Even tabloid TV didn’t buy Brice Taylor’s claims of being a CIA sex slave. But Channel 13 saw higher ratings in her ravings.

By Tony Ortega

From 1999 to 2002, we worked for New Times Los Angeles, a feisty weekly newspaper that succumbed to economic forces in October 2002. The paper’s archives disappeared along with the publication itself. One of the stories we were sad to see vanish was this piece we put together, painstakingly annotating a local TV station’s attempts to treat seriously a subject that was patently outrageous. Here is that story, which was originally published on December 7, 2000.

For several days running, KCOP-TV Channel 13 had been promoting its blockbuster investigation. Radio spots touting the special report had aired repeatedly, teasing listeners with salacious but vague details. Finally, in the middle of the UPN affiliate’s ten o’clock news program on November 2, which followed an offering of professional wrestling, the big story was ready to roll.

After a commercial break, anchors Rick Chambers and Lauren Sanchez appeared on-screen, materializing out of a graphic signifying that the forthcoming story was a production of a special investigative crew.

Chambers had become KCOP’s male anchor 13 months earlier. Previously, he had been a weekend anchor with KNBC after moving from a Miami station in 1992. Sanchez started at KCOP as an unpaid intern after receiving a communications degree at USC. She managed to secure a paying job as a producer, then moved to Phoenix to get her first on-air experience at an independent station there. Sanchez then became a national correspondent for the magazine program EXTRA, prompting the Albuquerque Journal to predict that the New Mexico native was on her way to becoming one of the most influential Hispanic women in broadcasting.

Sanchez begins the segment’s brief introduction.

Sanchez: Now to a spy thriller unfolding in the heart of suburban Los Angeles. The CIA allegedly brainwashes a woman and turns her into a sex slave to the rich and famous.

Chambers: It does sound bizarre. Jodi Baskerville is here with our Unit 13 exclusive investigation.

Baskerville’s voice can then be heard as aging photographs of a young woman — Brice Taylor, the subject of the special report — float across the screen.

Baskerville began her television news career in the South, reporting in Greenwood and then Jackson, Mississippi, in the mid 1980s. After a stop in Cincinnati, she moved to Los Angeles in 1990 and spent four years reporting and anchoring at KCBS. The L.A. Times questioned the wisdom of her subsequent decision to accept a position with the national show Hard Copy, a program subject to harsh criticism by the journalism community for its focus on celebrity foibles. But Baskerville explained that after losing her position at KCBS, the prospect of greater exposure and more than double the salary of typical local reporters made her decision an easy one.

Baskerville: Brice Taylor used to be your typical soccer mom, with a successful husband, three kids, and a beautiful home in the San Fernando Valley. That is, until she started telling of the secret double life as a mind-controlled sex slave for the CIA.

A glimpse of Taylor driving an automobile is replaced with what appears to be a pornographic film. An actress clad in a tight-fitting corset and fishnet stockings has apparently been hired by KCOP to display herself as if preparing to engage in sexual intercourse. She removes a gauzy, transparent robe while beginning to mount a bed, all the while facing away from the camera to conceal her identity. The soft-focus vignette is intended to provide a visual illustration of the news story. The actress has no lines to deliver. We hear Taylor instead, and then see the former housewife sitting in her home.

Taylor: I would have sex with him and deliver whatever messages that I was programmed to deliver.

The actress in the tight corset reappears, this time positioning herself so a generous view of her breasts fills the screen. The camera also lingers on the inside of her thighs as Baskerville introduces the rest of the story’s cast.

Baskerville: Now, this onetime suburban housewife finds herself the unlikely leading lady in a real-life psychosexual spy thriller costarring a former Los Angeles FBI chief…

The former FBI chief: Brice Taylor is absolutely telling the truth. I would stake my name and reputation of 50 years on it.

Baskerville: …a UCLA professor of psychiatry…

The UCLA professor: I’m sure she has no evidence that the CIA really is doing this.

Baskerville: …and a crusading psychologist.

The crusading psychologist: It’s what you read about — about the Holocaust — and what they did in the Nazi camps.

