When you’re the target of a Scientology “noisy” investigation, the thing that’s the most unsettling is the not knowing.

Whether you’re a former member of the Church of Scientology, or you’re someone who investigates and writes about the organization, or you’re just a curious citizen who wants to disseminate information about Scientology’s controversial practices, you may find that your family members, your co-workers, even people you went to school with you haven’t talked to in many years are suddenly hearing from private investigators asking for information about you.

And the many people we’ve talked to who went through it tell us that what nags at you — and what Scientology counts on, say its former spies — is for you to be left wondering, who are these people looking into every aspect of my life?

Very rarely do we get a full picture from both sides about Scientology’s many legendary retaliation operations. In our 2015 book, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely, we had some success not only finding new details about the harassment campaign experienced by journalist Paulette Cooper, but we also talked to numerous people who had actually taken part in those operations.

Now, we have another opportunity to see and understand Scientology’s “Fair Game” with new clarity. And that’s because the man who investigated and harassed and tried to intimidate a Canadian man named Gregg Hagglund on behalf of the Church of Scientology has given up his secrets about those operations.

And that’s because he died.

His name is Peter Ramsay, and for many years he was a volunteer for Scientology’s Office of Special Affairs who took very seriously his role as a spy and dirty tricks operative, which is spelled out in detail in his personal papers. Ramsay died on April 26, 2013, and we’ve mentioned him a couple of times here at the Bunker. His son, Jonathan, who was never a Scientologist, has tried to get the church to return money to him that his father had on account and will never use. Helping him with that is Peter’s brother, Rob, who reached out to us with questions about Scientology.

Then, in December, Rob Ramsay did a remarkable thing. He sent a message to Scientology attorney Gary Soter, offering to return to the church all of his brother Peter’s personal papers, including sensitive documents that showed years of Peter Ramsay’s spying on Gregg Hagglund.

Soter didn’t respond.

So, instead, Rob turned over those documents to us. And now, after interviewing Hagglund and Rob Ramsay and others, and going through Peter Ramsay’s personal papers, we’ve been able to piece together this examination of a Scientology Fair Game operation from both sides.

When William Gregory Hagglund was born in Edmonton on May 5, 1951, the news was related to his father Melvin Hagglund in an interesting way.

Melvin was a soldier stationed at Resolute Bay, an outpost famous for being among the most northerly and isolated settlements in Canada. Gregg’s mother, Wilma, could only get word to her husband by ham radio, to let him know that their third child had come a little early.

Pleased to hear that he had a second son, Melvin wanted to hear from the infant himself.

“Pinch him,” he said to Wilma over the radio. And Gregg obliged with a yelp.

With his father in civil service after the military, Gregg moved around a lot as he grew up. By grade 10, he had attended 13 different schools. And after school, at 19 he ended up in Resolute Bay himself working for the civil service, and found that his father was well remembered there — he got to ride a snowmobile that had his father’s name on it.

Between his work in the civil service and some gold mining he did on the side, at a young age Hagglund found himself weighed down by money. He decided to go to college, where he met Jennifer Plesch.

They married in 1975 and moved to Toronto, where Gregg got a job at a unique game store, “Mr. Gameways’ Ark.” It was part of a small chain of game and hobby stores that were growing in popularity, and Gregg invested most of his fortune in it.

