One of our favorite stories at the Village Voice was the chance we got to write about Kate Bornstein’s unique journey in Scientology and later as a well-known New York transgender performance artist, captured in the 2012 memoir, A Queer and Pleasant Danger. Kate has had an amazing year with a run on Broadway and ever-increasing fame as a gender theorist. We’re thrilled to get the chance to run this lengthy excerpt from Kate’s deliciously written book. This is chapter 11, “All Good Things,” and we’re in the 1970s as Al Bornstein, the former first mate of the flagship Apollo, had been through one marriage, to Molly, which had produced a daughter, Jessica. But now Al was alone and working around the clock for the Sea Org in New York…

Fighting the good fight in the Sea Org had made me the good guy I’d always longed to be. After a decade of 24-7 loyal active duty, I was at the top of my game. I was a full Lieutenant. Only fifty people in all of Scientology outranked me. I’d been First Mate of the Flagship; and a few years later, I was working directly with the Commodore, planning public relations strategies for Scientology worldwide. I managed an entire fucking continent for them. Then I crashed and burned on Southern Comfort and Coca-Cola, sex, junk food, and tranny porn—it’s what got me through my months-long bone-deep loneliness after Jessica left. My job performance took a nosedive and I was summarily removed from my post in middle management and demoted to sales, where, phoenix-like, I rose from my own ashes brighter and stronger than ever.

I was a terrific salesman, a natural. I’d spent my life trying to make people happy with me, and there’s nothing more happy-making than selling someone their dreams-come-true. In Scientology sales, we were taught to find a person’s “ruin”—whatever it was that was making a person’s life miserable and keeping them from achieving their goals. I could find anyone’s ruin in minutes—and in less than an hour, I’d’ve sold them thousands of dollars worth of Scientology services to handle it. I put together a crack staff, and together the six of us pulled in close to a quarter of a million dollars a week. I was a real man in every aspect of my life—and it all came down to money money money. After all, what are your dreams worth to you? How much money would you spend if that’s all it took to make your dreams come true? You needed what we had, and we needed your money—most, if not all, of it.

It was common knowledge in the Sea Org that the US government and economy could topple at any moment—splat—end of the world as we know it. That’s when we’d march in and take over. We were amassing a war chest for that day, and with that in mind L. Ron Hubbard took very little money from the Church—only the royalties on his books and a small administrative stipend on top of his room and board. Beyond that, every penny went into Church maintenance, defense, and expansion.

In Scientology, we never used the word sales. People who sell Scientology services have always gone by the more pleasant euphemism registrar, often shortened to reg. In the Sea Org, we softened the euphemism even further: I remained posted in New York City as part of the international sales team called Flag Service Consultants. We were among the most highly skilled sales people in all of Scientology, and we sold only the most expensive services—the topmost levels of Scientology, all of which were delivered solely on Flag by the most highly trained Sea Org members in the world. In the late 1970s I was pulling in an average of $20,000 a week for Flag. My personal sales figures often topped out at $50,000 to $70,000, which made me one of the Sea Org’s top income makers, which in turn gave me what they call ethics protection. In short, no one was allowed to fuck with me. My time was mine to call, and now that Jessica wasn’t in my life, there was no reason to be a man. I was a thetan, I reasoned, and as a being with no gender, I was making a rational decision to change my mind. I set off to explore being girl. First, I stopped eating.

The first three days back into anorexia are the most difficult—the hunger is painful at every level of your body, mind, and spirit, but if you can suffer through those three days, you can burst out into the other side to eat yourself one thousand calories a day or less and be damn proud of your resolve, the strength of your decision, and the pounds dropping away daily. Boys lose weight faster than girls, and within two months, I was seeing bones—that meant that my body was as close to being girl as I could be. And for the first time in my life, I had the money and freedom to buy clothes for who might possibly be pretty girl me—and it was a possibility, theoretically. For years—consciously and unconsciously—I’d been studying New York women and New York women’s fashion. I wouldn’t have been able to articulate this back then, but I was learning that no matter what the shape of your body, you can dress it to make yourself look great.

That’s New York fashion—women here know how to make themselves look great. Knowing that there were people who could master this skill/talent/survival tactic gave me hope that maybe I could learn how to do that for myself—like drag queens, one for one the most beautiful creatures of all humankind.

I had some money. I thanked my parents for the two years of support, and told them I was fine now—and I most certainly was, with 2 1⁄2 percent commission on all my sales. That netted me some serious cash. All my meals and living expenses were covered. I’d offered to send Molly and her new husband some child support for Jessica, but they declined. I don’t know anyone in the Sea Org those days who paid taxes. We were paid well below the poverty line on a weekly allowance of twelve to fifteen dollars. Not me. For the first time in years, I had some spending money.

So—I had the body for girl, and I had the money to dress me up. With Jessica gone, there was nothing to stop me from tracking down Lee G. Brewster’s Mardi Gras Boutique, the single largest source of trans porn in the world, as well as a large selection of women’s clothes in men’s sizes. Before she moved to more spacious floorspace down in the Meatpacking District, Lee ran her store out of a two-room flat on Tenth Avenue, in the mid-Fifties. By then, I was used to walking through urban war zones. I rang the buzzer. A sultry voice purred from the loudspeaker at the front door.

