims.

Scientology had been in the sights of the FDA for several years before the raid. The agency’s interest came about because of frequent public complaints about Scientology’s claims of physical healing. These had indisputably originated with founder L. Ron Hubbard himself. Even before he launched Dianetics in June 1950, he had written to the American Psychiatric Association, American Psychological Association and Gerontological Society to claim that his methods could cure illnesses including “migraine headache, ulcers, asthmas, sinusitis and arthritis.” The list of ailments that supposedly could be cured through Dianetics and Scientology grew to include poor eyesight and even cancer.

On his first visit to the UK in December 1952, he told the Daily Express newspaper that “Scientology can cure just about anything.” Hubbard subsequently obtained a fake doctorate from Sequoia University, a notorious Los Angeles ‘degree mill.’ Not coincidentally, it also styled itself the ‘College of Drugless Healing.’ A Scientology delegation later tried to convince Britain’s Ministry of Health to endorse “Dr. Hubbard’s” techniques for use by the National Health Service. The Ministry’s splendidly-named Dr. Tooth was not convinced and the NHS remains a Scientology-free zone to this day.

Such claims prompted hostility from governments and medical authorities on both sides of the Atlantic. They resulted in police forces and regulatory agencies investigating Scientology and its members. In 1953 Hubbard decided to convert Scientology into an ostensibly religious entity. He sought to play down some of the more extravagant claims that had been made for Scientology’s healing powers, but many individual Scientology practitioners continued making them. In one example, Clem W. Johnson, the operator of a Scientology franchise in Orlando, Florida, informed a client in November 1954 that by using Scientology, “any disease or illnesses that you now have, will just vanish through processing.”

Johnson cited several examples of supposed miracle cures: his wife’s hair had turned from “completely gray to only about one third as much now,” a woman’s diseased kidney had been saved, a man with severe arthritis was now “standing straight,” a deaf boy was able to hear after only forty minutes of processing, and a woman who had been completely blind for 37 years was now seeing “flashes of light.” Johnson wrote: “She is sure she will be seeing again within a few more weeks. She plans to return home before Christmas with her sight. We believe she will too.”

Not surprisingly, such claims failed to stand up to scrutiny. Medical groups, politicians and the Better Business Bureau (BBB) received numerous complaints from around the US of bogus claims of healing being made by Scientologists. The BBB pressed the government to act, telling the US Secret Service in March 1958 that Hubbard was “a fraud who is extremely dangerous to the uninformed and the gullible who will contribute money to his schemes or enrol in schools founded by Hubbard.”

The government did act only a month later, although the timing was probably coincidental. Hubbard had been making claims for a couple of years that Scientology was “the only agency, the only people on the face of Earth who can cure the effect of atomic radiation” and promoted a substance which he called Dianazene as an anti-radiation cure. It was in fact simply a mixture of common vitamins and minerals that had no pharmaceutical value whatsoever.

Dianazene was made for Hubbard by Delmar Pharmacal Corp, a Rensselaer, New York company with a shady reputation. The firm was convicted of shipping mislabeled and adulterated drugs in June 1957 and was later sued again by the Food and Drug Administration for fraudulently selling useless ‘weight reduction’ capsules. It is not clear whether Hubbard was aware of the company’s history of pharmaceutical fraud, but using it was clearly a mistake, as it likely meant that the FDA was watching its activities.

On 5 April 1958, FDA inspectors seized and subsequently destroyed 21,000 Dianezene tablets on the grounds that they had been falsely labeled as a preventative and treatment for radiation sickness, and did not contain the advertised ingredients. The seizure was not contested by Scientology. From that point on the FDA kept an increasingly close eye on Scientology’s healing claims.

