7.

In 2008, all hell broke loose for Scientology. A videotape of Tom Cruise talking about his religion surfaced on the Internet in January, and when the church tried to suppress it, the Internet struck back — in the form of mask-wearing protesters who called themselves Anonymous. Later in the year, after there had earlier been reports of his death, Marty Rathbun started to reemerge from his long hibernation.

“We started to see a lot of Internet chatter about a coalition forming to oppose Miscavige,” Marrick says. “We thought Marty, [former church spokesman] Mike Rinder, and Pat Broeker might be joining up. We told OSA that Marty and Mike were going to be teaming up at least. Oh no, they said.”

Then, in 2009, Rathbun started his blog, and Rathbun and several other executives appeared in a major series by the St. Petersburg Times (now the Tampa Bay Times), and Rinder also began, gradually, to speak out and did, indeed, join forces with Rathbun, just as Marrick and Arnold had warned.

The two investigators were told to keep an eye on all three of them — Rathbun, Rinder, and, as always, Broeker.

In 2009 they traveled to south Texas to do a comprehensive study of Rathbun’s neighborhood in Ingleside on the Bay, which is near Corpus Christi. They scanned the area for the best way to surveil Rathbun around the clock. Marrick says it would take special precautions.

“It’s Marty. You’re not going to just park a car in front of his house,” he says.

After submitting their plan, they were told to move on to other things. Watching Rathbun would fall to someone else.

In the 2009 St. Petersburg Times series, Rathbun revealed the existence of The Broeker Operation for the first time. He didn’t, however, name Marrick and Arnold as the investigators carrying it out.

If their cover hadn’t been entirely blown, Marrick and Arnold say the church did start to treat them differently after that story appeared.

“Things started to get scaled back,” Arnold says. And Hamel told them that if the church needed to make a statement about it, Miscavige would blame Rathbun for creating the operation.

“What about the last 15 years?” Marrick says he responded to her, pointing out that Rathbun hadn’t run the operation since 1993.

“Then the money started getting erratic,” Marrick adds. “Our perception was that Miscavige wanted it all to go away.”

Then, in 2011, things got really strange. In April of that year, several men carrying cameras in their hands or strapped to their foreheads showed up at Rathbun’s house, demanding to talk to him about the counseling he was giving “independent Scientologists” — former church members who have rejected Miscavige’s leadership but still adhere to the ideas of Hubbard.

Calling themselves “Squirrel Busters,” the group planted itself in Rathbun’s cul-de-sac and followed him around town for the next five months. (In Scientology a “squirrel” is a heretic who uses Hubbard’s “technology” in unauthorized ways, and is about the worst thing you can call a Scientologist.)

Marrick and Arnold say their surveillance plan had been used by the church to create a three-ring circus. “It was Three Stooges on LSD,” Arnold says.

“It doesn’t take a lot of finesse to just harass someone,” Marrick adds.

The intimidation squad told local residents that it was a documentary crew making a film about Rathbun, but a local reporter and Rathbun together discovered the truth — hiding at a local hotel was a man named Dave Lubow running the operation. If Marrick and Arnold were Scientology’s silent, secret watchers, Lubow was the private eye the church used for “noisy investigations” and intimidation campaigns.

The camera-toting goon squad managed to get Rathbun arrested at one point. And Marrick and Arnold say that when that happened, Linda Hamel admitted to them that the Squirrel Busters was a church operation. “We just wanted to see Marty implode,” they say she told them.

The Squirrel Busters faded away in November 2011. But Rathbun says he is still being watched. When people come to visit him to learn more about the Scientology independence movement, the church seems to know about it within minutes — some church members have been handed excommunication papers by church operatives within hours of leaving Rathbun’s house.

Meanwhile, the church was falling behind in its payments to Marrick and Arnold. By June, they were owed $100,000, they say. And then they were told no more payments would be coming.

They were out of jobs.

8.

On September 25, Marrick and Arnold drove from San Antonio to Ingleside on the Bay to see Marty Rathbun for their first meeting since 1993.

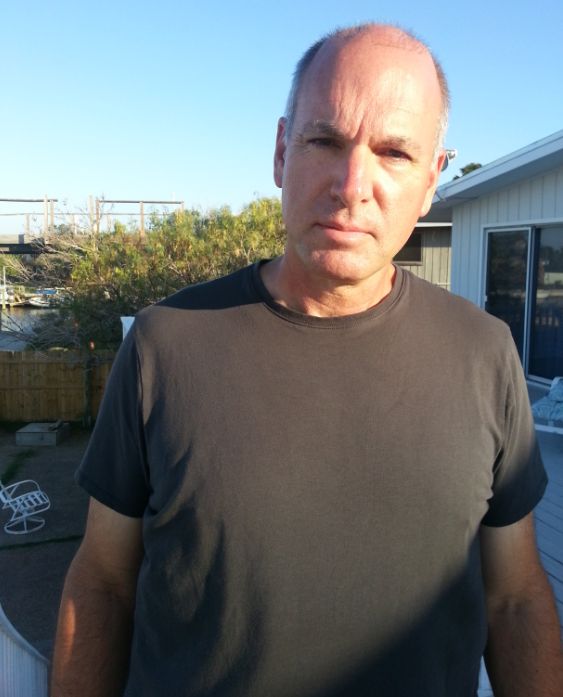

At the reunion, Marrick calls Rathbun “boss,” and the man who hired them in 1988 marvels at what shape Marrick is in.