“Who are you lookin’ for?”

“Umm . . . Mardi Gras?”

“That’s me. Come on in.”

She buzzed me in, and I walked up the stone steps to her store. A beautiful boy stood on the landing on the fourth floor. He looked me up and down and gave me a mischievous smile.

“Honey,” he drawled, “I’ve been an FBI agent, a female impersonator, and now I’m a gay rights activist. I thought I’d seen it all, but what on earth are you wearing? That is not the uniform of anything I’m familiar with—and I’m quite familiar with men who wear uniforms.”

Gay rights? What was that? The beautiful boy’s beautiful eyes bored into mine—and then I realized he was flirting with me. Oh god, oh god, what was I doing here? Eyes cast down, I mumbled something about my uniform being merchant marine. I looked up again, and Lee’s face lost its friendliness. He’d become the professional shop boy. He had a lot of customers like me—cross-dressers who were too embarrassed to speak our desire out loud. He gave me a well-rehearsed talk.

“Store policy is if you don’t want to talk, you don’t have to. I’ve got pretty much everything you might be looking for. Don’t try anything on without asking me first, and if you don’t see your size, ask me—I’ve got girl things crammed into every corner of this place. Call me if you have any questions.” He buried his nose in a copy of Even Cowgirls Get the Blues. I was reading a copy myself at the time.

Miss Lee worked her shop out of drag. She told me later that it scared the customers. She’d begun her drag career in the ’60s, when drag queens were called female impersonators or female mimics. After the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969, Lee had defiantly proclaimed herself a drag queen and gay activist. She set up shop to cater to closet cases like me.

I walked through her shop, all Alice in Wonderland. There was trans porn of every conceivable genre. There were wigs, shoes, and makeup. There was padding for tits, ass, and hips—and there were corsets for bellies. There were racks and racks of women’s clothes, most of which fell into two styles: trashy glam and Betty Ford. Closeted cross-dressers of all generations have always modeled their fashion on America’s First Lady. The Barbara Bush years were unbearable.

I spent an hour exploring the shop, but I only bought the porn. I was living in a Sea Org dorm now, and it would be hard enough to hide the books and magazines—there was no place to stash women’s clothing, and certainly no place to put it on. So, I had the body, and I had the money to dress it up. All I needed was the space to do it in, away from any uninvited prying eyes. I wasn’t a pervert, I kept telling myself. I was a thetan, and thetans have no gender. I was just exploring my options, nothing wrong with that.

—

My good friend Dave Renard managed the Flag Service Consultant network remotely from his office at the Flag Land Base in Clearwater, Florida. By the late 1970s LRH had moved his home and office to a well-hidden, well-guarded desert ranch in Southern California. He’d surrounded himself with a great many more Commodore’s Messengers, which had grown from a unit into its own org—young David Miscavige was a member. Sea Org Headquarters—once stationed aboard the Flagship—had moved ashore to a hotel of faded glory in a sleepy town on Florida’s Gulf coast.

Dave was a good guy—laid back, unpretentious, and willing to bend the rules as long as it made his divisional statistics go up. He gave us free rein to make money however we best thought we could. Some weeks that meant sitting in my office at the FOLO in New York, but I’d discovered I could make a lot more money on the road, and I quickly became a traveling registrar. I spent two to three weeks at a time living out of hotels in Toronto, Boston, Charlotte, Washington, DC, and Miami. Out of town, my sales strategy was simple: I’d make as much money as possible for the org that was hosting me. If a sale came down to a Scientologist who would pay for services at either Flag or the local org but not both, I’d concede to the org even if that put my stats down for the week. Dave understood the investment. In Scientology management, there’s more focus on trends than there is on weekly rises or falls.

I was out in the world on my own terms. It was just me, with no reason I could think of to be a man. Alone and with my own hotel room, I took every opportunity to buy and dress in women’s clothing. I was careful to throw everything away before I left town, thus establishing for myself a life pattern of binge-and-purge cross-dressing.

I was averaging $200 to $400 a week with no expenses. I had money to spend! I took crewmates and sales prospects out drinking, out to dinner. I once took a sales prospect of mine down to the Meatpacking District to get him laid. He’d said he wouldn’t pay me a nickel while he was still a virgin. I paid for a clean hotel room, and I gave the working girl twice the amount she asked for and she smiled what felt like a real smile at me.

I bought boy clothes because I had to. Skinny at last, I had to buy myself uniforms that fit me—and no more ragtag accessories. I had the money to buy a regulation US Navy officer’s cap and gold lanyard. I paid the uniform shop to embroider the Sea Org emblem to wear on my cap. I was so well put together that when I looked in the mirror, I saw a girl dressed up in boy Navy clothes. I bought sassy-styled three-piece suits, shirts, and a couple of ties from gay boy boutiques in Greenwich Village. In the mirror, I saw a girl wearing boy clothes.

—

Christmastime in Manhattan, 1977. A knock on my office door.

“Excuse me, sir?”

