Coffeyville, in the southeast corner of Kansas, is best known for a botched double bank robbery in 1892 which cost most of the Dalton Gang their lives.

After the cattle-drive days it had some minor prosperity as a center of light industry until the 1929 crash, but has been slowly shedding businesses and people ever since, and is now ranked as the fastest-shrinking and most economically distressed city in the state.

Last October Lizzie Presser of ProPublica wrote an exposé on how Coffeyville treats those who are faring worst. An attorney for the creditors, usually Michael Hassenplug, summons the debtors before Magistrate Judge David Casement not just once but repeatedly, in what Kansas law called “debtor’s examination” (the law specifies only “from time to time”; every three months has become typical in Coffeyville) to delve into their financial circumstances and determine what is the maximum feasible payment plan or wage garnishment. The magistrate can cites no-shows for contempt, and if they miss the contempt hearing issue a bench warrant: Casement makes some effort to check whether the debtor was actually notified of the court date, but Presser found multiple instances of people who had no idea they’d been summoned at all, until they learned of the warrant.

Most unusually, Casement leaves it up to the creditors’ attorney whether to issue a warrant. “I’m not ordering a bench warrant. My decision is to give them that option,” Casement told Presser. “Whether they exercise it is up to them, but they have my blessing if that’s what they want to do.”

The most relentless creditors are the Coffeyville Regional Medical Center (the only hospital within 40 miles) and its affiliated doctors and ambulance service. Presser went in depth into the case of Tres Biggs, who learned in 2007 that his 5-year-old son Lane had leukemia, while his wife began suffering symptoms of Lyme disease. This made it impossible for him to obtain health insurance for his family under the “pre-existing conditions” rule. When the Affordable Care Act changed this, then-Governor Sam Brownback refused to let Kansas participate in federal subsidies for Medicaid, and insurance premiums have gone up well beyond the reach of the working poor.

Biggs eventually got a job with Blue Cross benefits, but only with a $5,000 yearly deductible. His medical debts, subjected to a 12 percent interest rate, have ballooned to $70,000. Since cases larger than $10,000 are beyond of the magistrate, the litigation is broken into separate cases for each bill to keep the matter in Casement’s court. The Biggs family has been through every stage of these procedures including jail. Lane is better now, but Heather sometimes has seizures, and when she regains consciousness begs, “Please don’t take me to the hospital.” (On its side, the hospital says it has to write off about $1.5 million in uncollectable medical bills every year, forcing it to raise charges on those who do pay, or go out of business.)

The sheriff’s deputies make sure that anyone jailed under a bench warrant is subjected to the full humiliations: stripped, hosed down with delousing solution, and put in jumpsuits. Bail is set at $500 which is not returned, but given to the creditors. Hassenplug takes a one-third contingency fee, and after expressing annoyance that debtors have to miss court twice, once for the debtor’s exam and then for the contempt citation, before a warrant issued, obtained a ruling from Casement that anyone who missed an

examination twice would have to pay $50 “plaintiff attorney fee” before posting bail, and would have to serve at least two days before bailing out. The ACLU questions the constitutionality of not returning bail after its usual purpose (ensuring appearance in court) is served, and of sentencing debtors to prison without a finding that they are able to pay (which few are).

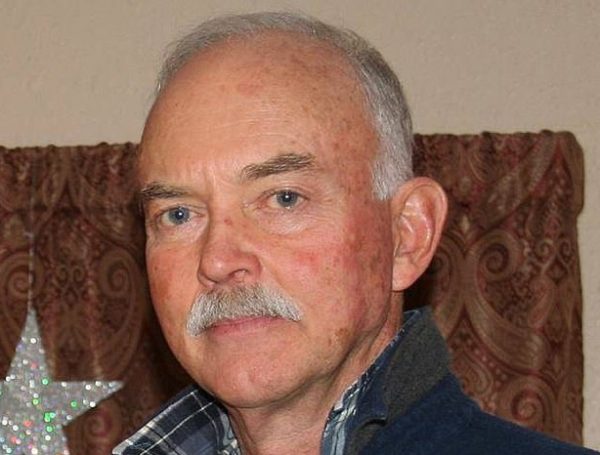

Casement says he has “not seen enough pushback from defendants” to be persuaded he is doing anything unlawful: Casement, a former rancher, has no legal education or license, and was only required under Kansas law (K.S.A. 20-337) to complete a certification test from the state supreme court to get and keep his magistrate’s job, and this test only covers basic procedures and rules of conduct. When the ACLU involvement attracted the attention of the CBS affiliate 13-WIBW, they found 60 defendants at a debtor’s exam day, only one of whom had a lawyer. They were denied cameras in the courtroom, but interviewed the Biggs family for a piece that aired February 10.

Candidate Bernie Sanders used Twitter to call attention to the story.

A lifelong resident of Coffeyville, who prefers to remain unnamed, has a very low opinion of Hassenplug from a contentious run-in with him 20 years ago about a 13-cent discrepancy. This correspondent says that scuttlebutt in town attributes Casement’s increasingly extravagant assertions of power to envy of the other judges, who have been to law school, have the rank to hear more important cases beyond a magistrate’s jurisdiction, and are more highly respected in the community. Among the legal “loopholes” that have let Casement and Hassenplug get away with their behavior, she cites not only the use of “contempt of court / failure to appear” as an excuse to jail people, when everybody knows failure to pay is the real reason, but also a lack of legal protection for those who cannot miss work, without losing their jobs, or miss medical appointments to come to court (the Biggs family missed court at least once because it clashed with Lane’s leukemia treatment in Tulsa).

The debtor’s exam sessions give Hassenplug the opportunity to learn all about work and treatment schedules, so that further court dates can be set for maximal inconvenience. Her husband, who is already under wage garnishment, and her daughter’s fiancé, who was briefly pronounced dead during a seizure episode last summer, have medical bills they will never be able to pay in full, which “absolutely terrifies” her.

Robert Eckert is a longtime member of the Underground Bunker community and author of the historical novel The Year of Five Emperors.