Chris Owen’s book ‘Ron the War Hero’ is now for sale, and he’s giving us a look today at one of the best things in it — absolutely stunning material, previously unpublished, about the most ignominious of L. Ron Hubbard’s blunders during a disastrous World War II experience. Read this and keep in mind that Hubbard spent decades promoting himself as a major hero in Australia.

Twenty years ago this year, I wrote a set of web pages called “Ron the War Hero,” a look at L. Ron Hubbard’s decidedly inglorious career with the United States Navy during World War II. Over the last two years I’ve rewritten and greatly expanded it with the aid of new material that’s become available since 1999. The all-new Ron the War Hero is now available in book form from Silvertail Books.

Among the stories that it reveals is perhaps the darkest and longest-concealed secret of Hubbard’s life: How his incompetence contributed to the loss of 16 lives, two ships, thousands of tons of desperately-needed supplies, and some highly sensitive Allied military secrets. Here, for the first time, is the story of how Hubbard helped to sink two ships — not the enemy’s, but his own side’s.

The Church of Scientology’s largely fictional account of Hubbard’s wartime service portrays him participating in secret operations in Australia, battling Nazi U-boats in the North Atlantic, taming a crew of naval convicts, and sinking Japanese submarines off the coast of Oregon. His service supposedly led to what is now the foundational myth of Scientology: That he was “crippled and blinded” in action and cured himself through his revolutionary mental therapies.

While much of this was untrue, it turns out that Hubbard really was involved in secret operations in Australia. Unfortunately for all concerned, he blundered catastrophically. His conduct led to him being ordered to leave Australia after spending just over four weeks in the country. Hubbard’s abrupt dismissal has been unexplained in previous accounts, but the reason behind it turns out to be as much tragic as farcical.

Hubbard arrived in Australia on January 11, 1942 as one of the first US military personnel sent to the Western Pacific after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the previous month. He was never intended to stay there: He had been posted to the US naval base at Cavite in the Philippines, where he was assigned to work in censorship. However, the Japanese advance across Southeast Asia was so rapid that he never got to Cavite.

Left at a loose end in Brisbane, he was drafted to work for the US Army’s Base Section Three under Colonel Alexander L. P. Johnson. The US armed forces in Australia were in the very earliest stages of establishing themselves in a series of bases around the country. They faced a severe shortage of trained personnel.

As Hubbard was one of only a few US naval officers in the city, Col Johnson assigned him the job of handling naval shipping movements in Brisbane harbor, despite his complete lack of any prior experience or training in doing the job.

Hubbard likely worked from Base Section Three’s offices at Somerville House, a requisitioned girls’ school in a suburb of Brisbane. In late January 1942 he became closely involved in a secret US Army operation to resupply General Douglas MacArthur’s besieged forces on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. Eleven thousand American and Filipino troops were cut off on the heavily fortified island of Corregidor, under constant attack from the Japanese. Up to 120,000 more soldiers were squeezed into a pocket at Bataan. Ammunition and rations were in short supply, and conditions were increasingly desperate.

Hubbard’s involvement in the operation is documented in a report (which you can read here) that he wrote on February 3, 1942 after his actions came under scrutiny from his superiors. The report is not part of his Navy files, and the original may have been destroyed in a July 1973 fire that wiped out a large number of US Army records. Its details can be corroborated with other sources and its devastating implications make it highly unlikely to be a forgery.

The report seems to have been disclosed by the Church of Scientology in the course of its litigation against the Boston attorney Michael Flynn in the early 1980s. It was probably obtained through Scientology’s campaign of Freedom of Information Act litigation – the legal side of the notorious Snow White Project.

Ironically, its disclosure was as part of a “dead agent pack” that was intended to prove that Hubbard really was a war hero. But it tells a very different tale about how Hubbard’s incompetence and indiscipline led to his personal downfall and the disaster that befell two Allied ships.

After MacArthur was cut off and besieged, the US Army planned to break the Japanese blockade and resupply the Allied defenders on Luzon. A number of civilian ships were chartered in Brisbane for the operation.