I looked up from my desk. I was a young Johnny Depp in uniform, my shirtsleeves rolled up high on my arms. Standing in the doorway—halfway in, halfway out—stood a young woman in a Sea Org officer’s uniform as tasteful as my own. She was maybe in her early twenties, and she bore a regal resemblance to Princess Diana. I rose to my feet, and the lady in her appreciated the gentleman in me.

“How can I help you?”

“Sir—I’m Petty Officer Third Class Elizabeth Mayweather Reilly the Third. I’m the new Deputy Continental LRH Communicator here, and I’m doing my staff orientation checksheet. You’re Lieutenant Al Bronstein?”

“Bornstein,” I smiled. WASPS nearly always have a hard time with my name.

“Bornstein,” she repeated with no apology, fixing it into her mind. “Welcome to New York, Petty Officer Third Class Elizabeth Mayweather Reilly the Third. Wonderful name.” She blushed charmingly.

“You have a Montblanc pen, sir?”

PO3 Reilly was asking me the question from her orientation checklist. She’d joined the Sea Org a year earlier in Philadelphia, and she’d just been assigned to the FOLO. A new staff orientation checksheet is a treasure map of sorts written to familiarize yourself with your new office and crewmates. In an orientation checksheet, you’re directed to zigzag from one end of the office to another and back again. By the time you’ve completed, you’ve met and introduced yourself to every staff member—and for each staff member you’re given a question to ask and an obscure object to find.

“I do indeed have a Montblanc pen.”

She looked down at her checklist and made a mark, then she looked back up at me. Her eyes like emeralds flashed with delight, and into my office she pranced. Wow.

“The pen, sir?” She glanced around, from my desktop to the bookcase, the top of my filing cabinet. From across the room she couldn’t see much. “Where is it?”

“You’ve got to find it, Mister Reilly. That’s part of the fun.”

Pointing to my pocket, she tilted her head to one side. She couldn’t have been more Tinker Bell. It was all I could do not to gasp.

“Nope.”

“May I look around, sir?”

“You may do whatever you wish, Mister Reilly.”

She blushed—we both did. She set off to explore my office. I pretended to read a file as she circled the room. Her body was taut as a lean cat’s, her thin arms were muscular—like mine. Later, I discovered that we shared eating disorders. Hers was bulimia. She’d reached my desk, and was standing just behind me. I swear by all that’s holy to me, she smelled like a meadow on a warm, sunny day. She pointed to my in-basket, empty except for the pen.

“There it is!”

“Bingo! Now you’ve got a question for me?”

She looked down to her clipboard, then back up at me with the cutest damned frown I’d ever seen and have ever seen since.

“You’re not wearing your campaign ribbons, sir.”

“Right you are, PO3 Reilly.”

“Becky. Sir.”

“Becky.” Oh, I was hooked. Becky has the same charisma God gave Mary Tyler Moore.

I’d been sitting in my shirtsleeves. I rose, crossed the room, put on my Class A dress blue uniform jacket, and turned to face her. I swam in the attraction that poured from her eyes as she took me in—all Johnny Depp that I was. Wordlessly, she pointed to the array of campaign ribbons on my chest.

“Which one?” I laughed, shrugging my shoulders to invite her touch. She strode over unhesitatingly and laid her index finger on a blue and white ribbon with two stars.

“That’s the one.”

“And it means what, sir?”

“Al.”

“It means what, Al?”

“It means I’ve been a Flag officer for two years, Becky.”

She laughed delightedly and wrote my answer down on her checksheet. Then she came to attention and gave me a proper salute, making to leave. I didn’t answer her salute, so she stood there, hand to her forehead.

“Dinner with me, tonight, Becky?”

“I’d be delighted . . . Al.”

I took her to Max’s Kansas City, where she laughed and pointed at the queens. I told her I thought they were beautiful, but nowhere near as beautiful as she. After dinner, I hailed us a cab and we rode up to the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, where I rented us a room for the evening. Limb for limb, finger for finger, hunger for hunger, we matched each other all night long. We made each other laugh and cry and gasp. Becky was the woman I’d most wanted to become. Sex with Becky gave me a taste of what it might be like to be her.

—

My pal Dave had pulled some strings and successfully secured a transfer for Becky to my office as a Flag Service Consultant, where she and I quickly became a successful sales team. Both of us were charmers, and people kept writing us checks. Because we were technically Flag staff, we didn’t have to live in FOLO berthing. We rented ourselves an apartment out in Astoria, Queens, and worked out of our office at the FOLO on West Seventy-Fourth Street in Manhattan. I’d bought us a car for the commute—a 1979 fire-engine-red AMC Pacer. The car was low to the ground, nearly round, and had lots of windows—she was my space shuttle, and I loved her with the same madness as Toad loved his bright yellow motorcar. Becky and I had established the pattern of me going out on tour mostly on my own, while she worked in the city and followed up by phone the sales I’d put into motion weeks earlier. I’d grown my moustache back, and I put on weight—not too much. I was a big guy, but you wouldn’t call me fat. When we weren’t wearing our uniforms, Becky and I were dressing in more fashionable civvies. We argued that it made sales prospects feel more comfortable when we were out of uniform. Since our stats were up, we were given a green light to wear what we wanted to wear. Well, I wasn’t wearing everything I wanted to wear, but I didn’t feel much need or desire to cross-dress. Becky and I lived together like a pair of sisters, and that made me feel girl enough and happy.