Glimpses of these characters are intercut rapidly with momentary views of the nameless actress’ thighs and stockinged feet. The sequence passes so quickly, the incongruent note of skepticism sounded by Dr. John Hochman, the UCLA professor, hardly registers.

Baskerville: If Brice Taylor’s story sounds more like a movie than reality, well, maybe that’s because it’s awful close to the plot of Long Kiss Goodnight. Just like Geena Davis, Brice is knocked unconscious in a near fatal car accident that jolts loose suppressed memories of another life as a CIA operative, seducing the rich, the famous, and the powerful from Washington to Hollywood.

Released in 1996, The Long Kiss Goodnight was directed by Renny Harlin from a Shane Black script. Roger Ebert says of it: “The movie is Hitchcockian in its use of famous locations.” He gives it two and a half stars out of four.

Taylor: All of a sudden I’m in bed with some, you know, politician or different Hollywood actor or comedian.

Baskerville: And even American presidents.

Taylor: My program assignment was to strip, to swim with the president, and then to have sex with him later on in the evening.

Baskerville does not ask Taylor to identify which politicians, presidents, actors, or comedians she was programmed to sleep with. Taylor is more expansive in her writings and on the telephone.

“A lot of these very famous people own mind-controlled people, and Bob Hope bought me when I was a very little girl at a slave auction,” she tells New Times. Taylor — whose real name is Susan Ford — lives in South Carolina, where she runs something called the Brice Taylor Trust, which distributes her books.

Taylor says Hope loaned her out to such luminaries as Henry Kissinger and every president after Eisenhower except for Carter and the elder Bush, whom Taylor calls a pedophile, accusing him of sleeping with her young daughter. Asked how she could corroborate these claims, she says, “I’ve identified a lot of penises. And I could also tell about the way that they preferred sex. Some of them are into really violent, kinky sex, and some of them acted like kids. Some of them were real passive, like Reagan.”

She only came to realize that all this was being done to her, Taylor says, after an April 1985 head-on collision that sent her headfirst through the windshield of her car. Taylor denies that the accident caused her brain injury; she remembers instead that her mind was filled with a rush of strange memories. After struggling with the memories for two years, she began therapy that helped her remember her enslavement to presidents, including her first White House master, John F. Kennedy. Taylor was 12 years old when JFK was assassinated in 1963, so her sex slavery must have begun at quite a young age. And it continued for decades, she says, even after her postaccident therapy had begun.

If her long career seems remarkable, the 49-year-old Taylor explains that her mind-control masters were able to place her in a state of suspended growth, so that she did not begin to age at a normal rate again until she started the process of healing.

For some reason, Baskerville, who at 42 is staring squarely at middle age herself, does not remark on this startling discovery of CIA aging-control.

Baskerville: Have you ever considered the possibility that you’re just crazy?

This is the first indication that anyone at KCOP might have reservations about Taylor’s being a presidential sex toy owned by Bob Hope.

Taylor: I absolutely thought I was crazy initially.

After accepting her job with Hard Copy in 1994, Baskerville enjoyed a few years of national semicelebrity before her career began to stall amid a series of embarrassing incidents. In 1995, however, she was still on something of a rise, and Essence magazine featured the reporter in a short piece about what products she used on her hair and skin.

We now see Taylor walking in front of some kind of building wearing a determined look on her face. Baskerville, meanwhile, shakes off her moment of doubt and again adopts the tone of a serious journalist promoting a sound theory.

Baskerville: Now, more than 10 years and countless psychotherapy sessions later, Brice and a band of supporters are convinced she was indeed the victim of covert CIA mind-control experiments.

KLAC-TV, Los Angeles’ third television station, began broadcasting on September 17, 1948. Six years later, after it was sold to the Copley Press, the station changed its call letters to KCOP. The station’s archivist, Mitch Waldow, describes early newscasts that featured hard-bitten journalists who had a passion for covering significant news events. Then, too, professional wrestling was a staple, but news was taken seriously. Reporter Clete Roberts set the standard in the early 1950s with his passion for breaking action. In outtakes from a 1952 Malibu fire, Roberts can be seen helping people move to safety.