The first vessel to be selected, the MV Don Isidro, was a three-year-old German-built steamship with a 68-man Filipino crew. She had operated before the war as a luxury 3,200-ton passenger transport between the Philippine Islands. Under her experienced captain, Rafael J. Cisneros, she had made a daring escape through the blockade to reach Australia. The crew agreed to make an even more dangerous return journey to the Philippines, with the promise of bonus wages.

The Army loaded the vessel with 700 tons of rations and over 1.7 million rounds of ammunition, as well as installing five .50-caliber heavy machine guns to protect against air attack. Led by 2nd Lieutenant Joseph F. Kane, 15 volunteers from the 453d Ordnance (Aviation) Bombardment Company volunteered to serve aboard Don Isidro on her dangerous journey to the Philippines.

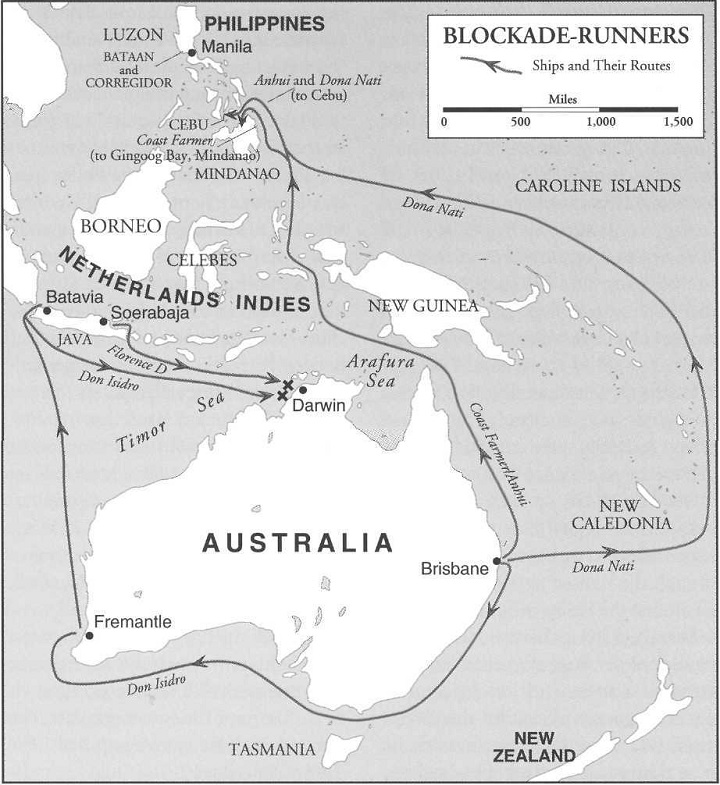

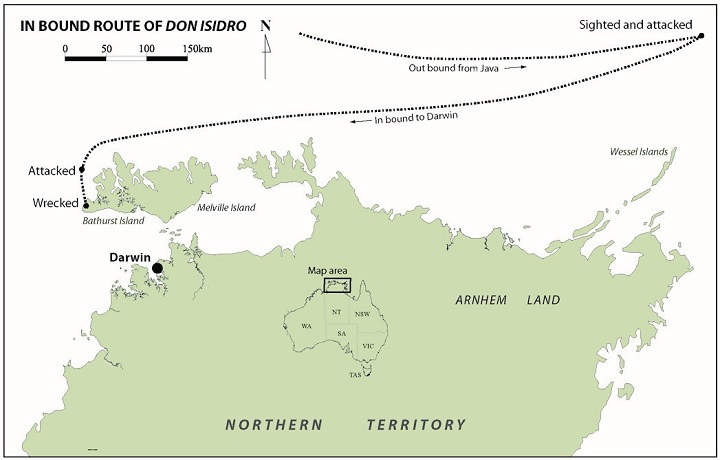

Likely on Col Johnson’s orders, Hubbard was given the task of planning routes for several of the blockade-running ships to sail from Brisbane to the Philippines. Don Isidro and two other ships named by Hubbard, the Coast Farmer and Admiral Halstead, were meant to travel to Gingoog Bay in Mindanao in the southern Philippines.

