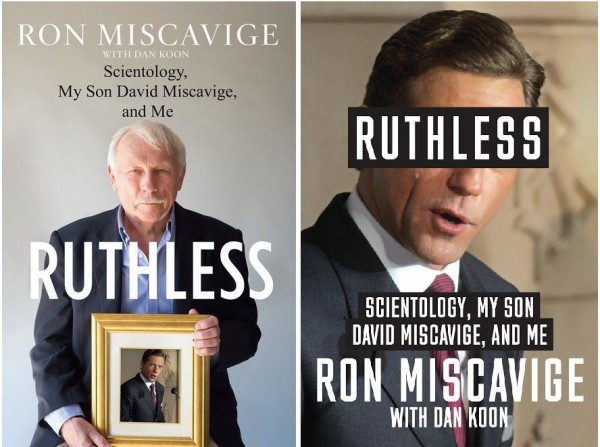

We have another treat for you in our ‘Scientology Lit’ series. Ron Miscavige has generously allowed us to post an entire chapter from his book Ruthless: Scientology, My Son David Miscavige, and Me, which he wrote with Dan Koon. Ron sent us the key chapter when he and his wife, Becky Bigelow, finally made their escape from Scientology’s Int Base which was run by Ron’s son, Scientology supreme leader David Miscavige…

When I reflect on it, the watershed moment occurred back on that August 1990 afternoon when the rain poured down and mud slid off the mountain across State Route 79 and onto base property. People busted their butts in their summer uniforms, which were all white, mind you, to protect the property from water and mudslide damage. By dinnertime, there was no one in Gold whose uniform was not soiled with mud.

Because Gold was responsible for the physical base itself, David pinned the blame for the event squarely on the shoulders of every staff member at Gold. And people bought it. Maybe some did not, and maybe some thought that what he was raving about was crazy but realized it would be prudent to act on his demands.

From that day on, things never got better. Literally, never got better. There might have been the rare good day but never a period of a week or a month when staff could breathe a sigh of relief and think, We’re OK again. We’re trusted. Never again were we in a position of trust. The attitude expressed — and that attitude came straight from David and filtered down to Gold — is that we could not be counted on to initiate anything of worth or contribute to Scientology’s purpose of making a better world. Imagine working in an environment such as that month after month, year after year.

So that you, the reader, understand, Scientology provides ways to deal with the situations that life throws at you. One of these tools is called the conditions formulas. A condition is simply a state of existence. Everything in the universe, including each of us, is in one condition or another. It might be good or it might be bad; that is beside the point. The theory behind the formulas that Hubbard developed is that one can take steps to change the condition one is in, whatever that may be, and improve it. If a person or a group determines what condition they are in, they can improve their lot by following the steps of the appropriate formula, and, sooner or later, things will improve. Except for Gold. We could not get an approval to move from one condition to the next higher one, no matter what we did or how long we worked at it. There was no forgiveness. It was like the sign over hell in Dante’s Divine Comedy: “All hope abandon, ye who enter here.”

As the years went by, that is how I began to feel. Without hope. We were never going to get out of that bad condition. When people are hopeless and held together as a group, people begin yelling and screaming at each other, and physical fights break out with people punched and thrown to the ground. Other people become apathetic and resigned: “Well, this is how I’m going to live for the rest of my days.”

I could not give up hope and that was mainly due to Becky’s imploring me, “It’s going to get better. I know it.” She is an incurable optimist and convinced me to stay. Maybe she’s right, I thought. Maybe I’m taking everything too seriously.

It never got better.

Instead it got slightly worse, bit by bit, and year by year. If something is continually becoming slightly worse, it isn’t going to start getting better unless you do something different. Either you have to change the way you are living or get out of there.

After the year 2000, regularly scheduled days off no longer existed. I did not have a day off for the next 12 years. Sea Org policy mandates that a person receive a day of liberty every two weeks. That became a dim memory at Gold. Each year every Sea Org member is supposed to have three weeks of leave. I could not get a leave to see my grandson get married. That was a real backbreaker for me. Then I could not get a leave to visit my brother when his wife died. That turned out to have been my last opportunity to see my brother alive. The next time I saw him, he was in a coffin. When my nephew called to tell me my brother had died, another Gold staff member was listening in on an extension in the same room. Everyone was subjected to these invasions of privacy, so you didn’t even think about it. It was normal.

To attend my brother’s funeral, I had to be accompanied by two “minders” plus an armed private investigator. The two minders were Greg Wilhere and Marion Pouw. My son Ronnie and his wife, Bitty, also were at the funeral, but Greg and Marion effectively prevented me from talking to them because they had left Scientology several years earlier. When that happened, I began thinking, Something really bad is going on here. Becky and I absolutely need to get out.

