I’m a guy

A guy who seems calm but plays when he plays

A guy who goes completely crazy when the right time comes

A guy who has bulging ideas rather than muscles

South Korean K-pop star Psy’s 2012 megahit Gangnam Style satirises posers and wannabes who put on airs and claim to be something that they are not. “People who are actually from Gangnam never proclaim that they are,” he observes.

He might almost have been thinking of Scientology’s founder L. Ron Hubbard, who was claimed by Scientology publications to have been the “Provost Marshal of Korea” in 1945. The apologist journal CESNUR has recently questioned whether the claim came from Hubbard himself. I’ve reviewed the “Provost Marshal” claim in my recent book Ron the War Hero, but I have since come across further information linking it definitively to Hubbard, despite CESNUR’s protestations to the contrary.

This claim is said to have first been made in a biography written for a Who’s Who-type publication in the early 1950s, but its earliest appearance that I have been able to confirm is in a letter attributed to L. Ron Hubbard dated June 29, 1960. After a local Australian newspaper reported that the New South Wales police were investigating Scientology, Hubbard sent an indignant letter to the state police. “My personal feeling is that you have a subversive infiltration in your area,” he wrote. “As one trained as the Provost Marshal of Korea, I have a good grip on Asian subversion and do not intend it to ruin Scientology in any area.”

The claim surfaced again in A Report to Members of Parliament on Scientology, a 1968 publication issued to members of the British Parliament following that country’s introduction of a ban on the immigration of foreign Scientologists.

So is there any truth in the claim, and if not, where does it come from? A review of the evidence shows definitively that it isn’t true that Hubbard was “Provost Marshal of Korea” – and a discovery that I made recently in the South African national archives shows that the claim came directly from Hubbard himself.

First, what is a Provost Marshal and what does he do? In the United States armed forces, the most senior military police official at the theatre, corps, division, and brigade level and for each garrison is known as a provost marshal, with the seniormost designated the Provost Marshal General. In peacetime the role usually deals with criminal offences committed by military personnel. However, policing in post-war Korea presented a much bigger challenge.

The country had been occupied by Japan for forty years and policed brutally by a predominantly Japanese police force. Only thirty percent of Korea’s police personnel at the time of the Japanese surrender in August 1945 were Koreans, almost all in minor positions. The force was hated and feared by the Korean population, who wasted no time in throwing off its authority as soon as the Japanese were defeated.

The US military government that replaced the Japanese occupation authorities decided that it had to remove the Japanese-dominated police immediately. The US set about creating an entirely Korean police force to replace the existing force. This task was taken on by Brigadier General Lawrence E. Schick, the Provost Marshal General of XXIV Corps of the US Tenth Army. XXIV Corps had landed at Incheon on September 8, 1945 and established the US Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) shortly afterwards. This lasted until the South Korean state was established in August 1948.

Hubbard clearly could not have been “Provost Marshal of Korea” – there was no such position. The man who actually did perform that role in practice was many ranks more senior than Hubbard, who was at the time a Navy lieutenant with an indifferent service record. It was also an Army responsibility, so a naval officer would not have been eligible for the position in the first place.

Furthermore, Hubbard had no background in policing whatsoever. He had been kicked out of Australia after disrupting a secret US Army operation, lost his first command for arguing with his superior, lost his second command for disobeying orders and spent the rest of the war in training, in hospital or in heavily supervised roles. There was nothing in his record that would have made anyone consider him a candidate for such an important role.

Hubbard did, however, attend the US School of Military Government at Princeton University between September 1944 and January 1945. He had joined following a general request from the US Navy for applicants “for intensive training with eventual assignment to foreign duty as civil affairs officers in occupied areas.” In his letter of application, dated September 9, 1944, he wrote that he had been “educated as a civil engineer,” though he did not mention that he had only completed two out of three years of his course and had failed to graduate.