The supplies carried aboard were to be transported from there to MacArthur’s forces. The shortest route to Mindanao from Brisbane would have been north along the east coast of Australia, west through the Torres Strait between Australia and New Guinea, and then north through a gap in the island chain of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia).

However, Hubbard considered that far too dangerous. He was concerned that Japan’s invasions of the Dutch East Indies and New Guinea had brought Japanese air power within reach of northern Australia. Instead of sending Don Isidro north, he sent her in the opposite direction — “three thousand miles out of her way”, in the subsequent biting words of Commander Lewis R. Causey, the US Naval Attaché to Australia.

Don Isidro was diverted on a meandering route around the south coast of Australia to the Indian Ocean port of Fremantle, before sailing on to as-yet unoccupied Batavia (now Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies. From there, she was routed south and east along the south coast of Java. She was then to head north from the Timor Sea towards the Philippines.

The diversion was ordered by Colonel Johnson, but it was clearly Hubbard’s idea. He justified it on the basis of seeing an intelligence map showing the disposition of enemy forces in the region. (Again, this was a task he had no training to perform; he was trained in censorship, not analysing military intelligence.)

Hubbard sought and obtained an interview with Major-General Julian Barnes, the most senior US officer in Australia, “on the grounds that the general must be informed of the folly of sending the Coast Farmer and Admiral Halstead to Luzon and the further folly of routing them past Thursday Island, New Guinea and past the Japanese land sea and air bases on Ambione [Ambon]”.

His initiative — bypassing the US Navy’s entire chain of command in Australia — was clearly not welcomed by his naval superiors. Hubbard’s credibility was further damaged by a fiasco in handling highly sensitive operational information. His top secret routing order for the Don Isidro went missing when it was sent to US forces headquarters in Melbourne. Its sensitivity was such that it was supposed to have been hand-delivered by a courier travelling by plane.

Hubbard presumably sent it by some other less reliable method, which resulted in it going missing. This was potentially catastrophic: It could have resulted in the entire resupply operation being compromised. He was ordered to immediately and personally courier a fresh copy of the routing order to Melbourne on January 30, 1942.

Rather undiplomatically, Hubbard appears to have attempted to cast the blame for the loss of the order on Sir Thomas Gordon, a senior British official in charge of wartime shipping in Australia. It’s not clear what he imagined Gordon’s role to be. It most likely related to the means by which he chose to have the order sent to Melbourne, presumably via a route which was under Gordon’s authority.

It seems likely that Hubbard made insinuations about Gordon’s loyalty to the Allied cause. He was ordered to remain overnight in Melbourne and make himself available the following day for an interview with Commander Causey and Colonel Van Santvoord Merle-Smith, the US Military Attaché.

Hubbard had a long history of denigrating the loyalty of those around him. In 1940, he wrote to the FBI to denounce the steward of the New York hotel where he was staying as a Nazi spy, and on his last day in Australia he took the time to denounce several people in Brisbane as supposed Japanese and German agents. After founding Dianetics in 1950, he denounced numerous colleagues and ex-employees — and even his own wife — as supposed Russian agents. There’s no sign that any of his denunciations were taken seriously, and an FBI agent wrote, “appears mental,” on one of his letters of denunciation.

The mood of Hubbard’s superiors cannot have been improved by his complaint that he could not spare the time to see them, as he claimed he was needed urgently in Brisbane. This evidently did not achieve anything other than antagonizing them. He soon found that they had already decided how they were going to deal with him even before he arrived at the meeting.

The interview was a comprehensive humiliation for Hubbard. He was grilled by Merle-Smith, who quizzed “the extent of his knowledge of Sir Thomas Gordon.” By this time, Hubbard must have realized how badly he had blundered, but his pride evidently prevented him admitting that he was wrong.

