Historian Chris Owen is back with a very timely piece for us after Leah Remini once again provided so much material for debate…

One of the most common comments heard after every episode of Leah Remini’s Scientology and the Aftermath is, “Why doesn’t the government do something about it?” This isn’t a complaint that is limited to the US — Scientology has faced challenges in dozens of countries around the world. Yet it has survived nearly 70 years of criticism, lawsuits, defections, investigations, raids and scandals. How has it managed to do so?

That’s the subject of a major project that I’ve been working on for the past year, a new book exploring Scientology’s relationship with its adversaries around the world, from 1950 to the present day. It’s a project which has so far taken me through three continents and many thousands of pages of archived documents, much of which has never been reported on before. Regular Bunker readers will have seen some of the offshoots of that research on this blog during the course of the year.

(If you can, please help to support this project via my GoFundMe page!)

Scientology’s long history of facing external opposition — from governments, law enforcement agencies, and medical organisations — has left a deep mark on its structure and outlook. Its predecessor, Dianetics, collapsed in a welter of unpaid bills and lawsuits. Hubbard set about making his new Scientology organisation invulnerable to external pressure. His goal was threefold: to deflect, deter, and defeat any external opponent.

Scientology’s approach to deterring conflict has a lot in common with that of a porcupine: Look dangerous, make threatening noises, and inflict severe pain on an enemy if necessary. Governments potentially have a huge amount of power, but they are constrained by laws, regulations, and resources. (And rightly so; it’s the reason our societies don’t look like, say, China.) Scientology has found ways of leveraging the law and its opponents’ weak points to deter and defeat them.

From Scientology’s perspective, it is obviously best to avoid any issue becoming the subject of an investigation. Most problems start out locally, so a top priority for any Scientology org is to carry out what L. Ron Hubbard called “safepointing” — getting close to local politicians, police officers, and other influential figures who could cause trouble for Scientology or, alternatively, help it to avoid problems. Hubbard told Scientologists to “carefully and painstakingly find out who exactly are the top dogs in the area in financial and political circles, and their associates and connections, and to what each one is hostile … Viability [of Scientology] depends on having all areas and persons who could affect or influence the operation under PR control.” Outreach to police departments, such as in Los Angeles or Clearwater, are examples of “PRO [Public Relations Officer] Area Control” in action.

Safepointing is a continuous, carefully planned and well-resourced activity. As Hubbard himself said, “the safe point takes consideration over active defense but takes even greater consideration over delivery operations.” While it’s not unusual for organisations to engage with the wider community as part of their outreach activities, it is notable that Hubbard describes safepointing entirely in terms of protecting Scientology and makes no mention whatsoever of any benefit to society. He clearly saw it as a means of obtaining protection by cultivating powerful allies. Hubbard pursued this tactic personally during his Mediterranean voyages, wooing the political elites of Corfu and Morocco in an effort to get them on Scientology’s side.

While Scientology’s poor public image might make it seem that the church’s friendship would be a liability, it does have some significant assets. Its great wealth enables it to make large donations to causes that its allies care about, its supply of effectively free labor from its members enables it to carry out PR activities that help its allies and it can exploit its celebrity members to dazzle those it wants to get onside (as Leah Remini can probably testify). In US cities, it can make friends with the police by hiring officers to work as security guards while off duty. Scientology can, entirely legally, funnel thousands of dollars into individual officers’ pockets; it would only be human nature for those officers to feel grateful or indebted to the church as a result. Scientology can also play politics: In Greece, files seized by police from the church’s Office of Special Affairs revealed that it fed information to political opponents of its targets, much as it did in the 1980s when it collaborated with conservative groups to attack the IRS.

The behind-the-scenes nature of safepointing makes it hard to evaluate how effective it is as a tactic, but Scientology’s efforts make it clear that the church sees it as critically important. While it may be legal, safepointing can compromise the integrity of its targets. We’ve seen how the LAPD’s public credibility has been undermined by its connections with Scientology, which has raised doubts about its ability to police the church fairly in cases such as the Danny Masterson rape allegations. Interactions with Scientology can also put recipients in an ethically compromised position, if they fear consequences for their careers if they take action against their benefactors. Well-run organisations have strong and enforced ethical standards to avoid exactly this scenario.