“You can see how he’s like a kid, helping people moving furniture out of their homes, helping them get out of the hills and then interviewing them when they’re safe. He had a real public-service idea of what being a reporter was supposed to be about,” Waldow says. The archivist recites a list of legendary names from KCOP’s past, like newscaster Baxter Ward, who later became a county supervisor.

“I can’t say that people ever thought of us as the first place to turn,” Waldow says, acknowledging that KTLA Channel 5 had come first and that the network-backed stations eventually dominated the market. But the smaller independent station at the end of the dial still knew how to cover the big story.

“For us it’s been a series of highlights over the decades,” he says.

Waldow goes through a list of key events that KCOP, like the other local stations, went after with everything it had: Former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s L.A. visit, the 1960 Democratic National Convention, Marilyn Monroe’s death, RFK’s assassination, the kidnapping of Patty Hearst, the Manson trial. In 1961 Hal Fishman, then a KCOP reporter, was sent to cover the building of the Berlin Wall, and the station devoted a full hour to the event. By the late ’70s, however, the tide had begun to turn, Waldow says, and all of the local stations, following the lead of Tawny Little-anchored Eyewitness News on KABC Channel 7, jettisoned political coverage and a serious news focus for an increasingly lurid obsession with crime, car crashes, and celebrity news. As late as 1979, Waldow remembers, KCOP still devoted nearly an entire program to a single, important political story: The protests of Iranian students over the leasing of a Beverly Hills estate by the Shah’s sister.

In 1960, KCOP was sold to Chris-Craft Industries Inc., which is seeking federal approval to sell the station to News Corp., which owns the Fox television network. Waldow, a 17-year KCOP veteran, talks optimistically about regaining some of the station’s former glory after its sale.

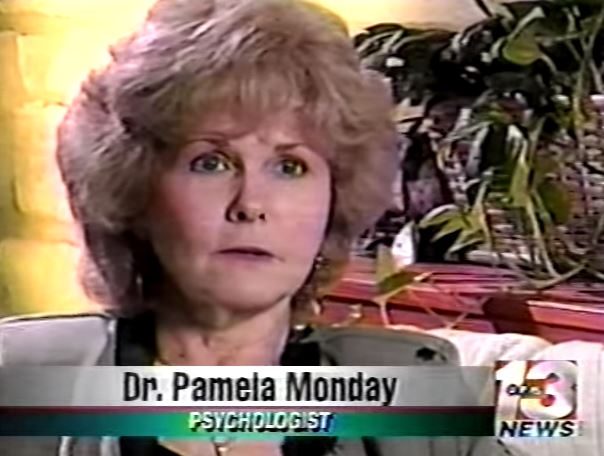

Baskerville now introduces Dr. Pamela Monday, an Austin, Texas, psychologist who says she is “treating 60 other women telling the exact same story as Brice.”

Monday: If Brice was the only person who I had heard those stories from, then I would say this has surely got to be crazy.

Monday received her Ph.D. from the University of Texas and sits on the board of the Texas Marriage and Family Therapy Association. But she rarely discusses her work on mind control and satanic cults with her professional colleagues.

“They think you’re crazy,” she tells New Times. “Well, I’m sorry, this is the most fascinating material and the most exhilarating thing when you can help people with it.”

Monday says that helping CIA mind-controlled people is only a small part of her overall practice, but she’s been treating such patients for more than a decade. Early on in that period, Monday says, she learned that asking some of her patients the questions “What is alpha?” and “What is beta?” seemed to trigger reactions in them. Encouraging patients to explore those reactions, she eventually unraveled complex layers of mind-control programming that had resulted from years of trauma. Her patients recovered memories that satanic cultists had ritually tormented them as children, an experience that caused them to develop multiple personalities, or “alters,” which crowded their subconscious minds. CIA mind controllers later programmed these alters using drugs, electric shock, and other forms of torture. Monday learned that the alpha alter was the one patients presented to the world, while betas were sex slave alters (nearly all of her mind-control patients and the patients of other therapists undergoing similar treatment are middle-aged white women), and deltas were assassin alters. Monday found many other alters the more she dug into her patients’ minds.