It was particularly concerned by the E-meter, the electronic device introduced by Hubbard in 1951 as a means of locating the ‘engrams’ he claimed were the cause of mental and physical ailments. The device is simply a dressed-up version of a 19th century invention, the Wheatstone bridge or skin galvanometer, which measures changes in electrical resistance across the user’s skin. No scientific evidence supports Hubbard’s extravagant claims about the device’s utility. (See Mike Rinder’s explanation of how Scientology uses the E-meter.) However, Hubbard had made it a centerpiece of Scientology practice. It was a major revenue stream for him as it could be produced cheaply and sold expensively. At the time, E-meters were made by a single manufacturer in London and exported from there to the US and other countries.

For the FDA, the E-meter was just another in a long list of phony ‘medical’ devices sold by enterprising quacks. It was seen specifically as a variant of a device called a Micro-Dynameter, another form of skin galvanometer that had been prohibited by the FDA under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FDC) Act of 1938. The law gave the FDA the power to ban, seize, destroy or block the import of devices it regarded adulterated or misbranded. A device was regarded as misbranded if, among other issues, its labeling was deemed to be false or misleading.

The FDA enforced the law aggressively against a range of now largely-forgotten devices such as the Drown Radiotherapeutic Instrument, the Zerret Applicator, the Vrilium Tube and the Relax-A-Cisor. During the 12 months to June 30, 1963, a period that included the January 1963 seizure of E-meters, it seized no fewer than 7,986 devices of 54 different types in 358 separate seizure actions.

However, the agency was initially reluctant to move against Scientology because it feared the legal difficulties that would be created by the church’s First Amendment claims. In February 1962, the FDA’s Baltimore District director told the agency’s Division of Regulatory Management: “We once decided that FDC Act jurisdiction, if any, is remote. We see no reason to change our views.” The Division’s Head agreed.

The FDA changed its mind a few months later following complaints from members of the public and Congressional urging. In June 1962, its Dallas office acted to block the import of E-meters from Britain on the grounds that they were “indicated for medical purposes and [are] worthless for such purposes.” Its action was supported by the FDA’s leadership, which noted that the agency had not previously acted “because of the religious type affiliation claimed by the Scientology group.” The FDA’s leadership indicated that it would look at blocking further imports “because there is every indication that the Scientology group practices some type of the healing arts, and the device is apparently a standard part of that practice.”

The following month, the FDA’s Deputy Director of Enforcement interviewed Ross W. Moshier, the father of a young man named Steve Moshier, a brilliant but psychologically troubled Harvard University student. The younger Moshier had dropped out of university and taken up Scientology, using a $5,000 insurance payout to fund his courses. Ross Moshier and a friend of his son were keen to obtain information from the FDA on Scientology to persuade Steve to quit the organization.

Moshier, who was a research chemist at the US Air Force’s Aeronautical Research Laboratory, soon grew frustrated with the FDA’s response and took his case to the FBI, the American Medical Association and others. He noted that he had been told several times that although the government’s agencies regarded Hubbard as a scoundrel, Scientology’s cloak of religion had so far prevented action. He also observed, correctly, that stopping the import and distribution of E-meters would cripple Scientology.

Further complaints came via Francis C. Walter, the US Representative for the 12th District of Pennsylvania. In one case, a man suffering from Parkinson’s Disease was undergoing ‘treatment’ with Scientology despite worsening health. Walter called on the FDA to undertake an investigation. The FDA informed him that it was looking into the matter and that it believed that Scientology was “a pseudo-religious cult which engage[s] in the practice of mental healing for both mental and physical disorders.”

The FDA’s Deputy Commissioner, John L. Harvey, noted that Scientology’s claimed religious status made it extremely difficult for the agency to deal with its practices. He wrote to Walter that he knew of no law that could be used to regulate it, but promised to carry out a fresh investigation to see if the FDC Act was applicable. Enforcement action against Scientology now became a high priority.