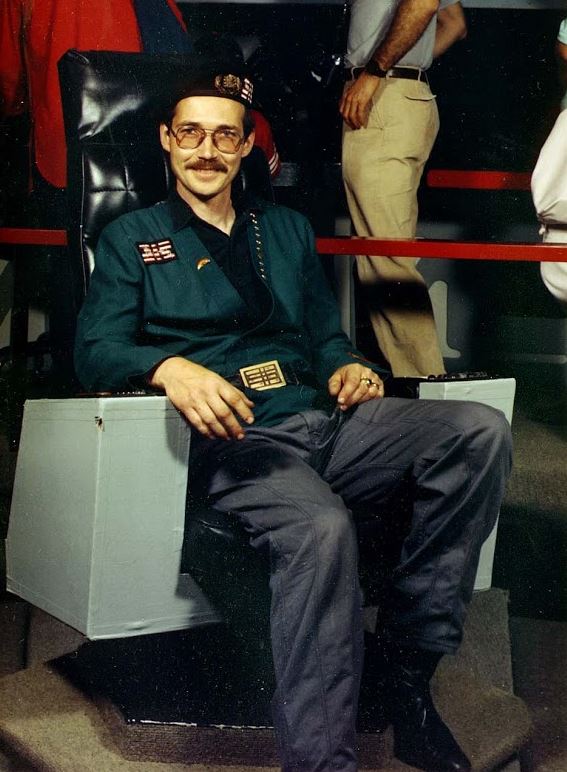

His timing seemed to be perfect. Gameways’ Ark was booming in part because it had a special deal with the makers of Trivial Pursuit, which was becoming a phenomenon. And Gregg found that the store was a great outlet for his geekish creativity. He built at the store a full-scale replica of the bridge of the Starship Enterprise, and it became a local hit, especially with Star Trek: The Motion Picture coming out in 1979. (Also arriving that year was Gregg and Jennifer’s son, whom they named Christopher.)

And then, just three years later, the store came crashing down like a decloaked Romulan Warbird. Hagglund was wiped out in the store’s demise.

He had lost $1.2 million, and he was only 30 years old.

Hagglund then made forays into the early online world, and tried to make a go in CGI, but eventually he settled into a job in the cable industry. Jennifer, meanwhile, was teaching as they worked steadily and paid off debts.

Then, in the early 1990s, the Hagglunds dealt with more difficulties. Jennifer turned out to have a tumor on her brain that, although benign, needed to be removed. And the only way to do that was for surgeons to temporarily remove her face.

She came through it, but both of the Hagglunds were deeply affected by it. And one way they coped was through their adventures in spirituality.

The Hagglunds had experienced what Scientologists might call a cognition. In fact, what they discovered for themselves has a parallel in one of Scientology’s most central concepts.

Gregg Hagglund believed that he’d lived before.

“I have absolutely no scientific proof that what I believe is true,” Hagglund says as he explains that unlike Scientology, he calls his ideas faith, not science.

“I’m never going to say that I have scientific proof of what I believe,” he adds. “I believe that I have access to continuing living memory of people who lived in the time of Atlantis, going back 15,000 years. We believe that’s the basis for reincarnation.”

In the mid-1990s, the Hagglunds formed what they call the Temple of At’L’An to promote their beliefs, and Gregg began thinking about writing a book.

Familiar with how the online world was developing, Gregg wanted to see what was being said about religion in that world, hoping to get some ideas for how to aim his book in the best possible way.

That drew him to the Usenet, with its many discussion groups, including vigorous debate about religion. And that’s how he ended up one day in 1996 at the Usenet group alt.religion.scientology.

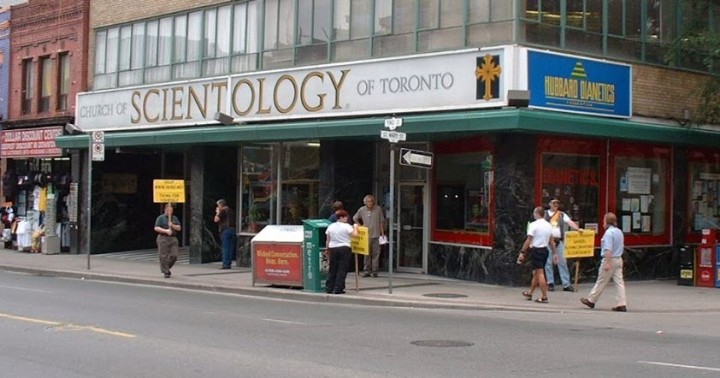

ARS had been created in 1991 but had caught fire a few years later and by 1996 was the busiest place to find news about what was happening in Scientology, including the church’s attempts to suppress discussion about it online. In 1995, a Scientology attorney had even tried to have ARS removed from the Usenet, which only made it more popular than ever. Meanwhile, former church members had used ARS postings to put secret Scientology teachings online, and Scientology had used a legal scorched-earth approach to get those teachings taken offline, even going so far as to convince law enforcement agencies to raid the homes of some of the people who had been making the postings.

In other words, Hagglund had no idea what he was walking into.

“It took me hours to look through various threads. It was fascinating. I began to realize that there was a real contest between people who criticized Scientology and the trolls and the people opposing them,” he says.

“I made a comment or two about it. Within moments, I got responses saying I needed to educate myself,” he says with a laugh, remembering his time as a typical “newbie.”

“It looked difficult to me. So I said thank you, not interested.”