Most of Monday’s family-therapy patients complete their treatments in three months or less, but for her mind-control patients, getting to the deepest, darkest layers of satanic and CIA abuse can sometimes take eight or nine years of deprogramming. Recently, however, she has learned how to speed that process up somewhat.

She’s found that her patients have also been implanted with “screen memories” to make them forget their work for the government. In many of them, these screen memories include false experiences of alien abduction. CIA mind-control experts install the alien memories so that when sex slaves tap into them and begin telling others about their experiences, they sound insane. “It makes them look crazy in order to cover up what the real programming is,” she says.

Unfortunately, soon after Monday successfully decoded the alters, her patients failed to respond to questions about alphas, betas, and deltas. She could only conclude that the CIA mind controllers had realized she was closing in on their secrets, and had changed the parameters of their programming. Several times she and her patients have come close to exposing the actual programmers, who Monday believes include seemingly respectable medical doctors and church officials. One of Monday’s patients convinced police to search an Austin house she said was being used by CIA programmers posing as church leaders, but by the next morning, when a policeman served a search warrant, the place had been completely cleaned out. Even the rug had been removed, Monday says. “These people are highly connected,” she warns.

After 10 years of talking to patients who claim to be kidnapped on a regular basis by men in suits driving white vans who take them to secret locations to be shocked, prodded, and programmed, Monday cannot point to a single piece of physical proof that these events are actually happening.

“I don’t have the time to gather the proof. I’ve got to work on healing these people,” she says.

Monday: It is the worst abuse of human beings you can possibly imagine.

In 1992, Monday did her part to put two suspected satanic cult leaders in prison. She advised prosecutors as they tried the case of Fran and Dan Keller, two Austin day-care center operators who had been accused of ritually abusing and programming young children at Fran’s Day Care. Based on what children told their parents and therapists, the Kellers were accused of dismembering people with chain saws and stuffing their skins into the children’s socks, cutting out an infant’s heart and placing it in the hands of other children, burying children alive, shooting children and then bringing them back to life, kidnapping a gorilla from a zoo that didn’t exist, and flying the children to Mexico for physical abuse but returning them in time to be picked up by unsuspecting parents. Prosecutors actually tried the Kellers for a single instance of alleged sexual molestation.

Monday says she hovered near prosecutors during the trial, handing them questions to ask defense witnesses. Her mentor, psychologist Randy Noblitt, created a stir when he accused Dan Keller of attempting to mind-control the child victims from the defense table. Noblitt, Monday says, used a courtroom videotape to show that when the children were on the witness stand, Keller held his hands near his face and neck in particular ways — Monday remembers Keller holding one of his hands in a C shape against his face — which Noblitt explained were satanic signals that the kids would be killed if they continued to testify.

Asked if Noblitt’s testimony had an impact on the jury, Monday says, “It was pivotal. Pivotal. You could see the signs right there on the video monitor.”

Fran and Dan Keller were each sentenced to 48 years in prison.

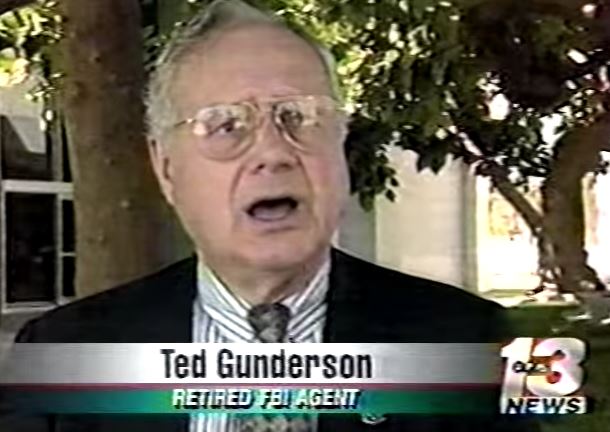

Baskerville: Then there’s Ted Gunderson, a special agent in charge of the FBI’s Los Angeles division until he retired in 1979.

Gunderson: Mind control has been in this country since the late 1940s.

Baskerville: Gunderson has obtained numerous declassified documents to support his claim, including a finding by a Senate investigation that the CIA has indeed conducted mind-control experiments on unwitting American citizens.