He also claimed to be conversant in “Japanese, Spanish, Chamorro, Tagalog, Pekin [sic] Pidgin, Shanghai Pidgin,” which would have been no mean feat considering that he had been in Japan and China for only a few days, as a teenager, in the late 1920s. In addition, he claimed that he was “familiar with the sociology and governments of North China, Japan, the Philippines” – again exaggerating his brief tourist visits in the 1920s – and claimed that he was “experienced in handling natives, all classes, in various parts of [the] world, as laboring crews, students or business associates.” His actual experience was limited to helping to teach English to Chamorro children on Guam when he was a teenager and briefly supervising Puerto Rican labourers in a failed mining venture in 1932.

However, the Navy probably did not probe too deeply into his claims, as the US armed forces were critically short of personnel for the post-war military administrations they were planning to establish. Years later, Hubbard acknowledged that he had got onto the course because the government was desperate for anyone who could do the job. “Anybody who had experience with Asia was welcome as the flowers of spring up at Princeton where they were being trained,” he said in a 1951 Dianetics lecture, “so they pulled me out of the Pacific and I went to Princeton in the last few months of the war.”

The training consisted of a series of crash courses in the geography, history, culture, economy and government of the areas that were to be occupied. The students studied topics including international law, psychology, civil administration, political science and languages. As a contemporary journal put it, the goal was to enable the trainee administrators:

[T]o handle such contacts with the civilian populations of the western and southwestern Pacific as might be expected to develop in connection with naval operations in that area. They were to be trained as officers capable of handling liaison activities with the Army, with such civilian agencies as may impinge upon the Navy, with our allies, and with the native populations of the area, and also as civil affairs officers equipped to participate in the administration of such military governments as might in the course of events be established under naval control.

Hubbard was among those undergoing training for duty as a military administrator, though a later Scientology account implies that he was actually a tutor, claiming that he gave lessons on “Oriental Justice and law enforcement.” There is no evidence of this from his service record.

Hubbard’s friend and editor John W. Campbell wrote warmly of Hubbard’s move to Princeton, which he seemed to think would be a front-line role: “He’ll go in with the first wave of landing craft, unarmed, but in navy officer’s uniform, to take charge of civilians trapped in the newly formed beachhead.” In reality, he would have worked well behind the front lines to implement the military occupation of reconquered territories. Many of the trainee administrators were in fact conscientious objectors.

Hubbard seems to have used his time at Princeton principally as an opportunity to get away from the stultifying boredom of his posting aboard the cargo ship USS Algol, to hang out with his science fiction writer friends in New York City, and to pursue an affair with a woman named Ferne. Although he did reasonably well in his course – he finished about midway in a class of three hundred and was recommended for a promotion – he probably had no intention of going abroad.

On April 2, 1945, he and his colleagues were assigned to duty with a civil affairs team outside the continental limits of the United States, which would most probably have been in the Pacific or south-east Asia. But just one week later Hubbard turned up at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in California complaining of stomach pains. He was promptly hospitalised for medical examinations and remained on the sick list until he was mustered out of active duty in February 1946. He certainly did not leave the US during this time, as his letters and naval records show that he was on the US West Coast throughout 1945.

As this chronology and Hubbard’s own naval record shows, he never went anywhere near Korea. It’s quite possible, though, that his assignment in April 1945 was to the formative Office of the Provost Marshal General for Korea. It was not necessarily a very attractive assignment, as the US armed forces expected to have to fight their way into Japan and Korea, before the dropping of the two atomic bombs in August 1945 abruptly ended the war. He showed no interest in actually taking up a role in military government and instead unsuccessfully requested a return to sea duty.

Hubbard clearly never served in any capacity in Korea. So where did the claim that he did come from?

The three published sources for the claim cannot be attributed definitively to Hubbard, though it is overwhelmingly likely that at the very least he authorised them. The 1950s Who’s Who entry was issued on his behalf, and the 1968 Report to Members of Parliament was published by the Church of Scientology. It is inconceivable that either would have been issued without being reviewed by him first.