On the day after Harvey sent his letter to Walter, the FDA’s Bureau of Enforcement ordered that further imports of E-meters were to be blocked. Six weeks later, on October 17, FDA inspectors visited Scientology orgs in Washington, D.C., New York City and Los Angeles to make enquiries about the E-meter. Hubbard, who was in the UK at the time, was well aware of the FDA’s interest. He told Scientologists that it was a reaction to his earlier actions in “informing the White House we could help them with their fight against Communism” and commented that it seemed “most peculiar that they’d want out of existence a machine that detects Communists while they pretend to be mad about them.”

Hubbard blamed the problems with the FDA on “the irate parents of a [Scientology] student,” evidently a reference to the Moshiers. Although the FDA inspectors were received courteously by the staff of the orgs they inspected, the Scientology leadership evidently took a less cooperative line and attempted to bill the FDA for $329.54 (equivalent to about $2,900 today) of “briefing and consultation rendered” to the inspectors by the Washington org. Not surprisingly, the FDA refused to pay. Another FDA inspector went undercover and enrolled as a student at the Washington Scientology org to gather evidence.

Hubbard responded to the FDA’s investigation by issuing a statement on the nature of the E-meter. He claimed that it was “used to disclose truth to the individual who is being processed and thus free him spiritually … The Electrometer is a valid religious instrument, used in Confessionals, and is in no way diagnostic and does not treat.” He disclaimed any previous claims made for the E-meter and ordered that his statement “must be impressed upon investigating agents as it is only the truth of the matter.”

It was not enough to deter the FDA from carrying out its January 1963 raid. The FDA’s simultaneous ban on E-meter imports was intended to ensure that the confiscated devices could not simply be replaced. This left Scientology with a far more serious problem than the seizure of Dianazene pills five years before. If E-meters could no longer be used or sold, it would render ten years’ worth of E-meter-dependent Scientology procedures useless, and it would deprive Hubbard of an important source of revenue. Ross W. Moshier noted Scientology’s vulnerability regarding the E-meter in a September 1962 letter to the American Medical Association, commenting that “suppression of the E-meter would strike at the vital core, since the ‘religion’ can’t be practiced without the meter.”

Hubbard took the same view, informing Scientologists after the October 1962 inspections that “all processing in the U.S. is in peril.” He was determined to fight the E-meter seizure with every means at Scientology’s disposal and ordered an all-out legal and public relations offensive.

The day after the raid, the Washington Scientology org issued a vehement statement decrying “government bureaucracy gone mad” and “a direct and frightening attack” on freedom of religion, press, and speech. It asked histrionically, “Are we in America today living under a Godless government which intends ultimately to destroy all religions and religious organisations?”

Hubbard issued two statements of his own, claiming that the FDA had “launched an attack upon religion and is seizing and burning books of philosophy.” (The FDA had not in fact burned anything, but was storing the books and meters in a warehouse.) He linked the raid to an earlier letter he had sent to President Kennedy in which he had offered Scientology’s assistance in the space race, and suggested holding “a conference with Mr. Kennedy … to come to some amicable understanding on religious matters.” He made his request conditional on being given “some guarantee of safety of person.” (There is no indication that the government ever responded to him.) Hubbard concluded: “As all of my books have been seized for burning, it looks as though I will have to get busy and write another book.”

Three days later, he told Scientologists that the government’s tactics were comparable to Hitler’s and laid the blame on “Kennedy, a Catholic.” He claimed that the case “could ruin the Kennedy regime, if not the U.S. Government over a longer period.” The US government’s plan, according to Hubbard, was to use Scientology as a test case to “shut down all religious psychology in the U.S.” and “make the U.S. safe for Communists and criminals.”

He explained that “as psychology was founded by Saint Thomas Aquinas of the Roman Catholic Church in the 13th century, and as the FDA was founded when Roosevelt was so friendly with Communism, we think the U.S. Government is trying its strength against all free thought in an effort to set up an NKVD [Soviet secret police] of thought in the Dept. of Health, Education and Welfare.”