“This officer divulged very little,” Hubbard wrote in his subsequent report. “This officer refused to let Colonel Smith [sic] have entered into the record words which Colonel Smith said as coming from this officer, ‘Then you say that you have no knowledge whatsoever that Sir Thomas Gordon is anything but a loyal citizen’ (paraphrase). This officer said he admitted no extent of any knowledge whatsoever and would not admit to knowing nothing about Sir Thomas Gordon. This was entered on the record as ‘Hubbard uncertain’.”

According to Hubbard, Causey told him at the end of the meeting: “I have sent a message to the CinC Asiatic as of this morning stating that I wish you to be removed from Brisbane, stating that you are making a nuisance of yourself. You have never been under my orders and I consider you as having nothing to do with me. If you wish to serve with Johnson, that is up to you.”

Hubbard evidently took this hard. He admitted in his report that he had walked out of the meeting at that point, in a gross breach of military decorum: “Without taking leave or further addressing either officer, who were now standing in the hall, their conversation and comment overheard widely, this officer put on his cap and left the building.” He followed up by writing his five-page account of the situation, addressed to Colonel Johnson in Brisbane, in which he was critical of the two attachés and implied they were plotting against Johnson.

This further act of indiscipline was evidently the last straw for Causey. He now wanted Hubbard out of Australia, not just Brisbane, and ordered him back to the United States on February 11.

“By assuming unauthorized authority and attempting to perform duties for which he has no qualifications, he became the source of much trouble,” Causey wrote in a cable. “This officer is not satisfactory for independent duty assignment. He is garrulous and tries to give impressions of his importance. He also seems to think that he has unusual ability in most lines.”

Hubbard spent about three weeks more in Australia, waiting for a ship to take him home. To keep him from committing any further harm, Causey removed him from Base Section Three and brought him into the naval chain of command. Hubbard was placed in a bare office on the other side of Brisbane and assigned to keep a chair warm for the incoming US Naval Observer and his staff. On March 9, he was on his way aboard the SS Pennant.

Hubbard’s removal from Australia was not simply the result of personality clashes with his superiors or inter-service rivalries. He had been responsible for two very serious operational failings: The loss of the routing order, which put at risk the whole operation, and his decision to divert the Don Isidro, costing it days that could not be spared. In addition, his egotistical and disrespectful approach to his superiors showed that he could not be relied upon in any unsupervised position of responsibility.

While Hubbard was preparing to leave Australia, the Don Isidro was still on her extended voyage to the Philippines. Unknown to her captain, however, the delay in her journey had put her directly in the way of Japan’s largest-ever military operation against Australia. On February 18, 1942, the Don Isidro was ambushed by a lone Japanese bomber about 80 miles off the Australian coast. Thanks to quick evasive action, she escaped unscathed.

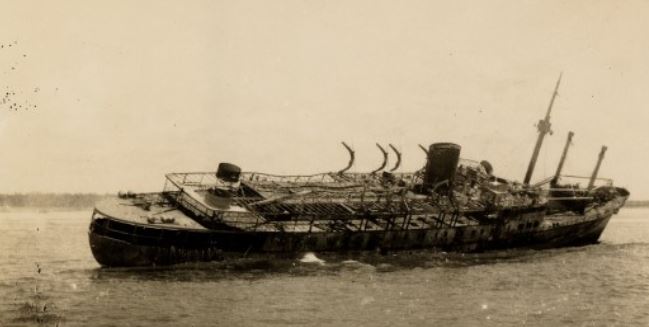

Captain Cisneros turned her around to head to safety in Australia’s northern port city of Darwin, but it was too late. The following morning, the Don Isidro found herself facing an armada of 242 Japanese aircraft on their way to attack the city. Two waves of Japanese aircraft bombed and strafed the ship about 25 miles of Bathurst Island, setting her on fire.