—

April 1979, City Hall, Philadelphia. The judge glanced down at the divorce papers I handed him—the same ones Molly had sent me years earlier—and burst out laughing.

“Son, this is strictly Mexican—it’s not legal in the USA. I’m sorry, but you’re not divorced and I can’t marry you until you are.”

It was a sucker punch from the universe, and I went down. So did Becky, who was instantly on the verge of tears.

“B-b-but the wedding is this weekend,” I stuttered.

“It’s our big day,” she whispered. “Everyone who loves us is coming.” She was a waif in the storm, tears welling up in her eyes. And me, I’ve always defaulted to waif as part of my borderline personality disorder. In any case, the judge looked up from his desk at the two of us, and he caved.

“Aw, you two kids look like you were made for each other.” He scribbled something on our marriage application and checked off a couple of boxes. “I’m not going to be the one to stand in the way of your happiness.” He stood up and offered each of us a handshake across his desk. “And thank you for your service to the country.”

Ha-ha! Our uniforms had worked their unconscious glamour, just like the Old Man said they would when he designed them.

—

Becky had lied to the judge when she told him that everyone who loved us would be at the wedding—my parents didn’t come. Dad was officially retired from his medical practice—but healers never really retire. He and Mom were spending another month on an Indian reservation in New Mexico, where Dad was volunteering as a doctor.

They were living in a house made of clay—my mother and I both enjoyed nature, but we drew the line at indoor plumbing. Mom worked as his receptionist, seeing to all the paperwork. My father doctored in the only style he knew: arrogant, irascible curmudgeon.

“They called me Great White Father again,” he bragged, “every last one of ’em.” He never got the sarcasm of the title.

Mom and Dad were genuinely sorry to be missing the Philadelphia wedding—they adored Becky. My father told me over and over that she was the cutest girl he’d ever known.

“And smart, Albert. You’ve got a smart one there.”

My mother had hugged me close and whispered happily that I’d found a real lady.

“And strong, Albert. She’s a strong one.”

The wedding was held out on the Philadelphia Main Line, where Becky had grown up. It was a beautiful house—the ceremony would take place in the sculpted garden that was the backyard. Becky’s mom died when she was fourteen. She and her older sister had lived alone with her dad. Neither her dad nor her sister became Scientologists, but neither did they laugh at us. They did their best to take us seriously when we talked rapturously of civilizations across the universe and the millennia. Our friend Ron Miscavige—jazz trumpet player of some renown—performed the ceremony. His son, David Miscavige, was nineteen at the time, and according to all the lies on the Internet, he was busy worming his way into the Old Man’s good graces.

It was a lovely wedding. Alan was best man. Becky’s older sister Andi was maid of honor. We honeymooned on Cape Cod for six days of great sex, which only got better every time we did it.

Becky and I returned from our honeymoon to discover we’d been transferred from New York to the Flag Land Base in Clearwater. We were thrilled! We’d been posted as Flag Tours Registrars—we’d spend most of our time together on the road, back in the East US for sure, but we’d also be touring cities in Europe! We didn’t have that many belongings—it only took us one day to pack everything we owned into a trailer that could hitch onto the back of my little red motorcar. We drove south, a real live Sea Org power team in love.

Molly and her husband, Randy, were already living in Clearwater with Jessica and her baby brother, Christopher—whose name would later live on in my grandson. They’d been transferred from LA a few months earlier. Flag officers berthed in an old Quality Inn motel the Sea Org had bought when they first came ashore in Clearwater. The two-story motel looked like it could be the set for a massacre scene in a Quentin Tarantino film. Jessica and her family lived in adjoining rooms on the first floor. Becky and I built our nest up one flight. No, there was no massacre—well, yes, maybe there was.

Becky and I traveled for months through Rome, London, Berlin, Paris, Copenhagen, and more cities than I can remember. The tour itself was a drill: Geoff, our advance man, would arrive in town two weeks before us. He booked a hall, and promoted my talk to all area Scientologists. Each round of tours had a theme, but it boiled down to Come hear the officer from Flag tell you about the next amazing new technical breakthrough from L. Ron Hubbard! I talked to packed houses. Afterwards, I’d meet with the Scientologists for whom Geoff had already made appointments. Over the previous two weeks, he’d met with area registrars and set up the appointments for me—but only with people who would be able to write me a check for at least $5,000 for Flag, and $2,500 for the local org. Life on the road with Becky was nothing but fun for both of us. Well, there was one glitch in our happiness—I’d developed a wry neck. It makes my head tilt to the right and turn to the left. I had to hold my chin to look straight ahead. My father would call it spasmodic torticollis. I thought my neck went that way because of all the time I’d spent on the phone, cradling the receiver in my shoulder for hours at a time, managing orgs at the FOLO. Nope. I learned a few years ago that it’s called cervical dystonia, and I’ve still got it. But the pain in my neck was easy enough to ignore for all the joy we were having together on the road. Becky and I were home in Clearwater for days at a time—rarely as long a stay as a week. That’s when I got to drive Jessica to and from school.