Scientology’s outreach to other faith groups, particularly Christian churches, is another key element of safepointing. It has been working hard to convince Christian groups that its interests are the same as theirs. In the US it has been able to tap Christian groups’ fears about government or judicial interference to gain their support in key cases. When the FBI raided Scientology in 1977 to expose the church’s massive program of espionage against the US government, Christian figures protested about supposed “government persecution.” Only a few years later, when a lawsuit produced a $39 million judgment against Scientology, the church recruited Christian and Jewish allies to march alongside thousands of Scientologists in the streets of Portland, Oregon.

The 1993 decision by the IRS to grant tax exemption to Scientology gave the church an enormously important new means to build alliances with Christian groups. They probably couldn’t care less about Scientology’s bona fides as a church, but they have common interests with Scientology in maintaining their own exemptions from taxation. Some high-profile Christian groups have perpetrated at least as many abuses of tax exemption as Scientology — at least David Miscavige has never asked Scientologists to buy him a $65 million private jet. A decision by the IRS to reopen the question of Scientology’s tax exemption would likely cause concern from a wide range of Christian groups, some of which would be equally vulnerable to allegations of abuses. An actual revocation would create a firestorm of protests from religious organisations. Scientology will be well aware of this and is in a good position to enlist the support of other groups to make any such fresh investigation or revocation politically impossible.

Scientology can also count on its reputation for extreme litigiousness as a deterrent tool. In fact, Scientology is a lot less litigious now than in the past. There really was a time (in the 1960s and 1970s) when it would sue at the drop of a hat, but — likely due to David Miscavige’s aversion to court-ordered depositions — it is now relatively restrained in suing people. Instead, as many litigants have found, it grinds out litigation for years, or even decades, racking up huge legal bills for its opponents. The US government needed five years to convict Scientologists involved in the Operation Snow White espionage case; in Canada, a parallel case lasted 10 years. It took Larry Wollersheim 22 years to win his case against Scientology, while Scientology’s litigation against the Internal Revenue Service (in a series of cases) lasted over 30 years, from the late 1950s to the early 1990s. Quite apart from the financial cost, no prosecutor is likely to want their career to be dominated by years of Scientology litigation — it would be a career-ending move.

Another strand, closely linked to safepointing, is Scientology’s use of intelligence tactics and dirty tricks. The 1970s tactic of infiltrating organisations with undercover Scientologists was carried out, to a large extent, to provide early warning of legal troubles. Police departments, law firms and public prosecutors’ offices were among the key targets of Scientology’s spies. The exposure and prosecution of this activity in 1977 seems to have led to Scientology discontinuing, or at least sharply reducing, its use of its own members to carry out infiltrations.

Instead, judging by files seized from the Greek Scientology org in the 1990s, Scientology seems to have taken the far less legally risky approach of using informants and allies to obtain inside information of benefit to the church. There’s evidence that this has happened in the US as well. According to the former Scientologist Merrell Vannier, the church was tipped off about an arrest warrant against him by an LA County assistant district attorney named Marcia Clark — later famous for her role in the botched OJ Simpson prosecution. Clark wasn’t and isn’t a Scientologist, but Vannier reports that her husband at the time was a church member. Her tip-off enabled Vannier to evade arrest and flee into hiding with Scientology’s assistance.

Private investigators are also frequently employed through the law firms retained by the church. This approach is likely to shield Scientology’s legal liability if PIs are caught breaking the law. While Scientology’s PIs are often used for harassment, they have also been used to entrap and expose public officials. While as Stacy Brooks, then a senior Scientology official, has put it, “What you do with an enemy is you go after them and harass them and intimidate them and try to expose their crimes until they decide to play ball with you.” One notorious example was that of Judge Charles Richey, who was overseeing the trial of the Operation Snow White defendants until a PI working for Scientology carried out a sting operation which forced the judge’s resignation.

While Scientology was fighting for tax exemption from the IRS in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it hired private investigators to dig into the personal lives of IRS officials. One investigator interviewed by The New York Times said the church had offered him $1 million to find evidence of corruption among IRS officials. Another who worked for the church for 18 months said that, among other things, he had set up a fake news bureau, infiltrated IRS conferences, investigated properties owned by IRS officials for possible violations of building codes, surreptitiously obtained internal IRS documents and attempted to seduce a female IRS official. He provided the church with the names and phone numbers of IRS agents that he felt could be blackmailed, had a drinking problem, or were suspected of cheating on their spouses. Tenants in apartments owned by IRS officials found private investigators knocking on their doors and making allegations about their landlords. Other officials experienced strange incidents such as repeated late night calls to their unlisted numbers. The garden hoses of one assistant commissioner were repeatedly turned on at night by parties unknown, while others found their dogs and cats going missing.