Gunderson: It’s mind boggling. I happen to have 2,200-plus pages of documentation of the mind-control program.

Documents in Gunderson’s collection appear only briefly on the screen, but long enough to identify them as declassified “MK-Ultra” records.

In 1977, a Senate committee chaired by Ted Kennedy investigated the CIA’s secret mind-control experiments, primarily involving LSD, which were carried out under the code name MK-Ultra. In the 1950s and ’60s, a man named Sidney Gottlieb directed the studies, sometimes using unwitting human subjects, including the mentally ill, prostitutes, and drug addicts. At least one person died as a result. The experiments, which have been roundly condemned, were a clear violation of the Nuremberg Code, which was issued after the World War II war-crimes trials and prohibits experimentation on human subjects without their consent. The unfortunate soldiers and civilians chosen for LSD testing had reacted in many different ways, and some suffered permanent damage. But Gottlieb ultimately gave up the program when it became clear that the hallucinogen made subjects less controllable. In 1973, shortly before his retirement, Gottlieb concluded that his experiments had been a total failure and waste of time. (No documentation has been found that links Brice Taylor with the long-ended MK-Ultra program.)

Baskerville, meanwhile, makes no mention of Gunderson’s colorful history as a longtime promoter of conspiracy theories involving black helicopters, ritual slayings, and CIA mind control. Since his retirement from the FBI in 1979, Gunderson has focused on what he characterizes as a satanic cult movement of epidemic proportions.

Gunderson tells New Times that in 1970, 500 satanic cults were operating in the New York area alone. (In a 1996 lecture, Gunderson told an audience those groups averaged eight ritual slayings per year, which would mean the annual disappearance of 4,000 New Yorkers.)

Today, Gunderson says, the number of cults in the New York region has mushroomed to 2,500. In L.A.’s South Bay, meanwhile, 3,000 people — more than 1 in 100 — are satanists, he claims. And Gunderson estimates that, across the country, 4 million Americans are active participants of devil-worshiping cults that carry out ritual murders.

“They’ve infiltrated every level of society. Prosecutors, cops, the CIA, the FBI, city councils, county governments, elected officials. It’s the most gigantic cover-up in the history of the world,” he says.

Today, Gunderson says he can’t get the FBI to return his phone calls. He’s even been kicked out of a society for former agents.

“So be it. I’m right and they’re wrong.”

Baskerville: Brice alleges that she and her entire family were among the victims of that MK-Ultra program, conducted at military bases and major hospitals across the country including Los Angeles. Brice claims that the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute here in Los Angeles was used by CIA-controlled doctors as a chamber of horrors where both she and her father were subjected to diabolical mind-control and brainwashing experiments.

Gunderson: Drugs. Hypnosis. Electroshock. Torture.

Gunderson is also noted for contributing to the early retirement of radio host Art Bell. For two years, Gunderson hosted a shortwave radio program, and in 1997 one of his guests made unsubstantiated claims that Bell was a child molester who had been able to cover up his crimes. Bell angrily denied the allegations. Earlier this year, Bell retired from his radio show, citing stress associated in part with the accusations on Gunderson’s program.

Gunderson says he later learned that his guest had mixed up several facts about an actual case of molestation involving an Art Bell. But that Bell was the radio host’s son, and he’d been victimized by a substitute school teacher.

Bell sued Gunderson, the guest, and the shortwave radio station. Gunderson says the case has been settled. “Bell blamed it on me, but it was really blown out of proportion,” he says. “It did taint my name and reputation to a degree.”

Baskerville: And Brice says it turned her into a mindless “Stepford” wife, a programmed sex toy who could be triggered into action by the CIA with subliminal messages embedded in her brain.

Taylor: I was a human robot, who had no ability to think or question on my own. I could only follow commands.

Baskerville doesn’t mention that Taylor believes she received her CIA instructions through subliminal messages in Disney films. Taylor claims that many CIA-controlled Americans receive messages through Universal’s 1939 film The Wizard of Oz.

The former sex slave was only able to escape this programming, she says, after she reintegrated 188 distinct personalities.