“Look at you, too,” he says to Arnold. “You look like a young kid.”

Rathbun takes them upstairs, and asks their opinion about a house across the way he can see through his living room window.

For the last year and a half, the house has been empty, but Rathbun suspects that it’s being used as a lookout for Scientology’s private investigators.

Marrick immediately spots something: In an upstairs window, the one with the best view of Rathbun’s place, there are two small cutouts of blinds near the bottom far corner. They would be the perfect size for a camera lens.

“Let’s go for a drive,” Rathbun says, as Marrick and Arnold offer to show him how they had planned to surveil his house in 2009.

The three of them pile into Rathbun’s large pickup along with some members of a British documentary crew and a reporter in the truck’s bed.

Just as soon as they reach the corner and the house they had been looking at, they see a car pulling out of its garage. The driver spots Rathbun’s pickup, appears to panic, and quickly pulls back into the garage and lowers its door.

Not fast enough, though. Rathbun manages to jot down the license plate number.

A quick check on a computer later reveals that the car is registered to a Fidel Garcia Jr., and that his address is also the location of FNG Security Investigations in Corpus Christi.

“We just outed the house,” Rathbun says, sounding satisfied.

“I can’t believe he used his own car,” Arnold says.

“It’s amateur hour,” Marrick adds.

(Later, Rathbun went back to the house, looked into the windows, and spotted remote-controlled cameras that were aimed at his place. He later checked with the home’s owner, and found that it had been leased for the next three years by a Dallas private investigator who Rathbun and Mike Rinder each say the church has used for decades.)

Since he started blogging in 2009, Rathbun has become the most visible member of the growing independent Scientology movement. He insists that he’s not trying to take over Scientology or start a new church. Instead, he provides counseling — “auditing” in Scientology language — to other former members who still admire Hubbard’s ideas but don’t want to be a part of what they say is a controlling, misguided organization.

Still, it was Rathbun who helped set in motion the 24-year watch of Pat Broeker in 1988.

“I regret the whole thing,” Rathbun says.

And why would Miscavige spend so much money — about $500,000 a year for more than two decades — to spy on one man?

“He’s frozen in the moment when he committed the series of coups that put him in Hubbard’s throne,” Rathbun says.

Is Broeker, at 64, still such a threat to Miscavige’s leadership?

“Broeker couldn’t challenge him for leadership now. There’s no legal or PR way that could happen. Pat Broeker is not going to be handed a crown,” Rathbun says. But he does believe that current church members are talking to each other about making changes, and that Miscavige could be toppled.

“Pat could help that happen.”

And what about the significance of Marrick and Arnold coming forward after so many years in the dark?

“It’s right up there with the Tom Cruise summer meltdown,” he says.

Greg Arnold is now 53, he’s married, and he has a son and daughter. Paul Marrick turns 53 in November, and he’s also married with a son and daughter. The two men are too young to retire, but looking for new jobs seems almost impossible.

“Can you imagine our resumes? They’re going to call and verify employment? They’re going to want to talk to Miscavige?” Marrick says with a laugh.

Over the years, the two men read much about the church on the Internet and grew more cynical about their jobs.

“We started to question every operation we were ever on,” Arnold says.

“Everything we were told was lies,” Marrick adds.

But they feel that many current church members are in the same position.

“Scientologists, we feel, are decent people. Some of the things they’ve been forced to do — like disconnection — are things put upon them,” Arnold says, referring to Scientology’s policy that forces members to cut off all ties with those who have been excommunicated, even if it means disconnecting from a family member.

Marrick and Arnold learned about disconnection and many other subjects as they read avidly about Scientology in recent years. Then, when they lost their jobs, they put together their own account of their lives spying for the church in a thick manuscript, and were hoping to give it to a professional to prepare for publication. They knew, however, that their book would never see the light of day if a settlement with the church was reached.

Finally, as they prepared to leave Rathbun’s home, they were asked how they felt about the man they followed for so long. After their jobs were ended in June, were they tempted to reach out to Pat Broeker, to reveal themselves after all this time?

Arnold says they did discuss it, but they decided not to contact him.

And they figure Miscavige must still have someone watching his old rival, even today.

“David obviously cares about what Pat might say,” Marrick says. “It’s obviously important to him.”

After their brief reunion with Rathbun, Marrick and Arnold and their attorneys returned that night to San Antonio.

The next afternoon, after the two private eyes met with reporters from the Tampa Bay Times, their attorney Ray Jeffrey called, saying that he had heard from church lawyers, who were suddenly interested in negotiating a settlement to the lawsuit. Jeffrey said he was instructing Marrick and Arnold not to give any further interviews.

For just a little more than a day, the two spies had talked about their lives undercover. And now, they were going back into silence.

Two months later, we checked with Ray Jeffrey’s office to learn that he was on a week long vacation, and that the case had been “resolved.”

We sent a text to Arnold, asking about the settlement. He sent back a smiley face, and the words, “no comment.”