While such activities shouldn’t in principle influence government decision-making, it seems clear that it did in the case of the IRS. David Miscavige himself boasted about Scientology’s “attack … impinging on their resources in a major way and our exposés of their crimes were beginning to have serious political reverberations.” As well as affecting ongoing decision-making, Scientology’s reputation for using hardball tactics is very likely a deterrent to other agencies contemplating action against the church.

Scientology’s biggest deterrent is its claim of religious status and consequent protection under the First Amendment and other freedom-of-religion legislation. Hubbard was very clear that, as he put it in 1954, Scientology was “making itself bulletproof in the eyes of the law” when it switched to calling itself a church. The strategy paid off when Scientology was able to defeat the Food and Drug Administration’s attempt to condemn E-meters as fraudulent healing devices and persuaded the courts that they were religious artifacts. The US courts recognized Scientology as a religion as early as 1983, a decade before the more famous IRS recognition. Each recognition in each new jurisdiction has been used as a stepping-stone to persuade still more jurisdictions to recognize Scientology as a religion.

Scientology’s religious recognition has given the church a powerful tool with which to shield itself from investigations and lawsuits. The FBI’s investigation into conditions at Scientology’s Gold Base in California was abandoned after it concluded that the church’s First Amendment claims meant that any prosecution was unlikely to succeed. First Amendment issues were likely the reason why no Scientology organisation was prosecuted for the Operation Snow White spying scandal, despite the fact that numerous orgs were involved. (Canada, which takes a different approach to policing faith groups, successfully prosecuted the Church of Scientology of Toronto.) Similarly, private litigation in the US has failed after courts concluded that religious protections in law meant that the government could not interfere. Decades of legislation and court rulings have effectively expanded the First Amendment into a shield that puts faith groups beyond the reach of many laws.

While other countries don’t generally have protections as sweeping as those granted in the US, it’s striking that Scientology has been able to evade state actions even in countries hostile to it. It has owed this success, to a significant extent, due to its policy of corporate decentralization. There is no single “Church of Scientology” corporately; instead, there are dozens, possibly hundreds, of legally separate entities, each effectively firewalled from the rest. The Sea Org provides the glue that holds them together, but as it is an unincorporated body with no legal identity of its own, it cannot be sued. If one of the entities suffers an adverse court judgement, the damage is limited. This policy was one of Hubbard’s key lessons from the failure of the Dianetics Foundation, which were held liable for the debts of its branches. In 1953 he wrote:

[Scientology is] of sufficient plasticity that it does not require extraordinary methods of financing and … is sufficiently dispersed to immunise it against attacks … its lack of corporate interconnection makes a would-be attacker such as the [American Medical Association] stay its hand in the face of an impossible task, for in order to “stop” Scientology such an attacker would have to sue at least twenty different places and companies in that many different locations and that would cost in legal fees alone a fortune.

France and Greece offer prime examples of how this has worked for Scientology in practice. Scientology has experienced more police raids in France than in any other country, reflecting the French government’s determination to enforce secular values. It has suffered legal defeats: a number of Scientology officials, including Hubbard himself, have been convicted of various offences over the years. Nonetheless it still has ten orgs and missions around the country. The state targeted one org, the Celebrity Centre, for dissolution but was unable to make it stick due to a coincidental change in the law. Even if it had been closed down, the other corporate entities would have been unaffected and Scientology would likely have continued as before. Greece offers an even starker example: after the Athens org, the only one in the country, was dissolved by the courts, Scientology simply transferred its assets to another newly-established entity.

A final, essential ingredient in Scientology’s strategy is its interlinked use of intelligence and public relations tactics to attack its opponents. Hubbard instructed that Scientology should not only seek to create a positive image for itself, but seek to destroy the image of its enemies. The notorious “Fair Game” tactics that the church has pursued for over 50 years rely on using intelligence methods to acquire compromising information on targets, then using that to undermine their reputations. As Hubbard put it in his 1957 Manual of Justice, Scientology should “always find or manufacture enough threat against [enemies] to cause them to sue for peace. Don’t ever defend. Always attack.” He urged the use of “black propaganda” to “destroy reputation or public belief in persons, companies or nations.”