Hagglund could see that ARS was a tough playground, and he wasn’t really interested enough to do the background work to hold his own there. He probably would have walked away and forgot about ARS.

But the next day, when he dialed in to his Internet provider, he was in for a shock.

“I got email bombed,” he says. “I was downloading emails for hours. I had thousands of messages. I had to call the Internet provider. They stemmed the tide at their end, then they cancelled my email account and I had to start over.”

Over and over, he was receiving a message that told him that he had no right to comment on Scientology, and it suggested that he go back to ARS and apologize for saying anything at all. It also told him to keep away from xenu.net, a website that had been started that year by an engineer in Norway, Andreas Heldal-Lund, who was amassing a huge collection of damaging information about Scientology.

“That really pissed me off,” Hagglund remembers about the email attack. “Until that moment, I didn’t give a screw about them. But I thought, what a bunch of arrogant shits.”

Gregg reacted to being told he should stay away from xenu.net by reading everything he could find at the site.

“I realized that Scientology was a group of proto-Nazis who wanted to control the world,” he says. “Lives and livelihoods were being destroyed. Scientology was destroying a lot more than it was creating.”

Gregg steeped himself in Scientology jargon, trying to become proficient in it. And after he’d done that, and with advice from his son about how to protect his computer, he was ready to dive back into ARS.

“I got another email bomb, but this time it was bounced off,” he says.

And that’s how Gregg Hagglund, believer in past lives and avatar of Atlantis, went to war with Scientology on the Internet.

As Gregg Hagglund’s transformation into a critic of Scientology began, Scientology itself was plunging into a crisis.

On December 5, 1995, a 36-year-old Scientologist from Dallas named Lisa McPherson died after being confined for 17 days at Scientology’s holiest place on earth, the Fort Harrison Hotel in Clearwater, Florida. (See our series about Lisa’s final days.)

A year later, news of the death finally reached the press, and then began to turn into the worst Scientology media nightmare in years. The church itself was indicted on two criminal charges and the family of McPherson filed suit against Scientology.

As the McPherson matter blew up, pickets were being held outside the Fort Harrison Hotel in Clearwater. At the same time, through the Internet Gregg had gotten to know an ex-Scientologist in England, Roland Rashleigh-Berry, who had been roughed up during a picket there. Those incidents led Hagglund to decide it was time to take his fight against Scientology beyond his computer screen.

“I decided I would picket too,” he says. “But I didn’t want to do it alone. I posted on ARS that if anyone wanted to join me, I would be picketing the Toronto org on a particular day.”

On May 10, 1997, Hagglund made the first of what became monthly pickets that stretched over the next five years.

“I ended up with a core group of three guys and myself. And Scientology had 30 people out there to quell us,” he says.

Today, in the wake of the 2008 Anonymous protests, Scientologists usually scatter when picketers show up. But in the 1990s, they were much more aggressive, as can be seen in videos taken during that time by people like Mark Bunker.

In Toronto, Hagglund says they were yelled at by Scientologists at the org, and the church members tried to convince police to arrest them.

“This was back in the day when Scientology reacted in a very in-your-face style,” says Ron Sharp, who learned about Hagglund’s pickets through ARS and joined him soon after they began. (At the Underground Bunker, Ron goes by “RMycroft.”)

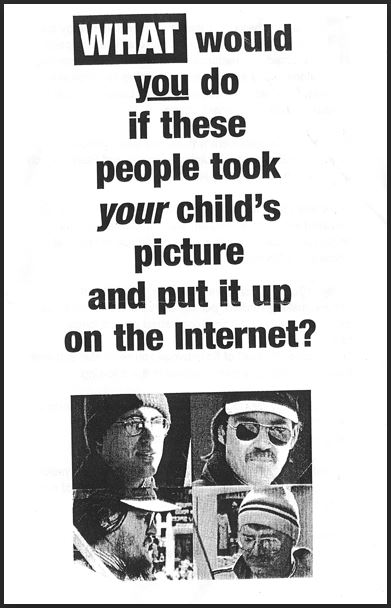

“It was street theater. We’d walk up and down with signs. We’d hand stuff out. Then they started handing things out. Fliers with our pictures on it that said ‘These people are not what they seem.’ They were accusing us of taking pictures of their children and posting them on the Internet. But kids were in the photos because they were using children to promote Scientology in their events,” Sharp adds. (Hagglund says the website that contained photos of children didn’t last long. He took it down in 1998 because he couldn’t maintain it.)