My daughter was a tall and slender girl—and beautiful. Everyone said she had my face. Looking back at photographs now, it’s true. She did—and she loved my motorcar as much as I did. It was a twenty-minute drive to and from the school, thirty if I took back roads and drove the speed limit. We knew we didn’t have much time together, so both of us tried to make each conversation an important one.

“Daddy, what’s God?” I was ready for this one. I’d been thinking about it myself.

“Honey, God is the biggest, most good, and most everything of all.”

A long silence, then . . .

“Is Jesus God?”

“Where’d you hear that?”

“In school. Is Jesus our Lord?” Jessica was eight, maybe nine years old. She went to public school in Clearwater. Scientology hadn’t yet become the town’s largest landowner with parochial schools for Scientology children.

“If you want Jesus to be your lord, then sure.”

“Is Jesus your lord, Daddy?”

“No, punkin. Jesus and I are just good friends.”

“You’re going to hell, Daddy.”

“Yeah, well.”

—

In Europe, Scientologists wrote us checks made out to the Religious Research Foundation, a shell company that maintained a Swiss bank account that was in no way linked to the Church of Scientology. Any money we deposited would be used in the service of the Church without having to pass through any country’s tax system—it’s a common business practice used by many international organizations. Of course, L. Ron Hubbard had no connection with that Swiss account because it was vitally important to keep all his personal finances on the up-and-up so that no enemy of the Church could use any inadvertent financial glitch against him. But that was unthinkable—(a) because he was so powerful, and (b) because he had both the Sea Org and the Guardian’s Office to protect him, and we protected him fiercely.

So, life was . . . great. Thanks to my high income, I’d become a Sea Org star. Crew members actually lined up at the doors to send me off on tour, or welcome me home. It all came unraveled on a sunny autumn day in Zurich, 1982. I had just finished making a sizable deposit to the Swiss bank account. I was out on a quickie one-week tour on my own; Becky was back in Clearwater. This was my first time inside the bank’s home office. What a beautiful old place it was! The reverence for wealth was manifest in the severe architecture, lightly touched here and there with tasteful elegance.

I was waiting for the teller to return to his window with my receipts when a clerk appeared at my elbow and asked me to step inside the office of the vice president of the bank. Now, this had never happened to anyone else on my staff in all the time we’d been making deposits at this branch, so my antennae went up. I allowed the clerk to usher me in to the huge office of what very well might be a member of some vast international Swiss banking conspiracy.

An older gentleman was seated behind a desk across the room from me. Dignified, tastefully attired. I started to cross the room toward him, but this old guy gave me a big smile, all teeth. He got to his feet, came around the desk, and offered me a handshake. You must understand: for a Swiss banker, that’s an expression of true love. For a Swiss banker, that’s beta wolf.

“Mr. L. Ron Hubbard,” the old guy said to me, “the bank so appreciates your business all these years, and it’s such a pleasure to finally meet you in person.”

Oops. No, this was much more than an oops—this was a genuine oh fuck! Some SP inside the Swiss banking conspiracy had obviously broken into the files of the Religious Research Foundation and falsely linked them to the Old Man. Fuck, fuck, fuck! I took a deep breath and reminded myself that I was a far superior being to the old man—lying to him came easy.

“I’m so sorry,” I say. “But I am not this Mr. El? Hub Hubbard? of whom you speak.”

By then, we were both visibly pale. My mind was racing with worst-case scenarios—and the old guy realized that by naming me, he’d violated some strict law of Swiss banking privacy. We froze, our eyes locked in a long awkward silence. Then we each forced a laugh at the silly mistake, we said our goodbyes, and I strolled casually out of the bank.

There was no such thing as a cell phone. I walked across the city square to my hotel, where I placed a call from the pay phone in the lobby. I couldn’t trust that the phone in my room wasn’t tapped. I called a secret number and reached a telex operator in Denmark. I spoke to her guardedly, but she got what I was saying and fired a message off to Florida that there was some plot afoot that warranted investigation, and I would stand by for orders. The answer came back almost immediately: I was to travel now, now, now to Sussex, England, where the Church owned Saint Hill Manor and an estate of considerable size, with several buildings for advanced classes, as well as UK’s FOLO.

My cervical dystonia was in full bloom—my neck was stuck, turned severely to the left and tilted to the right. A bout of dystonia that strong always brought with it a series of searing headaches, the kind where that’s all you can pay attention to: the endlessness of the pain. Nevertheless, I took the next flight from Zurich to London, and the first train I could catch from London to Sussex. It was late when I arrived, and I was given a room reserved for visiting officers and missionaires. I took a few tablets of Empirin Compound and slept maybe four hours.

The next morning I reported for debrief to the guy in charge of all the Church’s European finances. I told him everything I’ve just told you, only in much more detail. For three days, I held my chin tightly so I could look at the guy while I was talking with him. Then orders came down for me to come on home on the next available flight. I was going home! I’d done a good job helping to uncover this plot against the Old Man. With the stress release, my bout with dystonia slowly wound down and I slept in fits and starts on the overnight flight back to the States.