At an individual level, such tactics are meant to deter people from criticising Scientology or obstructing its activities. At a corporate level, they are meant to put pressure on them to cooperate with Scientology or to push them to discipline employees who criticise the church. Scientology’s recent campaigning against Disney’s advertisers is a case in point: it is clearly meant to increase the reputational cost to Disney of allowing A&E to broadcast Leah Remini’s show.

The often literally unbelievable nature of Scientology’s claims may seem to be counter-productive, but it has a greater impact than might at first be appreciated. To take one recent example, it’s very unlikely that anyone who claims that Leah Remini was responsible for a murder in Sydney actually believes that. Hubbard told Scientologists to take advantage of the media’s love of sensationalism: “Start feeding lurid, blood sex crime actual evidence on the attackers to the press.” By making sensational claims, Scientology gets headlines such as “Scientology Accuses A&E, Leah Remini of Inciting Church Murder.” It’s nonsense, but it makes the headlines and gets Scientology’s claims into the public arena.

In conclusion, it’s essential to bear in mind that these tactics aren’t just used in isolation, nor are they used haphazardly. They are part of a complex, well-tested playbook of methods, honed through over half a century of experience. Scientology’s tactics and sheer persistence have made it an extremely hard target for state agencies and law enforcement organisations. Ironically, despite all the investigations, lawsuits and controversies of the last few decades, the biggest damage to Scientology has been entirely self-inflicted. The mismanagement of L. Ron Hubbard and his successor David Miscavige have caused far more lasting harm than any action taken by the state.

— Chris Owen

——————–

A reminder about Joy Villa (and her Grammy dresses)

As some of our readers predicted, Joy Villa showed up at the 2019 Grammys dressed as a wall. The barbed wire was a tacky touch, and we have to wonder if Pink Floyd will send her a cease and desist over her blatant rip-off of its trademark slogan. Ah well, the press was taken in as usual. But for those still struggling to understand what Joy is all about, we’ll offer again our short primer on her…

——————–

Start making your plans!

——————–

Scientology’s celebrities, ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and more!

We’ve been building landing pages about David Miscavige’s favorite playthings, including celebrities and ‘Ideal Orgs,’ and we’re hoping you’ll join in and help us gather as much information as we can about them. Head on over and help us with links and photos and comments.

Scientology’s celebrities, from A to Z! Find your favorite Hubbardite celeb at this index page — or suggest someone to add to the list!

Scientology’s ‘Ideal Orgs,’ from one end of the planet to the other! Help us build up pages about each these worldwide locations!

Scientology’s sneaky front groups, spreading the good news about L. Ron Hubbard while pretending to benefit society!

Scientology Lit: Books reviewed or excerpted in our weekly series. How many have you read?

——————–

THE WHOLE TRACK

[ONE year ago] Scientology targets the Red Cross in its latest sneaky front group scheme

[TWO years ago] What happens when Scientology helps you reach ‘your full potential’

[THREE years ago] The disgraced sheriff, the Holocaust survivor, and Scientology’s most unhinged front group

[FOUR years ago] These are the superpowers Scientologists are paying big bucks to attain

[FIVE years ago] It’s time to wake up our space cooties on Scientology’s New Operating Thetan Level Five!

[SIX years ago] Scientology’s “Pope” isn’t resigning, but some in the Church want to give him a push

[SEVEN years ago] Scientology Dramaturgy: Commenters of the Week!

——————–

Bernie Headley has not seen his daughter Stephanie in 5,357 days.

Valerie Haney has not seen her mother Lynne in 1,488 days.

Katrina Reyes has not seen her mother Yelena in 1,990 days

Sylvia Wagner DeWall has not seen her brother Randy in 1,470 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his grandson Leo in 533 days.

Geoff Levin has not seen his son Collin and daughter Savannah in 421 days.

Christie Collbran has not seen her mother Liz King in 3,728 days.

Clarissa Adams has not seen her parents Walter and Irmin Huber in 1,596 days.

Carol Nyburg has not seen her daughter Nancy in 2,370 days.

Jamie Sorrentini Lugli has not seen her father Irving in 3,144 days.

Quailynn McDaniel has not seen her brother Sean in 2,490 days.

Dylan Gill has not seen his father Russell in 11,056 days.

Melissa Paris has not seen her father Jean-Francois in 6,976 days.