Scientologists weren’t the only ones taking notice of the pickets. Hagglund says local business owners couldn’t help being interested. And after the third monthly demonstration, Hagglund found himself invited by a salon owner to a local business owners’ meeting to give a presentation about himself and the Temple of At’L’An.

Hagglund says he knew that Scientology’s local spokesman, Al Buttnor, was a regular at the meetings, and he knew Buttnor would be surprised to learn that he’d been invited. Hagglund decided to play it up as much as he could.

“I showed up in my temple collar. Buttnor just about shat bricks. Everybody at that meeting were just killing themselves,” he says, remembering how much the other business owners were enjoying it.

“After the meeting, Buttnor followed me out and said he wanted to talk to me. I stopped at a street corner under the full light for safety. He asked, What the fuck do you think you’re doing?” Hagglund remembers.

Hagglund played his part to the hilt, telling Buttnor that he was going to rent a vacant storefront and he’d use it to put out literature about Scientology. “And we’d have e-meters and we’d show people how they actually worked,” he says with a laugh. “None of this was even possible, but it got him so upset. ‘You can’t do that! That’s religious bigotry!’ he said. And I told him, ‘But you’re not a religion, you don’t have charity status.”

Scientology had not been granted tax-exempt status in Canada as it had been in the United States in 1993. “In Canada you have to have religious charity status to call yourself a religion, I told him. So Buttnor answered, ‘We’re going to have that, we’ve applied for it.’

“Boom!” Hagglund exclaims, remembering what a bombshell that was. “First thing I did when I got home, I looked into it. I knew how Ottawa worked because of my dad.”

With his father’s background in the civil service and his own years in it, Hagglund was familiar with how government worked at the capital. He knew that the government could never say publicly that an application had been made by Scientology for religious charity status, or that it was reviewing one. But now that Buttnor had blurted out that piece of information, Hagglund knew he had an opportunity to do something about it.

Asking around at ARS for advice about how to gather background information on Scientology that he would need, Hagglund was referred to University of Alberta professor Stephen Kent, who is one of the foremost scholars on Scientology and has one of the largest document collections in the world. Kent in turn introduced Hagglund to Nan McLean, who had spent a few years taking courses at the Scientology Toronto org in the late 1960s and then had become one of the best known critics of the organization.

“She connected me with a network of people all around the world who began sending me documents. I mean, these were originals!” Hagglund says. “It was a very exciting time.”

With advice from his father, Hagglund worked to put together a comprehensive document arguing why Scientology’s application should be denied. When he printed it out to submit to Revenue Canada, it filled three separate binders. Hagglund remembers that it took about four months to assemble after that night Al Buttnor had revealed his secret.

Hagglund not only submitted his three-volume brief, he was asked to give a presentation about it and was surprised when 30 people from Revenue Canada came to hear it. Hagglund used Scientology’s own internal documents to show that it was a moneymaking operation, not a religion. He says his audience seemed particularly interested when he showed them a Scientology chart that said the purpose of an org was to produce satisfied customers. “There was nothing about religion anywhere on it,” he says.

Scientology’s application for charity status has never been approved. And Hagglund has been told by government sources that his three-volume brief was a major reason why. And more importantly, Scientology itself was convinced of it, Hagglund says.

Hagglund had graduated from being a vocal critic at ARS. He was now becoming a real problem for Scientology in Canada.

Peter Ramsay was so sharp, and so talented, he skipped two years of public school growing up in Ontario and then, in his teens, picked up the classical guitar in addition to his piano training.