For many years we lived in apartments in Hemet about seven miles from the base. I told Becky, “We’ve got to get out of here and soon.” Living quarters were being built at the compound itself behind the razor wire fences, and I felt that if we were going to leave, we would have to do it before staff moved into the on-base housing. We could have filled our car at the Hemet apartment and driven off. But Becky did not want to go. She still felt that things would improve. So we moved onto the base with the rest of Gold. This was in 2006. Razor wire, guards, and surveillance cameras — you may think that I am describing a prison. No, I am simply telling you what it was like while we were living at the international headquarters of the Church of Scientology.

As with everything else, the hypersecurity was gradually ramped up through the years. When the property was first purchased, the place was wide open; you could walk from one side of the property to the other at any point along the highway. As the facility became more developed, more security measures were added, again, a little at a time. A security force was put in place. Then fences. Then gates that were operated from the main guard booth. Then motion sensors on the fences. Then razor wire on top of the fences. Then cameras to watch cars along the highway. Then a lookout station halfway up the mountain in back of the property to keep watch. And it went on like that.

The housing on the base was well designed, functional and attractive. In fact, all the facilities on the base are top notch. The problem with perfection arises when living beings actually use the facilities. The beautiful homes you see profiled in Architectural Digest have been spit-shined for a photo shoot. David apparently thought that the housing on base should always be similarly pristine. So residents had to abide by various restrictions: you could not bring food or even coffee into your room, much less have your own little fridge or coffeemaker. You couldn’t have televisions or DVD players. Each building had a commons room with a TV , but I never saw anybody watching it. People were too tired to do anything but to go to bed when they got home. If somebody did sit down to watch something on television, someone would have reported them for doing so when they should be sleeping. The TVs sat there idle, except maybe during Christmas or New Year’s, when people had a few hours of free time.

A perfect living space was one that contained no personal items such as family photos, knick-knacks or a painting on the wall. The closets were built to hold only your uniforms and a few items of personal clothing. Each room had a bathroom, but unmarried people lived in dorms with six to a room, and I imagine things got pretty crowded in the mornings. In short, the living quarters were planned around the idea of the more sterile the better. But people had personal items nonetheless. Becky and I probably had more stuff than most, and we crammed it into every shelf space and corner.

A typical day at Gold went like this: breakfast in the dining hall was at 9:00 a.m., followed at 9:30 by the first of the day’s roll calls. If you tried to grab a little extra sleep because you had been up late the night before, you would hustle down to breakfast, gulp it down and scurry out to muster. Breakfast was the same thing day in and day out: eggs, toast, granola, sometimes fruit. After eggs have been sitting in a serving pan for some time, they become cold. One day I walked into the galley and requested a couple of eggs hot off the griddle. I told the cook that I don’t like cold eggs, and all the eggs on the line were cold. “Sorry,” the cook replied, “it’s against regulations.” That’s the level of control (and insanity) that permeated the place. Anything to make a person’s life more miserable.

At morning muster, all hands were accounted for; security was supposed to find anybody who was missing. After listening to any important announcements, people hustled through the tunnel that ran underneath the highway and up to the course room for study time, which lasted until noon. During this time, people were supposed to be free to avail themselves of studies in Scientology. Mostly, though, people only studied materials designed to make them more productive in their jobs. The group and its needs always came first.

At noon, you hustled down to lunch. The meal was put out on serving carts, and you grabbed a plate, silverware and a glass, filled your plate and sat down at your table with about six or seven others. At the end of the meal, you cleaned off and stacked your dishes and then — hey, what do you know! — another muster at 12:30. More roll calls, more announcements and then it was off to work for the afternoon. Dinner was at 5:00 p.m., followed by — what else? — another muster at 5:30. Then back to work until midnight, so long as we had no emergency to deal with or an upcoming event nightmare. At those times, any semblance of a schedule went out the window. Becky, who was working in marketing, would often be awakened in the middle of the night to go back in to the office and deal with something.

That was the schedule day after day. It was a pretty gray way to live for years on end.