As I stepped off the plane in Tampa, I was met at the gate by seven tall, muscular young guys in Sea Org officer uniforms. Heh. I was still the superstar. But it did strike me as odd that I didn’t recognize any of these officers, and I knew personally every senior officer in the Sea Org. The young men had serious faces—they told me they were members of the newly formed Financial Police. I’d never heard of that.

“What’s going on here . . . sir?”

“You’ll find out, and don’t speak unless you’re spoken to, mister.”

“Yessir.”

One for one, they outranked me, so there was no questioning their authority. We drove back to Sea Org headquarters in silence. My neck was again throbbing and threatening to wrench itself around to the left. A migraine-like headache was just beginning to break through the surface of my consciousness. All I wanted to do was get in bed with Becky—she knew how to hold my head just so. But straight away, these guys escorted me into a cold, damp hallway in the basement of the Fort Harrison Hotel. Two of the Financial Police sat me down on a metal folding chair, then took up more comfortable chairs for themselves on either side of me. I couldn’t say a word—I still hadn’t been spoken to.

After three hours, the other five officers showed up—showered, freshly shaven. I smelled sour to myself and I had a five o’clock shadow that rivaled Richard M. Nixon’s. The seven officers escorted me down the hall into a room set up with a table and an e-meter. Now, mostly when you’re audited, you’re in a small room with one other person, the auditor. There’s never more than the two of you. But now, one member of the Financial Police sits across from me, operating the meter. Two big guys are standing behind him, two more big guys stand behind me, and one more big guy stands at the door. Years later, I’d find out they call it a gang-bang sec check. One of them spoke.

“How long have you been an agent for a foreign government?”

“What the fuck?”

“Thank you,” says the big guy across from me.

Now, he didn’t say thank you because I’d told him anything he felt grateful for. He said thank you because in Scientology you’re supposed to verbally acknowledge anything that anyone says to you. You use words that show you’ve heard the other person—Thank you, OK, Good, Very Good, and so on—words that show you’ve heard the other person. It’s actually quite a civilized way to talk with people, letting them know you heard them. So he says Thank you, then a guy behind me says,

“How long have you been a drug addict?”

“What?!” I turned too quickly to face the guy and blinded myself with a bolt of pain.

“Good.”

And now I’m going to paraphrase the real honest-to-goodness questions fired at me, over and over for six hours:

Have you ever embezzled money?

I thought to myself, y’know, I never did—it never crossed my mind—and even if I’d wanted to, Scientology finance procedures were foolproof and they would’ve found me out simply by the paperwork. Was my 2 1⁄2 percent commission embezzlement?

Are you now or have you ever been a drug addict?

Ever? Was I addicted to Empirin Compound? In college, I chain-smoked marijuana and drank beer. But they knew that about me already, and I’d completed my Scientology counseling on drugs—so I was free from their harmful effects, and free from the need to take them. That made me not an addict. I answered no, and the needle on the e-meter agreed with my call.

Have you ever bombed anything?

Goodness gracious no. Skipper Bush and I once threw cherry bombs into a construction site dirt pit late at night. Did that count? No read on the meter.

Have you ever murdered anyone?

Nope. Haven’t ever had to.

Have you ever raped anyone?

Nope. Haven’t ever had to.

Have you ever had anything to do with a baby farm?

To this day, I’m not sure what they meant by baby farm, and I’ve been too timid to give it a google.

Do you collect sexual objects?

I answered that no, I don’t—which was technically correct. Two days earlier, I’d thrown out my most recent collection of tranny porn before I flew from Zurich to London.

Thank you. Do you have a secret you are afraid I’ll find out?

I was beginning to wish I’d kept some of the secrets I’d revealed in counseling sessions over the last twelve years. Once you leave, all that confidential information is fair game for the Church to use against you. Nah, they knew all my secrets. The meter kept verifying that I was clean as a whistle. And then . . .

Are you upset by this security check?

“You’re goddamn right I’m upset about this security check.”

Thank you.

Well, that led to a two-hour trail of related questions only to discover that I was upset by the security check because I’d done nothing wrong.

“Have you ever had unkind thoughts about L. Ron Hubbard?”

“Not a one,” I answered. “Ever.” But why wasn’t he personally pinning a medal on my chest for pulling his ass out of the financial fires? Unless the Swiss account actually did belong to him, in which case . . .

“OK. That read on the meter. I’ll repeat the question: Have you ever had unkind thoughts about L. Ron Hubbard?”

“Not unless you’re telling me that the Religious Research Foundation is a bank account that funnels money into the Old Man’s pockets. Is that what you’re telling me?”

“Good. Have you ever had unkind thoughts about L. Ron Hubbard?”

For two more hours, they quizzed me about all the possible un-kind thoughts I could ever have had about L. Ron Hubbard, until the meter convinced them I was OK on that score.

“Thank you. How long have you been a spy for a foreign government?”

“I am not a spy, I’m tellin’ you. I’ve been a loyal officer for twelve fucking years.”

“OK. What enemy group are you working for?”