In two lectures to Scientologists, he claimed that Kennedy, whom he considered “a jerk,” had personally signed the warrant to raid the Washington org and was part of a plot to create a totalitarian “mental health empire.” He continued to nurse a grudge for years afterwards, telling Scientologists that Kennedy “could have used Scientology” but instead “tried to shoot it down by ordering raids and various berserk actions on Scientology organizations.” He blamed Kennedy’s assassination on the fact that the president had rejected Scientology and thereby “demonstrated how incompetent and how mortal he really was.”

Scientology’s denunciation of the raid was followed by lawsuits on behalf of the church and around 40 Scientologists whose personal E-meters had been among those seized from the Washington org’s premises. Scientology also launched a public relations campaign to embarrass the FDA into reversing course. At Hubbard’s urging, numerous Scientologists wrote to the government and the media to complain about the raid.

The head of the Detroit Scientology org told a local newspaper that the seizure had been a “Communist attack” and that Scientology was “seventh on the Kremlin’s list of organisations that must be destroyed.” The E-meter had been targeted, he said, because it was far more effective than anything the FBI had and could detect a Communist within only fifteen minutes. It had been so effective in South Africa that when word got round that it was going to be used, “a couple of planeloads” of subversives fled the country. (There is no evidence that this claim had any basis in reality.)

Scientology reportedly placed advertisements in newspapers in the Bible Belt to inflame conservative Southern Democrats against the Kennedy Administration. It seems to have had some effect, as the FDA’s files on Scientology include letters from non-Scientologists who wrote to protest the government’s intervention against “an American church.” Numerous Scientologists also petitioned the White House and their Congressional representatives, some of whom contacted the FDA in turn to inquire about the case.

Seemingly taken aback by the case’s escalating profile, the FDA’s Bureau of Enforcement informed district offices throughout the US that their help would be needed to assemble “the entire background of the organisations [of Scientology] and develop evidence concerning the prime movers of the organisations with particular interest in criminal records or actions taken by state and local officials.”

The FDA mounted a major investigation, amassing a huge amount of information on Scientology and interviewing many individuals who had connections to Hubbard. In a remarkable coincidence, it discovered that Hubbard’s first wife Polly, now remarried, was the stepmother of an FDA inspector. She was interviewed shortly before her death from cancer, as were Hubbard’s two estranged elder children, Ron Jr. and Katherine, and various individuals who had left Scientology over the years. The investigation delved into Hubbard’s life in considerable detail, uncovering information that was only to become public knowledge 20 years later.

Hubbard responded by mounting his own investigation using private detectives. In an order to his wife Mary Sue, he instructed that operatives were to find “evidence of collusion between the person who signed the warrant” and the American Psychiatric Association or American Medical Association. Also, he wrote, “we want the name of every doctor who sought to get into this case and we want that doctor’s background. Trace it if possible to Communist connections or orders from APA under AMA. The operative should understand that we have been harassed by anti-American interests in many past cases and that this investigation is a routine assurance that we always take. We have traced 18 out of 22 persons publicly attacking us to criminal or Communist backgrounds.”

The FDA continued periodically to seize imported E-meters for years afterwards. The affair resulted in years of litigation and a vociferous public relations campaign by Scientology. Hubbard sought unsuccessfully to suppress newspaper reporting on the matter, instructing his US attorneys to sue any newspaper that covered the case.

Scientology was not without allies in its campaign against the FDA. Most notably, it enlisted the support of Senator Russell B. Long of Louisiana, who had been contacted by Scientologists complaining about the raid a few days after it took place. The senator invited the Founding Church of Scientology’s attorney and one of its ‘ministers’ to testify at hearings in April 1965 on the topic of invasions of privacy by government agencies. It was the first and probably the only time that an E-meter had been publicly demonstrated on Capitol Hill.

Senator Long subsequently published a book on the issue, though it did not mention Scientology. His criticisms of the FDA were republished by Scientology in a pamphlet titled “The Findings on the U.S. Food and Drug Agency” (sic), which declared — with a remarkable lack of self-awareness — that the FDA was “behaving as a sort of cult, with an almost fanatical urge to save the world.”