Valeska Paris has not seen her brother Raphael in 3,143 days.

Mirriam Francis has not seen her brother Ben in 2,724 days.

Claudio and Renata Lugli have not seen their son Flavio in 2,984 days.

Sara Goldberg has not seen her daughter Ashley in 2,024 days.

Lori Hodgson has not seen her son Jeremy and daughter Jessica in 1,736 days.

Marie Bilheimer has not seen her mother June in 1,262 days.

Joe Reaiche has not seen his daughter Alanna Masterson in 5,351 days

Derek Bloch has not seen his father Darren in 2,491 days.

Cindy Plahuta has not seen her daughter Kara in 2,811 days.

Roger Weller has not seen his daughter Alyssa in 7,667 days.

Claire Headley has not seen her mother Gen in 2,786 days.

Ramana Dienes-Browning has not seen her mother Jancis in 1,142 days.

Mike Rinder has not seen his son Benjamin and daughter Taryn in 5,444 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his daughter Spring in 1,550 days.

Skip Young has not seen his daughters Megan and Alexis in 1,953 days.

Mary Kahn has not seen her son Sammy in 1,824 days.

Lois Reisdorf has not seen her son Craig in 1,407 days.

Phil and Willie Jones have not seen their son Mike and daughter Emily in 1,902 days.

Mary Jane Sterne has not seen her daughter Samantha in 2,156 days.

Kate Bornstein has not seen her daughter Jessica in 13,265 days.

——————–

Posted by Tony Ortega on February 11, 2019 at 07:00

Posted by Tony Ortega on February 11, 2019 at 07:00

E-mail tips to tonyo94 AT gmail DOT com or follow us on Twitter. We also post updates at our Facebook author page. After every new story we send out an alert to our e-mail list and our FB page.

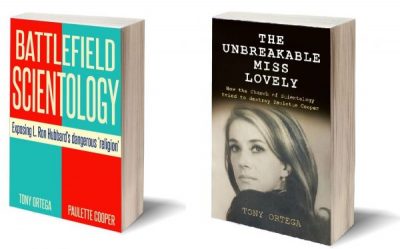

Our new book with Paulette Cooper, Battlefield Scientology: Exposing L. Ron Hubbard’s dangerous ‘religion’ is now on sale at Amazon in paperback and Kindle formats. Our book about Paulette, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology tried to destroy Paulette Cooper, is on sale at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook versions. We’ve posted photographs of Paulette and scenes from her life at a separate location. Reader Sookie put together a complete index. More information can also be found at the book’s dedicated page.

The Best of the Underground Bunker, 1995-2018 Just starting out here? We’ve picked out the most important stories we’ve covered here at the Underground Bunker (2012-2018), The Village Voice (2008-2012), New Times Los Angeles (1999-2002) and the Phoenix New Times (1995-1999)

Other links: BLOGGING DIANETICS: Reading Scientology’s founding text cover to cover | UP THE BRIDGE: Claire Headley and Bruce Hines train us as Scientologists | GETTING OUR ETHICS IN: Jefferson Hawkins explains Scientology’s system of justice | SCIENTOLOGY MYTHBUSTING: Historian Jon Atack discusses key Scientology concepts | Shelly Miscavige, ten years gone | The Lisa McPherson story told in real time | The Cathriona White stories | The Leah Remini ‘Knowledge Reports’ | Hear audio of a Scientology excommunication | Scientology’s little day care of horrors | Whatever happened to Steve Fishman? | Felony charges for Scientology’s drug rehab scam | Why Scientology digs bomb-proof vaults in the desert | PZ Myers reads L. Ron Hubbard’s “A History of Man” | Scientology’s Master Spies | The mystery of the richest Scientologist and his wayward sons | Scientology’s shocking mistreatment of the mentally ill | The Underground Bunker’s Official Theme Song | The Underground Bunker FAQ

Watch our short videos that explain Scientology’s controversies in three minutes or less…

Check your whale level at our dedicated page for status updates, or join us at the Underground Bunker’s Facebook discussion group for more frivolity.

Our non-Scientology stories: Robert Burnham Jr., the man who inscribed the universe | Notorious alt-right inspiration Kevin MacDonald and his theories about Jewish DNA | The selling of the “Phoenix Lights” | Astronomer Harlow Shapley‘s FBI file | Sex, spies, and local TV news | Battling Babe-Hounds: Ross Jeffries v. R. Don Steele