And they kept asking me those kinds of questions for a total of six hours, carefully watching the e-meter for any signs that might reveal my evil deeds. Six hours, no evil deeds. Finally, the guy across from me played his ace. He said I’ve got a choice: I can do three years of hard physical labor, sleeping a maximum of six hours a night on a cold cement floor, eating only table scraps, and talking only with other bad people like me who were relegated to the months-old Rehabilitation Project Force. I could either do that, he said, or I could leave and be excommunicated from the Church of Scientology for the remainder of all my lifetimes ahead of me. The young officer told me that he’s going to live into the future as a hero.

“Without Scientology, you are gonna degrade into a mindless slug of a spiritual being. You’re gonna be a body thetan, attached to the toe of some street bum.”

So help me, that’s what he said. I didn’t thank him for saying it. It had been twelve years since I failed to acknowledge something another person said to me. I’d been holding the cans for six hours—you can’t ever let go of them. That meant I couldn’t hold my head straight, and my dystonia had once again begun to twist my head painfully over my left shoulder—a move that this guy interpreted as my not being able to look him in the eye.

Twelve years.

What was he saying? Sleeping on a cement floor with this neck? And he never answered my question about the Old Man and the Swiss bank account.

Twelve years.

It had to be true. Daddy was a liar and a cheat—I could deal with everything else about Scientology but that. My mind shattered like a plate glass window in a Mack Sennett comedy.

“You excommunicate me,” I said, and so they did.

—

I was packed up and gone within four hours. I wasn’t allowed to say goodbye to anyone, and if anyone spoke to me, they’d run the risk of being assigned to the Rehabilitation Project Force themselves—even my nine-year-old daughter—because they had a Rehabilitation Project Force set up especially for kids. So I never said goodbye to Jessica. I left her with Molly and Randy. They loved her, and she loved them—they’d give her love, shelter, and food.

I walked across town and a couple of miles down the highway to a truck rental office in a strip mall. I wanted a small van, but the only vehicle available for an interstate one-way trip was a fourteen-foot cargo truck. I pulled into the Quality Inn parking lot just as Becky was leaving our room. I jumped down out of the truck’s cab as she ran down the flight of stairs—we stopped just short of touching each other. She was crying. They’d already told her . . . something.

I handed her the keys to the Pacer.

“The car’s yours.”

“Al.”

“Shhhh. We can’t talk.”

She ducked her head and strode quickly away across the parking lot and around the corner, back to work. I loaded all my belongings into the truck in four quick trips, climbed back up into the cab, pulled out of the parking lot, and drove north.

After twelve years of living in a Scientologist’s idea of heaven, there I was . . . out here in hell with you. The only difference was I knew for sure it was Hell, and I knew for sure I belonged here.

— Kate Bornstein

——————–

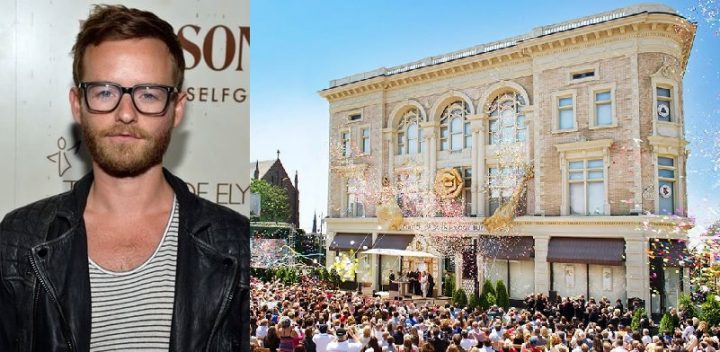

Scientology’s celebrities and ‘Ideal Orgs’ — now with comments!

We’re building landing pages about two of David Miscavige’s favorite playthings, his celebrities and his ‘Ideal Orgs.’ We’re posting pages each day, and we’re hoping you’ll join in and help us gather as much information as we can about them, in order to build a record and maintain a watch as Scientology continues its inexorable decline — and yes, we finally have comments working on these new pages! Head on over and help us with links and photos and comments about all of your favorite celebrities and failing Ideal Orgs

Previously, we posted pages for celebrities Anne Archer, Beck Hansen, Catherine Bell, Chick Corea, Elisabeth Moss, Erika Christensen, Ethan Suplee, Giovanni Ribisi, Greta Van Susteren, Jenna Elfman, John Travolta, Juliette Lewis, Kelly Preston, Kirstie Alley, Laura Prepon, Marisol Nichols, Michael Peña, Nancy Cartwright, Tom Cruise Danny Masterson, Stanley Clarke, Edgar Winter, Alanna Masterson, Billy Sheehan, Judy Norton-Taylor, Terry Jastrow, Eddie Deezen, Sofia Milos, Bodhi Elfman, Rebecca Minkoff, and Doug E. Fresh. And for the Ideal Orgs of Portland, Oregon; Sydney, Australia; San Diego, California; Denver, Colorado; Nashville, Tennessee; Perth, Australia; Tokyo, Japan; Sacramento, California; Las Vegas, Nevada; Silicon Valley, California; Rome, Italy; Orlando, Florida; Moscow, Russia; Amsterdam, Netherlands; Seattle, Washington; Dallas, Texas; Melbourne, Australia; San Fernando Valley, California; Pasadena, California; Bogotá, Colombia; Budapest, Hungary; Phoenix, Arizona; London, England; Orange County, California; Atlanta, Georgia; Auckland, New Zealand; Miami, Florida; Basel, Switzerland; Berlin, Germany; Birmingham, England; and Brussels, Belgium.