In April 1967, the FDA’s long-delayed case against the E-meter finally came to trial. A jury returned a verdict in favor of the FDA after a thirteen-day trial in the US District Court in Washington, DC, ruling that the device was misbranded to make false and misleading therapeutic claims. The presiding judge, John Sirica, ordered that the seized E-meters and Scientology materials were to be destroyed. Sirica subsequently became a target of Scientology’s Guardian’s Office, apparently as a result of his role in the FDA case. A decade later, the FBI seized an “enemies list” from the GO which included a file on the judge, containing personal information that had been obtained covertly.

An appeal by the church was heard by the Court of Appeals in February 1969. It ruled that the seizure had been illegal, accepting the Scientologists’ case that it was a bona fide religion and that the raid had violated its members’ constitutional rights. The government did not contest this claim. In a majority verdict, the court ruled that the E-meters were “a central practice of their religion, akin to a confession in the Catholic church, and hence entirely exempt from regulation or prohibition.”

It was an important victory for Scientology — the first time a US court had accepted its religious bona fides — but it was short-lived, as the government immediately appealed it. Hubbard was delighted with the outcome, awarding a $10,000 bonus to Scientology’s attorney and announcing a million-dollar lawsuit against the FDA. “What psychiatry has in store for it now,” he warned darkly, “is horrible.”

From the start of the 1970s, with the litigation dragging on seemingly interminably, Scientology mounted a ferocious campaign against the FDA. It recruited allies among conservatives, religious groups and critics of the FDA, including the consumer campaigner Ralph Nader. In early April 1971, Hubbard announced that Scientology was carrying out a nationwide PR campaign in newspapers, posters, and on television against “this Fascist book burning agency,” in which it portrayed the FDA’s chief counsel as a Nazi officer.

Scientologists also mounted public demonstrations against the FDA, organised by the Guardian’s Office. Shortly before the appeal was heard in 1971, around 50 Scientologists, some dressed in clerical outfits and wearing large silver crosses, picketed the Federal Building in Seattle and screamed demands to see the FDA’s regional director. The police officer guarding the building was harangued with questions such as, “Are you an animal? Are you an atheist? You’re a barrier and a puppet of the FDA!”

Four Scientologists were allowed in and began demanding of Franklin Clark, the director: “Are you planning to raid the churches in Seattle with drawn guns? Who ordered the harassment of churches by the FDA? Why does the FDA persecute a religion? Why does the FDA want to burn religious books? Why does the FDA consider man to be an animal?” Clark was dismissive, telling them that their charges “have no more backing than the man in the moon.”

Such tactics did not and could not have affected the litigation, but they served other purposes: As theatre, to show other Scientologists that the church was striking back; as propaganda, to publicise Scientology’s cause in the media; and intimidation, to get in the faces of the FDA’s senior officials and convince them that taking on Scientology was more trouble than it was worth. It was an approach that Scientology was to use repeatedly against critics and government officials over several decades, leading ultimately to its acquisition of tax exemption in the US in 1993.

When the appeal was heard in July 1971, Assistant US Attorney Nathan Dodell argued that Scientology had made a “massive number of false and misleading statements” about the E-meter’s usefulness in physical healing. In his ruling, Judge Gerhard A. Gesell ruled that such use was mere “quackery” and that Hubbard had made “extravagant false claims” about its usefulness for healing, which he called a “fraud.” Nonetheless, the judge concluded, Scientology had a viable case for being considered a legitimate religion and was therefore entitled to First Amendment protection.

The FDA’s condemnation of the E-meter for secular purposes was upheld. Scientology was required to add disclaimers that the device was to be “used for, sold or distributed only for use in bona fide religious counselling.” The Scientologists were permitted to continue using the E-meter for non-secular purposes and the confiscated E-meters and materials were returned to the church. “The effect of this judgment,” wrote the judge, “will be to eliminate the E Meter as far as further secular use by Scientologists or others is concerned.”