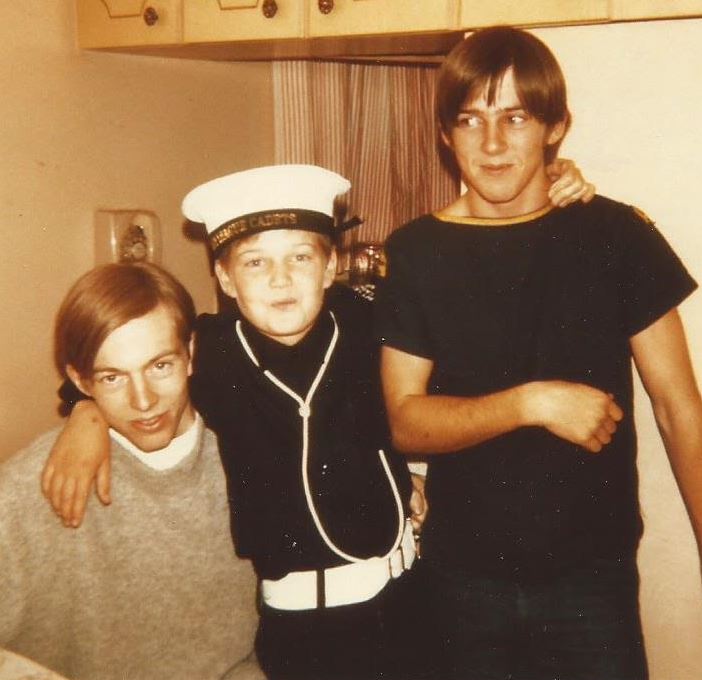

To his younger brothers, Ian and Rob, he was an overachiever they wanted desperately to be like.

Peter had been born on June 19, 1949 at Sarnia General Hospital in the western Ontario town on the southern end of Lake Huron. Ian was born in 1952, Rob in 1956. Their father worked for Ontario Hydro, the electric utility, and mom was a nurse as the family moved to Toronto.

Peter became so proficient at the guitar so quickly, by the time he was about 19 he fell in with a group of top Toronto studio musicians who played with singer Peter Shields in a loose funk group known as Simon Caine.

The group’s drummer, John Savage, was into Scientology, and introduced Peter to it. As Peter’s music dreams faded and he got work in the building trades, his involvement in Scientology grew.

“Peter was having problems with anxiety. Scientology seemed to help him,” Rob Ramsay tells us. And though Rob was very young — only 15 — at Peter’s urging he took some courses in 1971. Peter even encouraged his youngest brother to get a job working on the staff at Scientology’s Toronto org.

“I brought home a form for my dad to sign, but he refused. We got into a big argument about it. Thinking back, I dodged a bullet there,” Rob says with a laugh. He didn’t explore Scientology any further. (Later, he started a long career at CBC Radio.)

Peter’s interest in Scientology only deepened. The church is where Peter met Suzanne Fortin; the couple were married and then had a son.

Later in the 1970s, Peter also had some success interesting his brother Ian in Scientology. Ian paid $1,500 for three “intensives” (12.5-hour blocks) of auditing, Scientology’s version of counseling. In addition, Ian paid $100 for an introductory level called the Hubbard Qualified Scientologist course, planning on taking it later.

After his auditing, Ian felt that it had been a waste of time and decided he didn’t want to have anything more to do with Scientology. But the church was already notorious for hounding people about taking more courses, and Ian was receiving a steady stream of annoying phone calls and letters.

Fed up, he knew that if he demanded a refund on the money he’d paid for the HQS course, he’d be “declared” a “suppressive person” and the church would leave him alone. So that’s what he did, first requesting his money back in a letter to the church, and then filing for his $100 in small claims court.

Wait a minute, we told Ian. You actually sued the Church of Scientology? There’s not a lot worse that a person can do as far as Scientology is concerned, we told him, and the repercussions for Peter must have been immense.

“Peter was visibly and verbally upset with me,” Ian replied. “He could be declared if I continued with this course of action.”

In court, Ian not only demanded his money back, but he also wanted the church to provide a letter saying it wouldn’t punish Peter for what he had done. And in court, he won both. “It was a pretty easy go of things. The church had a money back warranty,” he remembers.

Ian says the judge wrote out the agreement stipulating that the church not retaliate against Peter (as well as some others), and both sides signed it.

“I felt elated,” Ian says. “Not only had I successfully severed all ties with the church — they would never again be phoning, writing, or showing up knocking on my door — but I had managed an agreement wherein Peter and other friends had been protected.”

But things didn’t turn out that way. Peter, he found out later, was punished, and probably repeatedly so for years afterwards.

“He was terrified by this concept of me suing the church. He let me know I wasn’t his brother any longer,” Ian remembers.

Meanwhile, both Ian and Rob came to understand that Peter had not only become very dedicated to Scientology, but fairly early on he began volunteering for its more unsavory operations.