Baskerville: Brice, now 49, says she was just one of thousands of mind-controlled sex slaves known to the CIA as “presidential models,” programmed to seduce and gather intelligence from powerful men without ever remembering a thing about it.

Taylor: I had no idea because I was programmed to consciously only know that I was, you know, doing my motherly, housewife duties.

In 1993, L.A. Times television columnist Howard Rosenberg wrote that Baskerville’s journalistic bumbling almost cost a woman her life. Baskerville taped a story from the living room of a San Pedro woman who was terrified by drug dealing going on outside her apartment. Rosenberg pointed out that although Baskerville seemed to be protecting the woman’s identity, she wasn’t doing a very good job of it.

“From the position of the camera, it would be obvious to anyone seeing the story exactly where the woman lived,” Rosenberg wrote. Baskerville also gave the woman’s age and occupation and showed the color of her hair. Hours after the piece ran, someone heaved a Molotov cocktail into the woman’s apartment. Luckily, it didn’t explode.

Baskerville’s exposure on the national journalism scene was relatively brief. Negative publicity began to dog the reporter after her move to tabloid television in 1994. In the wee hours of a July 1997 morning, she lost control of her Jeep Cherokee and hit a parked car. A gash in her head took 10 stitches to close. Police found that no drugs or alcohol were involved and did not file charges. A year later, Baskerville ended her job with Hard Copy and began short stints at The Travel Channel and EXTRA.

In 1999, the New York Post reported that Baskerville missed three weeks of work because of unspecified “legal troubles”; left over from a restraining order a boyfriend had taken out on her years earlier. Saying that Baskerville “has a history of erratic behavior,” the Post explained that the former boyfriend had asked for the restraining order after Baskerville assaulted him, kicked in the French doors at his residence, and slashed his pickup’s tires because he refused to see her anymore. In a phone interview with New Times, Baskerville insisted the Post story was “inaccurate,” but when asked to explain, she hung up.

Six years after leaving L.A., Baskerville once again became a local reporter, joining KCOP six months ago.

Baskerville: Yes, it’s strangely similar to another movie, The Manchurian Candidate. How could they do this without anyone noticing?

Taylor: Um, my husband was also programmed.

Baskerville: And so were their children, Brice says, including her beautiful young daughter, Kelly.

KCOP’s news director, Larry Perret, arrived at the station earlier this year after a five-year stint with KCBS, where he was credited with helping the station improve its fortunes. In 1998, the L.A. Times wrote that Perret had hit upon special investigative reports as a way to prop up the flagging ratings of the station’s eleven o’clock news.

Perret brought his idea of featuring such investigations to KCOP. Earlier this year he told Electronic Media: “Really great TV stations will do investigative reports that are responsible and well researched. It benefits the viewer, and that’s what we’re here to do.”

Taylor: Sometimes we were even programmed to be a mother-daughter sex team.

Although Taylor says she was employed continually over several decades as a sex doll and human message machine by Hope, Kissinger, six U.S. presidents, and even Sylvester Stallone — who she claims sexually abused both Taylor and her young daughter in a Hawaiian threesome — she acknowledges that she doesn’t have so much as a single photograph to prove she was ever in the presence of any of them. She hopes that her most recent book about her experiences will prompt others who have such photographs to send them to her.

Baskerville: Whether it’s true or not, Brice’s story has had a tragic effect on her once happy family. She and her husband are now divorced, and her two grown sons have virtually disowned her.

Taylor: Well, my ex-husband and my sons think that I’m absolutely crazy.

This is certainly true. In a recent court hearing, Taylor’s husband described the lunacy Taylor put her family through following her 1985 car accident. During Taylor’s seven-days-a-week therapy, she recovered memories that she had grown up in a family that was part of a satanic cult that subjected her to outrageous acts of sex and violence, including forcing her to drink the blood of infants.

Her husband described the severe financial and emotional strain Taylor’s therapy put on the family as she began to insist that all of them had been through CIA programming. Her husband did what he could, even participating in a therapy called “reparenting” that involved treating Taylor as if she were an infant. “I spent hours rocking Brice in a rocking chair with a baby bottle and a pacifier,” he testified. In 1991, when the family ran out of money for Taylor’s therapy, she insisted that her husband sell their house to pay for it. When he didn’t, she left.