The ruling enabled both sides to hail it as a victory, though in reality it was more of a draw. The court’s acceptance of the Scientologists’ religious claims set a legal precedent but made no immediate difference to how the government viewed Scientology. Nor did it change how Scientology used the E-meter. Nonetheless, a legacy of the FDA case persists to this day: Every E-meter still has a sticker on it providing a disclaimer that combines the court-ordered text with an additional disclaimer added by Hubbard.

It had an additional legacy: Convinced that the FDA and the Assistant US Attorney Nathan Dodell were part of a vast conspiracy against Scientology, Hubbard ordered that both were to be targeted in a massive campaign of espionage against the US government. Three years after the FDA ruling, two Scientologists were caught by FBI agents as they prepared to burgle Dodell’s office in Washington, DC, precipitating the worst crisis in Scientology’s history.

— Chris Owen

——————–

Scientology’s celebrities, ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and more!

We’ve been building landing pages about David Miscavige’s favorite playthings, including celebrities and ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and we’re hoping you’ll join in and help us gather as much information as we can about them. Head on over and help us with links and photos and comments.

Scientology’s celebrities, from A to Z! Find your favorite Hubbardite celeb at this index page — or suggest someone to add to the list!

Scientology’s ‘Ideal Orgs,’ from one end of the planet to the other! Help us build up pages about each these worldwide locations!

Scientology’s sneaky front groups, spreading the good news about L. Ron Hubbard while pretending to benefit society!

Scientology Lit: Books reviewed or excerpted in our weekly series. How many have you read?

——————–

THE WHOLE TRACK

[ONE year ago] Scientology hip-hop continues to amaze us, and we hope it transports you as well

[TWO years ago] How Humira, the world’s best selling drug, is helping to finance Scientology into the future

[THREE years ago] Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard’s caretaker and friend, Steve ‘Sarge’ Pfauth, 1945-2016

[FOUR years ago] The story of Brian Sheen and his ‘disconnected’ Scientology daughter you haven’t heard

[FIVE years ago] Ken Dandar could use a cool million in his fight against Scientology

[SIX years ago] Mike Rinder: Is the Leah Remini Anonymous Smear Website Coming Soon?

[SEVEN years ago] Scientology Relents: Will Hold a Memorial for Son of Church President, Mother Not Invited

——————–

Bernie Headley has not seen his daughter Stephanie in 5,504 days.

Valerie Haney has not seen her mother Lynne in 1,633 days.

Katrina Reyes has not seen her mother Yelena in 2,137 days

Sylvia Wagner DeWall has not seen her brother Randy in 1,657 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his grandson Leo in 677 days.

Geoff Levin has not seen his son Collin and daughter Savannah in 568 days.

Christie Collbran has not seen her mother Liz King in 3,875 days.

Clarissa Adams has not seen her parents Walter and Irmin Huber in 1,743 days.

Carol Nyburg has not seen her daughter Nancy in 2,517 days.

Jamie Sorrentini Lugli has not seen her father Irving in 3,291 days.

Quailynn McDaniel has not seen her brother Sean in 2,637 days.

Dylan Gill has not seen his father Russell in 11,203 days.

Melissa Paris has not seen her father Jean-Francois in 7,122 days.

Valeska Paris has not seen her brother Raphael in 3,290 days.

Mirriam Francis has not seen her brother Ben in 2,871 days.

Claudio and Renata Lugli have not seen their son Flavio in 3,132 days.

Sara Goldberg has not seen her daughter Ashley in 2,171 days.

Lori Hodgson has not seen her son Jeremy and daughter Jessica in 1,883 days.

Marie Bilheimer has not seen her mother June in 1,409 days.