Today it’s Christopher Masterson and Buffalo, New York!

——————–

Coming November 1

Paulette tells us we can reveal the publication date she has set. We’ll let you know when pre-ordering begins.

——————–

Bernie Headley has not seen his daughter Stephanie in 5,236 days.

Katrina Reyes has not seen her mother Yelena in 1,869 days

Brian Sheen has not seen his grandson Leo in 412 days.

Geoff Levin has not seen his son Collin and daughter Savannah in 300 days.

Clarissa Adams has not seen her parents Walter and Irmin Huber in 1,475 days.

Carol Nyburg has not seen her daughter Nancy in 2,249 days.

Jamie Sorrentini Lugli has not seen her father Irving in 3,023 days.

Quailynn McDaniel has not seen her brother Sean in 2,369 days.

Dylan Gill has not seen his father Russell in 10,935 days.

Mirriam Francis has not seen her brother Ben in 2,603 days.

Claudio and Renata Lugli have not seen their son Flavio in 2,863 days.

Sara Goldberg has not seen her daughter Ashley in 1,903 days.

Lori Hodgson has not seen her son Jeremy and daughter Jessica in 1,615 days.

Marie Bilheimer has not seen her mother June in 1,141 days.

Joe Reaiche has not seen his daughter Alanna Masterson in 5,230 days

Derek Bloch has not seen his father Darren in 2,370 days.

Cindy Plahuta has not seen her daughter Kara in 2,690 days.

Roger Weller has not seen his daughter Alyssa in 7,546 days.

Claire Headley has not seen her mother Gen in 2,665 days.

Ramana Dienes-Browning has not seen her mother Jancis in 1,021 days.

Mike Rinder has not seen his son Benjamin and daughter Taryn in 5,323 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his daughter Spring in 1,429 days.

Skip Young has not seen his daughters Megan and Alexis in 1,832 days.

Mary Kahn has not seen her son Sammy in 1,703 days.

Lois Reisdorf has not seen her son Craig in 1,286 days.

Phil and Willie Jones have not seen their son Mike and daughter Emily in 1,791 days.

Mary Jane Sterne has not seen her daughter Samantha in 2,035 days.

Kate Bornstein has not seen her daughter Jessica in 13,144 days.

——————–

Posted by Tony Ortega on October 13, 2018 at 07:00

Posted by Tony Ortega on October 13, 2018 at 07:00

E-mail tips and story ideas to tonyo94 AT gmail DOT com or follow us on Twitter. We post behind-the-scenes updates at our Facebook author page. After every new story we send out an alert to our e-mail list and our FB page.

Our book, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology tried to destroy Paulette Cooper, is on sale at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook versions. We’ve posted photographs of Paulette and scenes from her life at a separate location. Reader Sookie put together a complete index. More information can also be found at the book’s dedicated page.

The Best of the Underground Bunker, 1995-2017 Just starting out here? We’ve picked out the most important stories we’ve covered here at the Undergound Bunker (2012-2017), The Village Voice (2008-2012), New Times Los Angeles (1999-2002) and the Phoenix New Times (1995-1999)

Learn about Scientology with our numerous series with experts…

BLOGGING DIANETICS: We read Scientology’s founding text cover to cover with the help of L.A. attorney and former church member Vance Woodward

UP THE BRIDGE: Claire Headley and Bruce Hines train us as Scientologists

GETTING OUR ETHICS IN: Jefferson Hawkins explains Scientology’s system of justice

SCIENTOLOGY MYTHBUSTING: Historian Jon Atack discusses key Scientology concepts

Other links: Shelly Miscavige, ten years gone | The Lisa McPherson story told in real time | The Cathriona White stories | The Leah Remini ‘Knowledge Reports’ | Hear audio of a Scientology excommunication | Scientology’s little day care of horrors | Whatever happened to Steve Fishman? | Felony charges for Scientology’s drug rehab scam | Why Scientology digs bomb-proof vaults in the desert | PZ Myers reads L. Ron Hubbard’s “A History of Man” | Scientology’s Master Spies | The mystery of the richest Scientologist and his wayward sons | Scientology’s shocking mistreatment of the mentally ill | The Underground Bunker’s Official Theme Song | The Underground Bunker FAQ

Watch our short videos that explain Scientology’s controversies in three minutes or less…

Check your whale level at our dedicated page for status updates

Join us at the Underground Bunker’s Facebook discussion group for more frivolity.

Our non-Scientology stories: Robert Burnham Jr., the man who inscribed the universe | Notorious alt-right inspiration Kevin MacDonald and his theories about Jewish DNA | The selling of the “Phoenix Lights” | Astronomer Harlow Shapley‘s FBI file | Sex, spies, and local TV news