By this time, 2006, we knew that at some point we would leave. For the next five or six years, we lived with the knowledge that someone would become aware of what Becky and I had talked about; if that happened, the chances of our ever leaving would have been exactly zero. As the father of COB, I would have had a guard on me around the clock all year long. The opportunities for someone to learn what we talked about were numerous because staff are given “security checks” for purposes of discovering any transgressions against the group, breaking of rules, and such. Secretly planning to leave certainly qualified. A security check is Scientology’s version of an interrogation. Hubbard thought that an auditor using the E-meter would be effective in discovering whether a person was withholding knowledge of plots against him or the organization, and “sec checking” became a staple of church policy. After David took control of the church, security checks became more intense affairs with sometimes several people interrogating a suspect at the same time. When I look back on it, it reminds me of stories I heard of the Stasi in East Germany. Needless to say, our conversations were never far from our thoughts, yet Becky and I managed to keep our plans to ourselves during all that time.

In late 2011, I called David and told him, “I’ve got to see you.” He was not on the base at the time, but when he got back he arranged to see me. “Listen,” I began, “you’ve got to get me out of the music department. I’ve been writing music every day, seven days a week, month after month, and none of it is getting approved. I am living a life of failure every day. I’ll take a job waxing cars in the motorpool, or if you want to send me to Flag, I’ll work there. But I can’t live this way.”

“I’ll check it out,” he promised.

Here is what had me in such desperate straits. I did my first paid job as a musician at age 13. I spent my time in the Marines studying music and playing in the Marine band. I played professionally for years, had a recording contract with Polydor Records and a writer’s contract with Chappell Publishing. I ran the music department at Gold for many years.

Then a new person took over as music manager. Suddenly, anything I did became worthless, of no value, was not going to work and was deemed not suitable for any product. Each day I went to work, worked all day writing music, and each day it was, “Nah, it’s dated,” “It’s trite,” “It has no flavor,” “You don’t hold my attention at all,” or (sarcastically) “Oh, I didn’t know we were doing a period piece.” Yet everything he did was wonderful. He even said to me once, “Your stuff doesn’t stand up to mine in the least.”

Imagine working at a job month after month and nothing you do is considered acceptable, whereas for years and years previously, almost everything was. You can understand why I pleaded with David to check it out.

He never checked it out.

Shortly thereafter I told Becky in no uncertain terms, “We’re getting out of here.”

“OK, we’ll do it.”

We started planning our departure. One concern was how we could take all our stuff with us. We didn’t want to leave valuable things behind. At the same time, we knew we were going to leave. A little background is in order here. On my birthday the previous year, Becky arranged for my daughters, Denise and Lori, to send me a bunch of little gifts. The idea was to present me with 75 gifts for my seventy-fifth birthday. Just before my birthday, five boxes of stuff arrived from Becky, Denise and Lori. All were small gifts, like a pen or a little voice recorder.

The security guards obviously knew about this because all mail and packages were opened before being delivered. Talk about a violation of federal postal regulations, not to mention human rights! This gave Becky an idea. Her mother’s seventieth birthday was coming up, so she called her mom and told her that we were going to be sending her some stuff for her birthday. We were going to send her 70 “gifts.” Unbelievably, Becky’s plan worked. We mailed my mother-in-law my Scientology books and volumes of Hubbard’s bulletins and policy letters. I did not want to leave those behind. They contained all the writings that I had found of such value for more than 40 years, and they meant a lot to me. The philosophy was one thing; life in the Sea Org was quite another. We mailed her a car-detailing kit. The security guards who checked every piece of outgoing mail never suspected what we were doing. We sent her a ton of stuff because we knew that we could not cram everything into our Ford Focus station wagon. That these security guards fell for our ruse does not speak highly of their intelligence. Becky’s mom has never been involved with Scientology, yet we were sending her “gifts” of all of L. Ron Hubbard’s bulletin and policy letter volumes about Scientology, more than 20 thick volumes. By the time her mother’s birthday came and went, we still had not mailed everything we wanted, so we changed the story to “we are sending you Mother’s Day gifts.”

Because staff members were not allowed to have refrigerators, Becky and I would drive across the highway to the music studio, which had a refrigerator, every Sunday at 9:00 a.m. during the weekly period scheduled for cleaning and doing laundry. We would eat some cheese and salami or something. When we drove back to the housing complex area, I handed the guards some of my food, which they always appreciated. Feeding the watchdogs, you might say. It became a Sunday morning ritual as a way of getting them accustomed to what we were doing. I had a couple of other things going for us as I worked out our plan. I was 76 years old. I was the father of the leader of the church. Nobody would suspect I was trying to escape at my age.

In an ironic turn of events, beginning in January 2012, David began showing up outside MCI around the time of Gold’s evening musters. He’d wait until muster was over and then come visit with Becky and me for ten or fifteen minutes. We would shoot the breeze, laugh about stuff and reminisce about funny times. Sometimes he would grab us before muster, and we would be laughing about something while standing around the corner from the muster, and his secretary Laurisse would be trying to hush us so we wouldn’t disturb the muster. It had been years since David had visited us like that. All the while, Becky and I knew we would soon be gone.