Eleven of the Filipino crew died in the attacks and all of the ship’s lifeboats and life rafts were destroyed. The Philippine-crewed Florence D, another blockade-runner heading out from Batavia, picked up the Don Isidro’s SOS calls. Her captain decided to carry out a rescue and steamed towards the stricken ship. Unfortunately, this also put her in the path of the Japanese bombers attacking Darwin. She was hit by two bombs and sank in minutes with the loss of three lives – two Filipinos and a rescued American airman – plus hundreds of tons of rations and millions of rounds of desperately needed ammunition. The bodies of all fourteen fatalities were never recovered.

Despite the fire, Cisneros kept the Don Isidro going in a desperate attempt to reach safety. However, the engines failed three miles offshore, forcing the survivors to jump overboard and swim the rest of the way. They reached the shore of Bathurst Island by 2 or 3 am the next day after spending up to ten hours in the water, and were rescued later in the day by an Australian ship. Several were severely burned.

Two of the casualties, a Filipino sailor and the leader of the US Army detachment, Second Lieutenant Kane, subsequently died in hospital in Darwin — Kane suffering a lingering death from gangrene. Eight of the other 14 Americans were also injured, some severely, but survived.

The Don Isidro drifted afire, unmanned and unpowered, until she beached in shallow water off Bathurst Island. She was left there as a burnt-out hulk, her vital cargo destroyed or rendered unusable. If Hubbard had not chosen to send her thousands of miles in the wrong direction and had instead used the shorter Torres Strait route — which later blockade-running ships used successfully — the vessel would never have been anywhere near the Japanese assault force, and the Florence D would not have made her ill-fated rescue attempt.

Hubbard appears to have escaped blame for the disaster, probably because responsibility was diffused between the mid-ranking Army officers who had approved his plan. He was already preparing to leave Australia when the ships were sunk and may not have heard about their fate until he returned to the US.

In the confusion that followed the bombing of Darwin — which included claims that Nazi bombers had been among the attacking force and fears that the Japanese were about to invade Australia — it is unlikely that his superiors paid much thought to the junior officer that they had kicked out of the country a week earlier.

The overall resupply operation itself was a failure. Three of the supply ships made it to the Philippines, but only a tenth of their supplies made it to their destination. Even if they had all reached the defenders, the supplies would likely have made little difference to what was militarily a lost cause.

The American-Filipino force at Bataan surrendered on April 10 and the garrison at Corregidor fell on May 6. The supplies carried by the blockade-runners would probably only have delayed defeat by a few days, even if they had all arrived on time. In other words, it would hardly have made a difference to the outcome if Hubbard had not blundered.

Nonetheless, Hubbard was evidently very concerned by the repercussions of his failures in Australia. When his friend and publisher John W. Campbell met Hubbard in Vallejo, California, not long after his return from Australia, Campbell noted that Hubbard appeared “angry, bitter, and very much afraid.”

Campbell attributed this to Hubbard fearing that he would “get assigned to some shore job, which he does not want, and kept from going to sea again.” In fact, since Hubbard had only ever had shore jobs and had never been posted to a ship, the more likely explanation is that he was afraid of the fallout from the Don Isidro affair, and was angry and bitter at the way his superiors in Australia had treated him.

The very secrecy of the operation — the full details of which have been pieced together by historians only in the last few years from fragmentary records — may well have worked in Hubbard’s favor. When he was discharged from a short hospital stay in Vallejo, he was reassigned to work in the Office of the Cable Censor in New York City.

His superior officer in New York, Captain Herbert K. Fenn, recommended that no disciplinary action should be taken despite Causey’s criticism. Causey’s cables were vague about the specific reasons for Hubbard being sent home. As the resupply operation had been run by the Army, not the Navy, it is quite likely that Fenn was not aware of its full details or Hubbard’s role.

Despite the loss of life and his personal humiliation, Hubbard later portrayed his time in Brisbane as a triumph. He boasted about the (still secret) mission to Campbell during a December 1944 dinner, telling Campbell that he “was the naval officer in charge of sending ships through to MacArthur on Bataan.”

