If it seems incredible that Scientology would so openly surveil the people covering a lawsuit about its surveilling of a perceived enemy, it’s important to remember that now, in its latest filing, Scientology is claiming that surveillance is practically a sacrament of its religious freedom.

Take private investigator David Lubow, for example. He’s been the chief guy for Scientology in recent years to head up its “noisy” investigations. If the church perceives that you’re an enemy worth worrying about, chances are Lubow will suddenly be calling up everyone you ever worked with, or showing up to interview members of your family. The tactic is meant to be as much psychological warfare as it is a method for gathering information.

As for keeping an arm’s length from him so that the church has some deniability about his actions, here’s how former top legal affairs officer and former church spokesman Mike Rinder described how he directed Lubow’s actions while the church claimed that he only worked through church attorney Elliot Abelson.

A freelance videographer named Bert Leahy worked for the Squirrel Busters for a few days, but got disgusted with the work and quit. Later he apologized to Rathbun, and said that a man named “David Statter” was running the operation. Rathbun realized that Leahy was describing Lubow, and Leahy confirmed after looking at a photo of Lubow that it was, indeed, the man who called himself “Statter.”

Statter, Leahy said, had told the Squirrel Busters that their real job was to make Marty’s life “a living hell” by following him around with cameras, never giving him a moment’s rest.

Now, in a declaration, Lubow admits that yes, he did organize and pay for the Squirrel Busters caper on orders from the Church of Scientology International. But he did it, he claims, out of religious outrage.

In 2009 through early 2011, Rathbun made many virulent and malicious attacks against the Scientology religion — of which I am a member. These included appearances in the electronic media through live interviews, interviews to print reporters and his own blog entries. Among public assertions by Rathbun, were … claims that he could provide services to Scientologists in a fashion different from the services the churches offered but supposedly more true to the religion — assertions that are very offensive to me as a Scientologist, to CSI and to any Scientologist. And, as noted above, Rathbun was engaged in delivering Scientology services and counseling at his office/home, for compensation, even though he had been expelled from the religion and possessed no religious authority to provide Scientology services to anyone. These actions of altering standard Scientology practice, and the delivery of altered Scientology counseling, is known in the religion as “squirreling.” In Scientology vernacular, Mark Rathbun was a “squirrel.”

So what did Lubow do, as an offended Scientologist? Well, he did what he’s already well known for doing.

In 2010 I interviewed some former co-workers of Monique Rathbun. The purpose of the interviews was to acquire information regarding Marty Rathbun, his finances, his activities, his associations and his mental state. I interviewed Monique’s ex-husband for all the same reasons.

But then, in 2011, came a special opportunity for Lubow to express his religious outrage.

That March, Lubow says that he had “learned that CSI was willing to provide assistance and some funding for Scientologists who wished to demonstrate against what were perceived as heinous acts by Rathbun.” So he met with Scientologists John Allender and Mark Warlick, and they hatched the idea of the “Squirrel Busters,” which would be part religious protest, and part documentary production.

Lubow explains in his sworn declaration that he was especially qualified for the assignment because he had previously produced an award-winning 2005 documentary titled Prescription: Suicide?

In fact, he writes in his declaration, you can look him up on IMDB, which he says lists him under his filmmaking nom de guerre, “David Statter” as “executive producer” of the film, which debuted at the Ft. Lauderdale International Film Festival that November.

IMDB does indeed list a “David Statter” as a writer and executive producer of Prescription: Suicide? However, IMDB’s page for the documentary itself lists no credits of any kind, but it does have a link to the film’s official website. When you go there, a list of the filmmakers includes Robert Manciero (producer, director, writer), Rich Samuels (producer, writer, editor), David Garland (production), Jace Veck (composer, arranger), Kara Vander Pyl (singer/songwriter), and Marc Haley (singer).

“David Statter” is not listed among the filmmakers.

The film’s website does confirm that it debuted at the 2005 Ft. Lauderdale International Film Festival and contains photographs and a press release from that occasion. But again, there’s no mention of a “David Statter.”

We’ve sent a message to the film’s director, Robert Manciero, to see if he will tell us what “Statter’s” involvement in the film was, and why he wasn’t listed on the film’s website.

Besides claiming to have operated the Squirrel Busters squad because of his background as a filmmaker, Lubow also takes aim at Bert Leahy, the freelancer who got fed up with the project and later helped Marty Rathbun discover Lubow’s involvement.

“Mr. Leahy turned out to be extremely unreliable and incompetent and I informed him after three days that his services were no longer needed, and paid him for his time,” Lubow writes, and he goes on to claim that Leahy lied when he said Lubow had told the team to “make Marty’s life a living hell,” and that Leahy had later tried to extort $20,000 in return for changing his story.