Joe Reaiche has not seen his daughter Alanna Masterson in 5,498 days

Derek Bloch has not seen his father Darren in 2,638 days.

Cindy Plahuta has not seen her daughter Kara in 2,958 days.

Roger Weller has not seen his daughter Alyssa in 7,814 days.

Claire Headley has not seen her mother Gen in 2,933 days.

Ramana Dienes-Browning has not seen her mother Jancis in 1,288 days.

Mike Rinder has not seen his son Benjamin and daughter Taryn in 5,591 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his daughter Spring in 1,697 days.

Skip Young has not seen his daughters Megan and Alexis in 2,099 days.

Mary Kahn has not seen her son Sammy in 1,971 days.

Lois Reisdorf has not seen her son Craig in 1,554 days.

Phil and Willie Jones have not seen their son Mike and daughter Emily in 2,049 days.

Mary Jane Sterne has not seen her daughter Samantha in 2,303 days.

Kate Bornstein has not seen her daughter Jessica in 13,412 days.

——————–

Posted by Tony Ortega on July 11, 2019 at 07:00

Posted by Tony Ortega on July 11, 2019 at 07:00

E-mail tips to tonyo94 AT gmail DOT com or follow us on Twitter. We also post updates at our Facebook author page. After every new story we send out an alert to our e-mail list and our FB page.

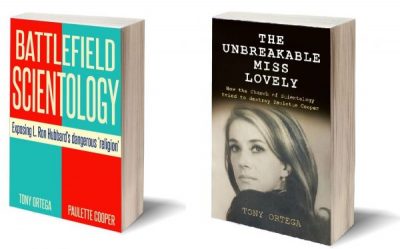

Our new book with Paulette Cooper, Battlefield Scientology: Exposing L. Ron Hubbard’s dangerous ‘religion’ is now on sale at Amazon in paperback and Kindle formats. Our book about Paulette, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology tried to destroy Paulette Cooper, is on sale at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook versions. We’ve posted photographs of Paulette and scenes from her life at a separate location. Reader Sookie put together a complete index. More information can also be found at the book’s dedicated page.

The Best of the Underground Bunker, 1995-2018 Just starting out here? We’ve picked out the most important stories we’ve covered here at the Underground Bunker (2012-2018), The Village Voice (2008-2012), New Times Los Angeles (1999-2002) and the Phoenix New Times (1995-1999)

Other links: BLOGGING DIANETICS: Reading Scientology’s founding text cover to cover | UP THE BRIDGE: Claire Headley and Bruce Hines train us as Scientologists | GETTING OUR ETHICS IN: Jefferson Hawkins explains Scientology’s system of justice | SCIENTOLOGY MYTHBUSTING: Historian Jon Atack discusses key Scientology concepts | Shelly Miscavige, ten years gone | The Lisa McPherson story told in real time | The Cathriona White stories | The Leah Remini ‘Knowledge Reports’ | Hear audio of a Scientology excommunication | Scientology’s little day care of horrors | Whatever happened to Steve Fishman? | Felony charges for Scientology’s drug rehab scam | Why Scientology digs bomb-proof vaults in the desert | PZ Myers reads L. Ron Hubbard’s “A History of Man” | Scientology’s Master Spies | The mystery of the richest Scientologist and his wayward sons | Scientology’s shocking mistreatment of the mentally ill | The Underground Bunker’s Official Theme Song | The Underground Bunker FAQ

Watch our short videos that explain Scientology’s controversies in three minutes or less…

Check your whale level at our dedicated page for status updates, or join us at the Underground Bunker’s Facebook discussion group for more frivolity.

Our non-Scientology stories: Robert Burnham Jr., the man who inscribed the universe | Notorious alt-right inspiration Kevin MacDonald and his theories about Jewish DNA | The selling of the “Phoenix Lights” | Astronomer Harlow Shapley‘s FBI file | Sex, spies, and local TV news | Battling Babe-Hounds: Ross Jeffries v. R. Don Steele