The 1960 letter bears Hubbard’s name, but as CESNUR points out, it was sent from the Melbourne Scientology organisation, not Hubbard’s home at Saint Hill Manor in England, where he was certainly present at the time it was written. It bears a notation “by CW” indicating that someone else had a hand in issuing it. CESNUR claims that this indicates that someone else wrote the letter on Hubbard’s behalf and it could not have been telexed due to its length and layout. CESNUR’s assertion that it was not written in Hubbard’s usual style is dubious. The letter is very much of a piece with Hubbard’s formal communications with government agencies, of which examples also exist in the UK, US and South African national archives.

Scientology also certainly used telexes for lengthy communications. Since the early days of Dianetics, Hubbard had made extensive use of telexes for keeping in touch with his worldwide empire. Neither he nor his followers shied away from using lengthy telexes to issue statements. After Sir John Foster issued his eponymous report on Scientology in the UK in 1973, Scientology’s chief spokesman David Gaiman telexed a statement to the South African press – republished in the local edition of Scientology’s publication Freedom – that was much longer than Hubbard’s 1960 letter. Neither length nor formatting seem to have been issues. Gaiman’s original telex would have had to be retyped for publication. This is the most likely explanation of the “by CW” notification on Hubbard’s letter – that it represents the initials of the typist in Melbourne who reformatted it onto letterheaded paper.

Nonetheless, CESNUR is right to point out that the chain of attribution to Hubbard is not unbroken: that is, someone else had to be involved, who would theoretically have had an opportunity to add the claim without Hubbard’s knowledge. Fortunately, there are at least two unpublished examples of the claim coming directly from Hubbard personally. They demonstrate that he made this claim himself, and that it was not just the result of over-enthusiastic Scientologists misinterpreting or exaggerating his achievements.

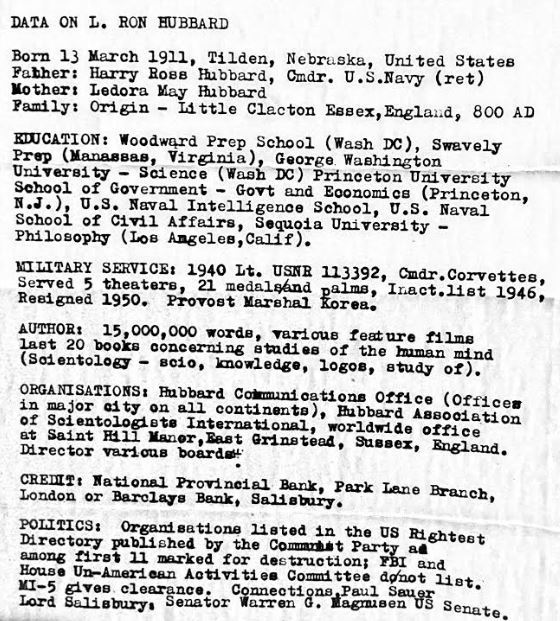

The first was a document titled “Data Sheet on Lafayette Ronald Hubbard” in Hubbard’s own handwriting, which was written for use by his public relations staff and for publication. Gerry Armstrong, Hubbard’s former biographical researcher, highlighted this document and its false claim about the “Provost Marshal” position in a letter that he wrote in November 1981 when he was still in Scientology. While the original handwritten document appears never to have been published, its full text is in the public domain. Its authenticity has never been disputed.

The second is a document which has never been published before but which I found recently in the South African government’s archives in Pretoria. Probably around the start of June 1966 (the exact date is unclear but an official reply dated June 10 is preserved), Hubbard sent two confidential memos to the South African Prime Minister from his home in Salisbury, Rhodesia (now Harare, Zimbabwe). He complained that local South African diplomats were balking at his request to be granted a visa so that he could come to South Africa and deal with attacks on Scientology in the local press.

Along with the memos, he attached a short typewritten document giving “Data on L. Ron Hubbard.” It was apparently intended to convey why he was so important that his affairs merited the Prime Minister’s intervention. Its content is significantly different from the other data sheets and was clearly written at the same time as his memos, as it echoes their contents and alludes to his short time in Salisbury. As well as listing the false “Provost Marshal Korea” claim, it also gives information which is provided in none of the other data sheets: Hubbard’s military service number, his supposed family origins in England, his London and Salisbury banks and his political connections in the UK, US and South Africa.

