Much of our coverage of Scientology in the past three years has focused on former church executive Marty Rathbun, and for good reason.

Much of our coverage of Scientology in the past three years has focused on former church executive Marty Rathbun, and for good reason.

Rathbun is the most visible member of an “independence movement” that is splitting Scientology apart. He has participated in or masterminded several of the biggest legal and media offensives against church leader David Miscavige. And he has also been the target of some of the strangest and most outrageous retaliation in the history of Scientology’s well-earned reputation for vengeance.

But, as we’ve pointed out many times, there is an essential contradiction in Rathbun’s current role as the Church of Scientology’s biggest critic: Before he was the target of the church’s legendary retaliation machine, he was the man at its helm.

Perhaps no other piece has taken on that paradox like Joel Sappell’s masterful new story — his first on Scientology in some twenty years — which appears this morning in Los Angeles magazine.

We were given a sneak peek at the article, which went live this morning at the magazine’s website.

In “The Tip of the Spear,” Sappell tells the story behind the story, describing what he and his partner Robert Welkos went through as they spent five years investigating Scientology, culminating in a legendary 24-part 1990 series in the Los Angeles Times. For most people reading at the time, the Sappell and Welkos series was the first time they learned of Scientology’s secret upper-level teachings about “Xenu” the galactic overlord, or that the church was now being led by a young high school dropout named David Miscavige.

In response, Scientology pulled statements from the series that, out of context, sounded positive, and plastered them on billboards around L.A. It was a typically over-the-top (and expensive) reaction from the church.

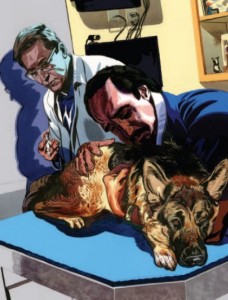

In the years since, Sappell and Welkos have talked about some of the strange harassment they experienced during their investigation. Sappell found himself being questioned for a nonexistent assault by the police. Welkos was pulled over by the California Highway Patrol after an anonymous caller accused him of driving erratically. Welkos also found pamphlets at his home from a nearby funeral home with messages that he should plan for his funeral. Both men discovered that illegal inquiries into their credit histories had been made. But most famous of all, Sappell’s dog, a German Shepherd named Crystal, suddenly exhibited signs that she’d been poisoned before he had to put her down. (Sappell reveals that he received a call from Judge Ronald Swearinger, who had heard about Sappell’s dog and suspected that someone from the Church of Scientology had drowned his collie. Swearinger presided over one of the most famous lawsuits against the church, brought by former member Lawrence Wollersheim.)

Was it all being done by the shadowy forces of Scientology’s covert operations team, the Office of Special Affairs and its private detectives?

A few months ago, Sappell realized that he finally had a chance to answer that question now that Marty Rathbun, once the church’s top enforcer, was out of the church and had become its biggest enemy.

So in October, Sappell traveled to Rathbun’s home in Ingleside by the Bay, a small town near Corpus Christi in South Texas. (Rathbun and his wife Monique tired of the constant church surveillance they were under in their Ingleside home and recently moved to a more secluded house near San Antonio.)

Sappell captures perfectly what it’s like to meet and talk with Rathbun, and how different he seems today compared to the menacing church executive he was in the 1980s…

He looks like a regular guy — cargo shorts, sandals, a well-worn plaid shirt covering a middle-age paunch. The last time I saw Rathbun he was in his twenties. His athletic six-foot frame was clad in the strange spit-and-polish mock Navy uniform of Scientology staffers, members of the so-called Sea Organization, or Sea Org — and he was glaring at me. Today he reminds me of a high school gym teacher. His blue eyes have a friendly crinkle at the corners as he smiles at me for the first time, ever.

But if Rathbun has aged and mellowed, he’s not as forthcoming as Sappell was hoping.

Sure, Rathbun tells Sappell that he was followed by church spies…

This “patina of terror,” Rathbun tells me, was Scientology’s desired impact. “You were everywhere,” he recalls as we drink water out of jam jars. “And it was really pissing off Miscavige… ‘Fucking weasel Sappell. Fat fuck Welkos.’ This is the way the guy talked.” The message, Rathbun says, was clear: “Crush them.”