Ian says that he became aware that Peter was volunteering for Scientology’s notorious “Guardian’s Office,” its spy unit that in the 1970s was infiltrating and burglarizing government offices in the US, Canada, and other countries, following the outlines of an operation Scientology’s founder, L. Ron Hubbard, called the “Snow White Program.” (The Guardian’s Office was disbanded by Scientology in 1981 after the Snow White Program resulted in a 1977 FBI raid of the church’s facilities in Washington DC and Los Angeles. Eleven top GO executives were convicted and went to prison as a result. We haven’t found evidence in Peter Ramsay’s papers that he was involved in any Snow White Program operations, or that he had volunteered for the GO, as Ian was told. Peter’s papers are filled with references to the work he did for the GO’s successor, the Office of Special Affairs.)

Rob remembers that his brother was becoming something of an enforcer for the organization.

“What I remember is that there was someone well known in the Toronto church who had quietly left and went to the ‘freezone’,” Rob says, referring to people who practice Scientology’s processes outside of the official church. “Peter went out and set the guy up to reveal what he was doing, and then he turned him in to the church, calling him a ‘squirrel.’ Peter’s friend who got him into the church was mystified by that.”

“He wasn’t a vindictive or mean individual, he was just enforcing church policies,” Ian adds.

“In my mind, Peter needed Scientology to work to handle his anxieties and all of the problems he had. And in his head, someone was trying to take that away from him by criticizing Scientology, so that’s why he went on the attack,” Rob remembers.

“We’re a close-knit family, and prior to joining the church Peter was a pretty straight guy,” Ian says. “He was very generous, and he always helped people.

“But he certainly changed.”

In Peter Ramsay’s papers, there’s a certificate for reaching “Clear,” a major intermediate goal for a Scientologist progressing up the “Bridge to Total Freedom, Scientology’s increasingly expensive rubric of courses and counseling. There’s also a document showing that in 1991 Ramsay was subjected to a “board of investigation” to determine if he would be “ineligible for training or processing.”

Like so many others who had dedicated themselves to Scientology, Peter found that his very progress on the Bridge was being threatened by some perceived deficiency. Scientologists in that position, who get assigned to a lower “condition,” must then work their way back into good standing.

They can do that in a number of ways. For some, that means volunteering to do work for a particular Scientology division. In Peter’s case, as the 1990s continued, that meant volunteering for Scientology’s secretive Office of Special Affairs.

A year later, in 1992, he was given a special commendation by OSA for his work helping the church’s intelligence wing.

Peter Ramsay, Toronto public, is hereby very highly commended for his work for the Office of Special Affairs over the past year. As a bonus, Peter is awarded the Hubbard Key to Life Course. Per HCOPL ‘Staff Member Reports,’ his ethics file is to be cleared without comment. This commendation has been approved by CO OSA Canada and CO All Clear Canada.

That commendation didn’t spell out what Ramsay was doing for OSA. But another one, given to him four years later in 1996, alludes to Peter’s work helping with an important propaganda project the year before.

In 1995, Scientology Canada had reason to be very worried about its image.

Twelve years earlier, in 1983, the Toronto org had been invaded in the biggest police raid in the country’s history. Six years after the FBI raided Scientology over the Snow White Program in the US, Canadian authorities came down on Scientology Canada with similar allegations — that in the late 1970s, church operatives had infiltrated and burglarized Canada’s law enforcement and other government agencies in order to steal and destroy official documents.

A year later charges were filed, and a trial in 1992 resulted in convictions against the church itself and one of its officials.

Scientology — the organization itself — had been found guilty of a felony. And now, in 1995, an appeal was winding its way to the nation’s supreme court, and Scientology wanted to have some influence on it.

According to his OSA commendation, Ramsay helped research a 1995 pamphlet, “A Conspiracy Revealed,” that Scientology’s Freedom magazine put out, providing the church’s slant on the Snow White prosecutions, that the church was being victimized by a cabal of biased law enforcement officials in bed with former church members.

Although Ramsay got his commendation, the pamphlet apparently didn’t have much effect. In 1997, the high court upheld the convictions, as well as a libel judgment against Scientology, which had smeared the prosecutor, Casey Hill, who eventually collected more than $4 million from the church.

“Every aspect of this case demonstrates the very real and persistent malice of Scientology,” the court said as it upheld the verdicts.

It was a thorough thrashing by the country’s highest court. But Scientology never gives in. It always gets even.

And so Peter Ramsay moved on from propaganda to another role for the Office of Special Affairs.

It was time to Fair Game a man named Gregg Hagglund.

[Continued on page two]