A much later Church of Scientology account went as far as to say that “Hubbard so distinguished himself as an intelligence officer in Australia, he was thereafter known as “that fellow from down under.” The 16 people killed in the sinking of Don Isidro and Florence D would very likely have disagreed, had they been able to.

— Chris Owen

——————–

HowdyCon 2019 in Los Angeles

THURSDAY NIGHT OPPORTUNITY: This year’s HowdyCon is in Los Angeles. People tend to come in starting on Thursday, and that evening we will have a casual get-together at a watering hole. But we also want to point out that Cathy Schenkelberg’s “Squeeze My Cans” will be running at the Hollywood Fringe, and we encourage HowdyCon attendees to see her show on Thursday night, June 20. Tickets and more dates available here.

Friday night June 21 we will be having an event in a theater (like we did on Saturday night last year in Chicago). There will not be a charge to attend this event, but if you want to attend, you need to RSVP with your proprietor at tonyo94 AT gmail.

On Saturday, we are joining forces with Janis Gillham Grady, who is having a reunion in honor of the late Bill Franks. Originally, we thought this event might take place in Riverside, but instead it’s in the Los Angeles area. If you wish to attend the reunion, you will need to RSVP with Janis (janisgrady AT gmail), and there will be a small contribution she’s asking for in order to help cover her costs.

HOTEL: Janis tells us she’s worked out a deal with Hampton Inn and Suites, at 7501 North Glenoaks Blvd, Burbank, (818) 768-1106. We have a $159 nightly rate for June 19 to 22. Note: You need to ask for the “family reunion” special rate.

——————–

Scientology’s celebrities, ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and more!

We’ve been building landing pages about David Miscavige’s favorite playthings, including celebrities and ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and we’re hoping you’ll join in and help us gather as much information as we can about them. Head on over and help us with links and photos and comments.

Scientology’s celebrities, from A to Z! Find your favorite Hubbardite celeb at this index page — or suggest someone to add to the list!

Scientology’s ‘Ideal Orgs,’ from one end of the planet to the other! Help us build up pages about each these worldwide locations!

Scientology’s sneaky front groups, spreading the good news about L. Ron Hubbard while pretending to benefit society!

Scientology Lit: Books reviewed or excerpted in our weekly series. How many have you read?

——————–

THE WHOLE TRACK

[ONE year ago] Early witness Don Rogers on Hubbard and ‘prior lives’: ‘Nothing but a parlor hypnosis trick’

[TWO years ago] Danny Masterson hires Michael Jackson criminal defense attorney Tom Mesereau in rape probe

[THREE years ago] 66 years ago, L. Ron Hubbard transubstantiated from pulp writer to god among men

[FOUR years ago] Scientology answers Garcia motion: We are definitely a bona fide worldwide religion!

[FIVE years ago] Ryan Hamilton adds Colorado in new lawsuits against Scientology’s rehab network

[SIX years ago] Search Warrant: Scientology’s Atlanta Drug Rehab Billed $3 Million in Insurance Fraud

——————–

Bernie Headley has not seen his daughter Stephanie in 5,441 days.

Valerie Haney has not seen her mother Lynne in 1,570 days.

Katrina Reyes has not seen her mother Yelena in 2,074 days

Sylvia Wagner DeWall has not seen her brother Randy in 1,554 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his grandson Leo in 614 days.

Geoff Levin has not seen his son Collin and daughter Savannah in 505 days.

Christie Collbran has not seen her mother Liz King in 3,812 days.

Clarissa Adams has not seen her parents Walter and Irmin Huber in 1,680 days.

Carol Nyburg has not seen her daughter Nancy in 2,454 days.

Jamie Sorrentini Lugli has not seen her father Irving in 3,228 days.

Quailynn McDaniel has not seen her brother Sean in 2,574 days.

Dylan Gill has not seen his father Russell in 11,140 days.

Melissa Paris has not seen her father Jean-Francois in 7,060 days.

Valeska Paris has not seen her brother Raphael in 3,227 days.