Like the others who took part in the Squirrel Busters crew and provided declarations — John Allender, and Richard Hirst — Lubow asserts that the Squirrel Busters, while showing up day after day on the Rathbuns’ cul-de-sac from April to September of 2011, never pointed cameras in Marty’s windows, never tapped his phones or his Internet service, and never listened inside his house with microphones. (CSI also denies that it had anything to do with the sex toy Monique received from an anonymous sender at her workplace, and it denied forging an amorous note to one of her co-workers with an order of flowers.)

But even if it claims that it never did anything illegal and never actually harassed the Rathbuns, the church’s sheer obsession with Marty Rathbun comes through loud and clear in the many exhibits attached to the motion. CSI’s legal director, Allan Cartwright, turns out to be an obsessive about everything ever uttered at Rathbun’s blog. He also attaches pages which make it clear that Monique Rathbun’s Facebook page is being watched perpetually. (Some of Monique’s friends may be a bit embarrassed to see their lighthearted comments now attached to a court document which is going to be pored over by this lawsuit’s many observers.)

Marty Rathbun probably does not need court exhibits to tell him that every move he makes online is watched carefully by the church. What was more surprising, especially for his wife Monique, was to find a remote-controlled camera aimed at their current property after they thought they had escaped the close surveillance of Ingleside on the Bay.

Steven Gregory Sloat, in his declaration, now admits that he was hired — by a private investigator named J.R. Skaggs — to get information about who was visiting the Rathbuns, “get pictures if possible of persons associating with him, and to meet Rathbun and to get to know him and, if possible, so he would tell me more about what his activities were at that location.”

To that end, Sloat mounted three cameras so they would look through trees to Rathbun’s driveway. The point was to record who was coming and going at the house.

But Sloat claims that the cameras were practically useless, apparently to temper the notion that he might have captured images of the Rathbuns during private moments.

These were cameras typically used in deer runs, had a focal length of about 1-20 yards and could not be adjusted. There was no zoom capability. Objects much beyond the focal length gradually became obscure. The cameras are the type typically used to photograph game, operating on a motion detector and taking a picture when something moved in front of the camera, and had the capability of sending the pictures via cell phone to a web site where the pictures could be seen.

Sloat complains that the “resolution was poor” in the camera images. While he was looking for places to mount his cameras, he found a deer stand he thought was on his land (the Rathbuns say it isn’t), and he wanted to know who had put the stand there. So Sloat mounted a camera and left a note, asking the stand’s owner to call him. But it was Rathbun who found the note and called him. Sloat admits that he spun a tale about using the property for writing a book.

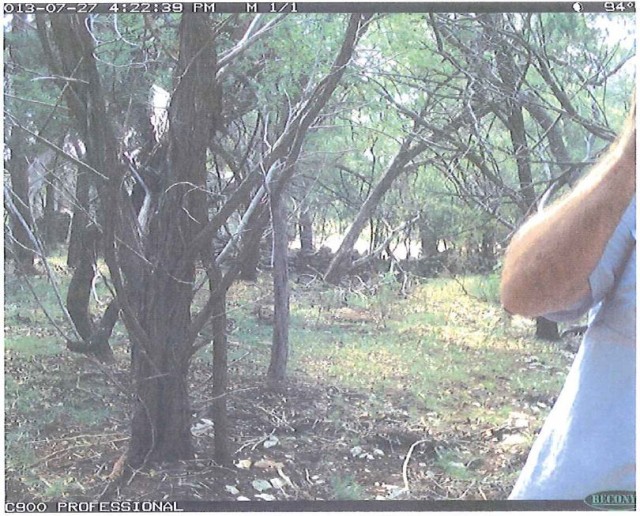

Rathbun later set off the motion detector on a camera when he put tape over it. That image Sloat attached to the exhibit, and we’ve posted it here…

As you can see, the image is actually rather sharp. And from the notations on the bottom border (“C900 PROFESSIONAL … RECONY”), we were able to determine that the camera was a Reconyx PC900 HyperFire Professional High Output Covert IR camera, which has the following specs…

— 3.1 megapixels, 1080P HD

— Color by day, monochrome infrared at night

— Up to 2 frames per second

— Memory card up to 32 GB (about 80,000 images)

— Battery life up to 40,000 images

So, despite Sloat’s sworn testimony, these three cameras could have, if set up properly, sent thousands of HD images of the Rathbun property to a remote website for viewing in Los Angeles or Clearwater, Florida, day or night.

We have to repeat again, these are stunning admissions for a church that has spent literally decades denying every accusation of abuse or retaliation thrown against it.

But will the Church of Scientology International falling on its sword with these admissions provide a way for it to upend this lawsuit?

[Next page: The Montalvo accusations]