The document is particularly significant as its provenance can be attributed directly to Hubbard personally. It was sent from his private address in Salisbury, not a Scientology org; there is no indication that anyone else was involved in it, or even knew about it; it lists information which was likely known only to him and perhaps his wife, who was still in England; and it accompanied a private and confidential letter which he clearly wrote himself. It is highly likely that it was personally typed by Hubbard to accompany his memos to the South African Prime Minister. So it seems safe to conclude that the “Provost Marshal” claim came directly from Hubbard.

In the overall scheme of things, Hubbard’s lie about his supposed Korean service is fairly unimportant. It wasn’t a case of “stolen valour” and nobody got hurt along the way. It does, however, demonstrate once again his propensity to lie and exaggerate about his achievements. As Gerry Armstrong rightly said in his 1981 letter, “If we present inaccuracies, hyperbole or downright lies as fact or truth, it doesn’t matter what slant we give them, if disproved the man will look, to outsiders at least, like a charlatan.”

— Chris Owen

——————–

Scientology’s celebrities, ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and more!

We’ve been building landing pages about David Miscavige’s favorite playthings, including celebrities and ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and we’re hoping you’ll join in and help us gather as much information as we can about them. Head on over and help us with links and photos and comments.

Scientology’s celebrities, from A to Z! Find your favorite Hubbardite celeb at this index page — or suggest someone to add to the list!

Scientology’s ‘Ideal Orgs,’ from one end of the planet to the other! Help us build up pages about each these worldwide locations!

Scientology’s sneaky front groups, spreading the good news about L. Ron Hubbard while pretending to benefit society!

Scientology Lit: Books reviewed or excerpted in our weekly series. How many have you read?

——————–

THE WHOLE TRACK

[ONE year ago] Opportunity missed: What Erika Christensen should have been asked about Scientology

[TWO years ago] Source: Scientology ship avoiding Dutch waters after evading surprise government search

[THREE years ago] Nearly four years after Stacy Murphy’s death, Scientology files motion to kill much of lawsuit

[FOUR years ago] ‘Book ’em, Danno’: Just for fun, L. Ron Hubbard’s fingerprints, revealed!

[FIVE years ago] Ryan Hamilton files lawsuit 14 against Scientology’s drug rehab, and other updates

[SIX years ago] In His New Book, Is Neil Gaiman Exorcising His Scientology Past?

[EIGHT years ago] Scientology “Goons” Rough Up Aussie TV Journos (Video)

[TEN years ago] Scientology’s Leader a Sadistic Slapper, Say Top-Level Defectors: St. Pete Times

——————–

Bernie Headley has not seen his daughter Stephanie in 5,484 days.

Valerie Haney has not seen her mother Lynne in 1,613 days.

Katrina Reyes has not seen her mother Yelena in 2,117 days

Sylvia Wagner DeWall has not seen her brother Randy in 1,637 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his grandson Leo in 657 days.

Geoff Levin has not seen his son Collin and daughter Savannah in 548 days.

Christie Collbran has not seen her mother Liz King in 3,855 days.

Clarissa Adams has not seen her parents Walter and Irmin Huber in 1,723 days.

Carol Nyburg has not seen her daughter Nancy in 2,497 days.

Jamie Sorrentini Lugli has not seen her father Irving in 3,271 days.

Quailynn McDaniel has not seen her brother Sean in 2,617 days.

Dylan Gill has not seen his father Russell in 11,183 days.

Melissa Paris has not seen her father Jean-Francois in 7,102 days.

Valeska Paris has not seen her brother Raphael in 3,270 days.

Mirriam Francis has not seen her brother Ben in 2,851 days.

Claudio and Renata Lugli have not seen their son Flavio in 3,112 days.

Sara Goldberg has not seen her daughter Ashley in 2,151 days.

Lori Hodgson has not seen her son Jeremy and daughter Jessica in 1,863 days.