By late March 2012, I was getting nervous. “What if we get caught? What if the guard doesn’t let us out the gate?” I’m not the nervous type, but, yeah, I was really nervous about what lay just ahead. We were going to leave the following Sunday morning, March 25. The day before, I gassed up the car in the motor pool. We had most everything packed up in our apartment. That night after work I began moving stuff out to the car. We had all our shoes in a mesh bag. As luck would have it, one of the security guards happened by on his motorcycle as I going out to the car.

“Hey, Sal, how ya doing?” I said, forcing a cheerful smile and hoping he wouldn’t notice the beads of flop sweat that instantly appeared on my forehead.

“Hey, Ronnie. Going good,” he replied. We shot the breeze for a bit before he rode off. That was a close call. He never connected the bag of shoes in my hands to anything suspicious. Sal, a close friend, could not in his wildest dreams imagine that I was loading personal effects into my car in preparation for an escape.

I went back inside, got a bag of clothes and came back out. Norman Starkey was going into the laundry room, which was right in front of my car. Norm was the trustee of L. Ron Hubbard’s estate and one of the longest-serving and most legendary Sea Org members, since reduced by David’s abuse to a shell of his formerly dynamic self.

“Hi, Ron. How’s it going?”

“Good, man.” I put the clothes in the car.

By the time I finished, the backseat was filled almost to the top. I had my horns in there. I had my Exer-Genies in there. (The Exer-Genie is an exercise device I have used for more than 50 years, the best little machine I have ever come across.) We jammed in everything we could. The next morning we got up at seven. I took my cell phone and put it aside. Same with my pager. Because we were up so early, we had nearly two hours to pace around the room, check and recheck our list of everything we needed to have, and to worry. I had a little notebook with lists of everything we were going to take and what we were going to leave. Our car only held so much, so we had to decide what to sacrifice.

I must have checked my list 50 times if I checked it once. At 8:50 we took a deep breath, closed the door to our room behind us for (we hoped) the final time and walked out to the car. I started the engine, released the parking brake, put the car in reverse and backed out of my spot. Each moment, every action, was in sharp focus as if time had slowed to a standstill. I tried to look calm, but the butterfly effect was beating my insides to a pulp as we prepared to escape.

Only two security guards were on duty on Sunday mornings. One was in the main guard booth and the other in what was called the chase car, for dealing with people coming onto the property who should not be there as well as for chasing staff members who were attempting to escape. I drove slowly past the dining area and saw the chase car parked nearby, so we knew the guard was inside eating breakfast. The other guard was in the main booth. I drove up to the West Gate, which is 200 yards west of the main booth. Here goes nothing, I thought. If he calls me up to the booth, we’re sunk. Jesus Christ, what if he doesn’t open the gate? He’s got to open the gate. Briefly, the rest of my life flashed before my eyes. I firmly believe that, had we been caught, Becky and I would have been locked up in a remote part of the base under 24-hour guard, and I would have spent the rest of my life like that. I never would have gotten out. Never.

My finger was shaking as I pressed the intercom buzzer to let him think I was going across the highway to the music studio, just as we did every Sunday morning at that time. He didn’t even answer, just opened the gate. I inched the car through and out onto the road.

“Becky, we’re turning left!”

I punched the gas and we peeled off down the highway, away from the base. I knew the guard would call me on my cell phone, which I had conveniently left in our room. “Hey, Ron, what are you doing? What’s up? Hey, Ron! Answer me!” Then he would call the chase car guard from breakfast and say, “Hey, get up here to the booth, pronto!”

Meanwhile, I was hauling ass down the road. I knew that by the time the chase car got to the booth, I would be at an intersection a mile from the base, which meant I could take any of three routes. Turning right would take me to Interstate 10. Going straight led to U.S. Route 60 toward Los Angeles. Turning left would take us toward town.I turned left, figuring that the chase car would think I was headed for a major highway.

I turned right at the first stoplight, which put us out in the boondocks. We followed that road until we came to Interstate 215.

We had made it. We were free.

— Ron Miscavige

——————–

Oklahoma, where Scientology never gets a scratch

After the state of Oklahoma failed to do a thing about the deaths of three patients in a nine-month period at Scientology’s flagship drug rehab “Narconon” facility, and then buried a report by an inspector general that called for the closing of the facility over horrific conditions (and then fired the inspector general), please excuse our lack of excitement about the news that the state’s Department of Labor is investigating the claim of a former Narconon security guard that they were shorted $420 in pay.