Mirriam Francis has not seen her brother Ben in 2,808 days.

Claudio and Renata Lugli have not seen their son Flavio in 3,069 days.

Sara Goldberg has not seen her daughter Ashley in 2,108 days.

Lori Hodgson has not seen her son Jeremy and daughter Jessica in 1,820 days.

Marie Bilheimer has not seen her mother June in 1,346 days.

Joe Reaiche has not seen his daughter Alanna Masterson in 5,435 days

Derek Bloch has not seen his father Darren in 2,575 days.

Cindy Plahuta has not seen her daughter Kara in 2,895 days.

Roger Weller has not seen his daughter Alyssa in 7,751 days.

Claire Headley has not seen her mother Gen in 2,870 days.

Ramana Dienes-Browning has not seen her mother Jancis in 1,226 days.

Mike Rinder has not seen his son Benjamin and daughter Taryn in 5,528 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his daughter Spring in 1,634 days.

Skip Young has not seen his daughters Megan and Alexis in 2,036 days.

Mary Kahn has not seen her son Sammy in 1,908 days.

Lois Reisdorf has not seen her son Craig in 1,491 days.

Phil and Willie Jones have not seen their son Mike and daughter Emily in 1,986 days.

Mary Jane Sterne has not seen her daughter Samantha in 2,240 days.

Kate Bornstein has not seen her daughter Jessica in 13,349 days.

——————–

Posted by Tony Ortega on May 9, 2019 at 07:00

Posted by Tony Ortega on May 9, 2019 at 07:00

E-mail tips to tonyo94 AT gmail DOT com or follow us on Twitter. We also post updates at our Facebook author page. After every new story we send out an alert to our e-mail list and our FB page.

Our new book with Paulette Cooper, Battlefield Scientology: Exposing L. Ron Hubbard’s dangerous ‘religion’ is now on sale at Amazon in paperback and Kindle formats. Our book about Paulette, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology tried to destroy Paulette Cooper, is on sale at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook versions. We’ve posted photographs of Paulette and scenes from her life at a separate location. Reader Sookie put together a complete index. More information can also be found at the book’s dedicated page.

The Best of the Underground Bunker, 1995-2018 Just starting out here? We’ve picked out the most important stories we’ve covered here at the Underground Bunker (2012-2018), The Village Voice (2008-2012), New Times Los Angeles (1999-2002) and the Phoenix New Times (1995-1999)

Other links: BLOGGING DIANETICS: Reading Scientology’s founding text cover to cover | UP THE BRIDGE: Claire Headley and Bruce Hines train us as Scientologists | GETTING OUR ETHICS IN: Jefferson Hawkins explains Scientology’s system of justice | SCIENTOLOGY MYTHBUSTING: Historian Jon Atack discusses key Scientology concepts | Shelly Miscavige, ten years gone | The Lisa McPherson story told in real time | The Cathriona White stories | The Leah Remini ‘Knowledge Reports’ | Hear audio of a Scientology excommunication | Scientology’s little day care of horrors | Whatever happened to Steve Fishman? | Felony charges for Scientology’s drug rehab scam | Why Scientology digs bomb-proof vaults in the desert | PZ Myers reads L. Ron Hubbard’s “A History of Man” | Scientology’s Master Spies | The mystery of the richest Scientologist and his wayward sons | Scientology’s shocking mistreatment of the mentally ill | The Underground Bunker’s Official Theme Song | The Underground Bunker FAQ

Watch our short videos that explain Scientology’s controversies in three minutes or less…

Check your whale level at our dedicated page for status updates, or join us at the Underground Bunker’s Facebook discussion group for more frivolity.

Our non-Scientology stories: Robert Burnham Jr., the man who inscribed the universe | Notorious alt-right inspiration Kevin MacDonald and his theories about Jewish DNA | The selling of the “Phoenix Lights” | Astronomer Harlow Shapley‘s FBI file | Sex, spies, and local TV news | Battling Babe-Hounds: Ross Jeffries v. R. Don Steele