Marie Bilheimer has not seen her mother June in 1,389 days.

Joe Reaiche has not seen his daughter Alanna Masterson in 5,478 days

Derek Bloch has not seen his father Darren in 2,618 days.

Cindy Plahuta has not seen her daughter Kara in 2,938 days.

Roger Weller has not seen his daughter Alyssa in 7,794 days.

Claire Headley has not seen her mother Gen in 2,913 days.

Ramana Dienes-Browning has not seen her mother Jancis in 1,268 days.

Mike Rinder has not seen his son Benjamin and daughter Taryn in 5,571 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his daughter Spring in 1,677 days.

Skip Young has not seen his daughters Megan and Alexis in 2,079 days.

Mary Kahn has not seen her son Sammy in 1,951 days.

Lois Reisdorf has not seen her son Craig in 1,534 days.

Phil and Willie Jones have not seen their son Mike and daughter Emily in 2,029 days.

Mary Jane Sterne has not seen her daughter Samantha in 2,283 days.

Kate Bornstein has not seen her daughter Jessica in 13,392 days.

——————–

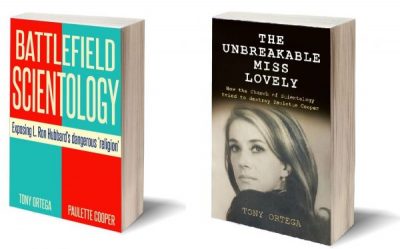

Posted by Tony Ortega on June 21, 2019 at 07:00

Posted by Tony Ortega on June 21, 2019 at 07:00

E-mail tips to tonyo94 AT gmail DOT com or follow us on Twitter. We also post updates at our Facebook author page. After every new story we send out an alert to our e-mail list and our FB page.

Our new book with Paulette Cooper, Battlefield Scientology: Exposing L. Ron Hubbard’s dangerous ‘religion’ is now on sale at Amazon in paperback and Kindle formats. Our book about Paulette, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology tried to destroy Paulette Cooper, is on sale at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook versions. We’ve posted photographs of Paulette and scenes from her life at a separate location. Reader Sookie put together a complete index. More information can also be found at the book’s dedicated page.

The Best of the Underground Bunker, 1995-2018 Just starting out here? We’ve picked out the most important stories we’ve covered here at the Underground Bunker (2012-2018), The Village Voice (2008-2012), New Times Los Angeles (1999-2002) and the Phoenix New Times (1995-1999)

Other links: BLOGGING DIANETICS: Reading Scientology’s founding text cover to cover | UP THE BRIDGE: Claire Headley and Bruce Hines train us as Scientologists | GETTING OUR ETHICS IN: Jefferson Hawkins explains Scientology’s system of justice | SCIENTOLOGY MYTHBUSTING: Historian Jon Atack discusses key Scientology concepts | Shelly Miscavige, ten years gone | The Lisa McPherson story told in real time | The Cathriona White stories | The Leah Remini ‘Knowledge Reports’ | Hear audio of a Scientology excommunication | Scientology’s little day care of horrors | Whatever happened to Steve Fishman? | Felony charges for Scientology’s drug rehab scam | Why Scientology digs bomb-proof vaults in the desert | PZ Myers reads L. Ron Hubbard’s “A History of Man” | Scientology’s Master Spies | The mystery of the richest Scientologist and his wayward sons | Scientology’s shocking mistreatment of the mentally ill | The Underground Bunker’s Official Theme Song | The Underground Bunker FAQ

Watch our short videos that explain Scientology’s controversies in three minutes or less…

Check your whale level at our dedicated page for status updates, or join us at the Underground Bunker’s Facebook discussion group for more frivolity.

Our non-Scientology stories: Robert Burnham Jr., the man who inscribed the universe | Notorious alt-right inspiration Kevin MacDonald and his theories about Jewish DNA | The selling of the “Phoenix Lights” | Astronomer Harlow Shapley‘s FBI file | Sex, spies, and local TV news | Battling Babe-Hounds: Ross Jeffries v. R. Don Steele