Yeah, Oklahoma has Scientology right were it wants now.

——————–

MEANWHILE, AT FACEBOOK…

Please join us at the Underground Bunker’s Facebook discussion group for more frivolity.

——————–

Bernie Headley has not seen his daughter Stephanie in 5,196 days.

Katrina Reyes has not seen her mother Yelena in 1,799 days

Brian Sheen has not seen his grandson Leo in 342 days.

Geoff Levin has not seen his son Collin and daughter Savannah in 230 days.

Clarissa Adams has not seen her parents Walter and Irmin Huber in 1,405 days.

Carol Nyburg has not seen her daughter Nancy in 2,179 days.

Jamie Sorrentini Lugli has not seen her father Irving in 2,953 days.

Quailynn McDaniel has not seen her brother Sean in 2,299 days.

Dylan Gill has not seen his father Russell in 10,865 days.

Mirriam Francis has not seen her brother Ben in 2,533 days.

Claudio and Renata Lugli have not seen their son Flavio in 2,793 days.

Sara Goldberg has not seen her daughter Ashley in 1,833 days.

Lori Hodgson has not seen her son Jeremy and daughter Jessica in 1,545 days.

Marie Bilheimer has not seen her mother June in 1,071 days.

Joe Reaiche has not seen his daughter Alanna Masterson in 5,160 days

Derek Bloch has not seen his father Darren in 2,300 days.

Cindy Plahuta has not seen her daughter Kara in 2,620 days.

Claire Headley has not seen her mother Gen in 2,595 days.

Ramana Dienes-Browning has not seen her mother Jancis in 951 days.

Mike Rinder has not seen his son Benjamin and daughter Taryn in 5,253 days.

Brian Sheen has not seen his daughter Spring in 1,359 days.

Skip Young has not seen his daughters Megan and Alexis in 1,762 days.

Mary Kahn has not seen her son Sammy in 1,634 days.

Lois Reisdorf has not seen her son Craig in 1,216 days.

Phil and Willie Jones have not seen their son Mike and daughter Emily in 1,721 days.

Mary Jane Sterne has not seen her daughter Samantha in 1,965 days.

Kate Bornstein has not seen her daughter Jessica in 13,074 days.

——————–

Posted by Tony Ortega on August 4, 2018 at 07:00

Posted by Tony Ortega on August 4, 2018 at 07:00

E-mail tips and story ideas to tonyo94 AT gmail DOT com or follow us on Twitter. We post behind-the-scenes updates at our Facebook author page. After every new story we send out an alert to our e-mail list and our FB page.

Our book, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology tried to destroy Paulette Cooper, is on sale at Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and audiobook versions. We’ve posted photographs of Paulette and scenes from her life at a separate location. Reader Sookie put together a complete index. More information can also be found at the book’s dedicated page.

The Best of the Underground Bunker, 1995-2017 Just starting out here? We’ve picked out the most important stories we’ve covered here at the Undergound Bunker (2012-2017), The Village Voice (2008-2012), New Times Los Angeles (1999-2002) and the Phoenix New Times (1995-1999)

Learn about Scientology with our numerous series with experts…

BLOGGING DIANETICS: We read Scientology’s founding text cover to cover with the help of L.A. attorney and former church member Vance Woodward

UP THE BRIDGE: Claire Headley and Bruce Hines train us as Scientologists

GETTING OUR ETHICS IN: Jefferson Hawkins explains Scientology’s system of justice

SCIENTOLOGY MYTHBUSTING: Historian Jon Atack discusses key Scientology concepts

Other links: Shelly Miscavige, ten years gone | The Lisa McPherson story told in real time | The Cathriona White stories | The Leah Remini ‘Knowledge Reports’ | Hear audio of a Scientology excommunication | Scientology’s little day care of horrors | Whatever happened to Steve Fishman? | Felony charges for Scientology’s drug rehab scam | Why Scientology digs bomb-proof vaults in the desert | PZ Myers reads L. Ron Hubbard’s “A History of Man” | Scientology’s Master Spies | The mystery of the richest Scientologist and his wayward sons | Scientology’s shocking mistreatment of the mentally ill | The Underground Bunker’s Official Theme Song | The Underground Bunker FAQ

Our non-Scientology stories: Robert Burnham Jr., the man who inscribed the universe | Notorious alt-right inspiration Kevin MacDonald and his theories about Jewish DNA | The selling of the “Phoenix Lights” | Astronomer Harlow Shapley‘s FBI file | Sex, spies, and local TV news