But if Rathbun confirms for Sappell what he’s wondered all these years — yes, there was an active and large-scale harassment campaign intended to unsettle the two reporters — the former enforcer proves maddeningly vague when Sappell tries to pin him down on specifics.

When I ask about the private investigators who dogged us, he quickly asserts, “I never hired an investigator to investigate you.” A moment later, however, he concedes that what he means to say is that he never personally hired an investigator. He says the “intel” guys under him took care of that job for him. “It goes through that machine, and I’m just getting reports,” he says so matter-of-factly that we could have been talking about the weather or holiday plans.

At times during their conversation, Rathbun admits to things like getting copies of Sappell’s phone records — but only second- or third-hand, through the actions of operatives he had no involvement with. At other times, he says he would never have approved operations like the CHP stop of Welkos, but that it could have been done by underlings he had no control over. Rathbun seems to alternate between taking the blame for years of heinous activity, and wanting to be seen as blameless for it.

“Sometimes he seems to be having a dialogue between the new Marty and the old,” Sappell writes.

There was no question, Rathbun told him, that Miscavige had a special hatred for Sappell and Welkos, and held brainstorming sessions to come up with ways to derail their series.

But Sappell keeps pushing for more specific answers.

Like, did Scientology poison his dog or not?

Rathbun tells him that pets were off limits and there was no way that he would have had anything to do with harming Swearinger’s dog or Sappell’s. But once again, he hedges, saying that it could have been “third parties” that wanted the church to look bad — maybe even agents of the IRS.

Sappell finds that doubtful. And then Rathbun admits that he keeps a close watch on his own dog Chiquita with so much Scientology surveillance going on. “I don’t put it past the sons of bitches, you know what I mean?” Rathbun tells him.

If Sappell didn’t find all of the answers he was looking for when he went to Texas, he writes that he did find it exhilarating — and somewhat terrifying — to get back into a subject he thought he’d left behind years ago.

As he explains, when you investigate Scientology at this level, you aren’t putting only yourself at risk. Before he was sure he would take on this piece, he talked to his family, his old partner Bob Welkos, even his ex-wife, all of whom he knew might come under a new round of “noisy investigations” and harassment.

It was his ex-wife Linda who had helped him care for their dog when it suddenly took ill, and that’s what they talk about when he calls.

I begin to tear up. I tell her I’ve always felt guilty that my job may have brought harm to the dog we both loved. I thank her for taking such good care of Crystal. Tacitly I’m also thanking her for putting up with my obsessive pursuit of a story, for her patience, for talking to me now. Before saying good-bye, I make her promise she’ll call if she gets any uninvited visitors.

We got the feeling, reading the concluding paragraphs, that Sappell is still unsure of his decision, and wonders if some will see his new investigation, all these years later, as a waste of time.

We can only assure Sappell that we are grateful that he decided to return to the fray.

As for Rathbun, this isn’t the first time he has been taken to task for not saying as much as he might about the church’s covert operations under his guidance. (Some of our commenters relentlessly hammer him for not saying more, for example.)

But Rathbun has defended himself in the past by pointing out that he was very forthcoming with the FBI three years ago, and that it wasn’t his fault that the agency dropped its investigation of the church. And when, for the first time, Rathbun was put under oath recently, he spilled his guts about a years-long conspiracy by the church to corrupt Florida’s state courts system.

Is he still holding back more than he should? If so, is he protecting himself or playing some kind of elaborate poker game and holding his chips for when they might be most effective to gamble? Or was he, as he tells Sappell, a high level report-taker who didn’t always know the reprehensible things that were being done in the name of the church?

Whatever the truth, Marty Rathbun is a fascinating character who may have done more in the last three years to cripple the Church of Scientology’s seemingly indestructible vengeance apparatus than the press and other critics have managed in decades.

And for that, he is worth the kind of attention that he’s getting from journalists in the UK and Australia. And perhaps Joel Sappell will begin to make a larger American audience realize that something very odd and intriguing is happening down in Texas.