Baskerville: Kelly was the only one who believed her mother’s story, and suffered a complete nervous breakdown over it.

Baskerville apparently relied on Taylor for this assessment, but court transcripts in San Diego suggest a very different story. On June 21 and 22, Superior Court Judge Patricia Yim Cowett presided over a trial in San Diego’s central courthouse to determine whether to declare Kelly gravely disabled mentally and assign a county conservator to take over her care.

Kelly was described as having been severely mentally ill with schizophrenia for several years. She had made two suicide attempts in her teens, and had become uncooperative and unpredictably assaultive as an adult, requiring her to need 24-hour care in a locked facility. (Kelly’s father supported the county’s legal attempt to take over her care.)

Dr. Raymond Fidaleo, who examined Kelly when she was admitted to Sharp Mesa Vista Hospital early this year, witnessed Kelly become agitated during a meeting with her mother. When Taylor began to explain to Fidaleo that she and her daughter had been victims of CIA mind control, Kelly got up and walked out.

Fidaleo said that Taylor believed Kelly would not get better until she “owned up” to her past as a CIA sex slave. But Kelly doesn’t believe her mother’s assertions, Fidaleo testified: “She was angry with her mother for trying to tell her this happened to her, that indeed it didn’t happen. And she was adamant that she’d never been programmed or never been sexual with people the way the mother had said.”

Taylor: Kelly actually made two suicide attempts.

Baskerville: And now, at age 22, Kelly is in a catatonic state in a California mental hospital after being committed by a judge just last year.

The hearings before Judge Cowett last June — not last year — may have been among the strangest ever conducted in a San Diego courtroom.

Arguing against the county’s plan to put Kelly in a locked facility for the next year, attorney Roy Short put on a series of witnesses in an effort to convince the court that Brice Taylor should be allowed to take over care for her daughter.

Short’s first witness was Ted Gunderson.

The former FBI agent explained to Judge Cowett that since his retirement he had learned of a worldwide, centuries-old satanic conspiracy operated by a “shadow government” that has included financiers, newspaper owners, and German Nazi scientists who infiltrated American government agencies after World War II. Gunderson testified that he became convinced that Kelly had fallen under the conspiracy’s programming when he noticed the way she looked at him, as if she were waiting for him to “trigger her.” Gunderson explained that Kelly was looking for the signal that would launch her CIA programming and turn her into a prostitute or assassin.

Gunderson noticed this, he explained, when he spent approximately two months sleeping on the couch of an apartment Taylor had rented last year in Las Vegas. Taylor had suddenly relocated there from Los Angeles after she received a threat, and Gunderson agreed to provide security to her and her daughter. (Taylor says the threat occurred in a theater during a movie, when she felt a sudden blast of pain at the base of her skull. She first thought she was having a stroke. At the same time, she says, Kelly began screaming and ran out of the theater. Taylor says she then realized they had been the victims of an attack of “targeted energy” by unknown assailants. She immediately abandoned her apartment and took Kelly to Las Vegas.) During this time, Gunderson testified, a deprogrammer was brought in to help Kelly, but the deprogrammer turned out to be a double agent working for the CIA.

Other witnesses provided similar if less colorful testimony. Taylor herself asserted that she had been providing 24-hour care for Kelly for years and wanted to continue doing so. But testimony by several witnesses painted a less sanguine portrait of Taylor’s parenting skills. Taylor’s own mother and others testified that at one time, fed up with Kelly’s unpredictable behavior, Taylor put her unattended schizophrenic daughter on a South Carolina-to-L.A. flight, and didn’t arrange for anyone to meet Kelly at LAX until the plane was on its way.

On June 23, Cowett formally found that Kelly was gravely disabled and named the county her conservator.

Since that time, Gunderson has waged an Internet campaign against the decision, warning readers that Kelly is vulnerable to being put to death by the CIA while she is under county control.

Taylor: My fear is that she will be harmed while she’s in this institution.

During this portion of the program KCOP shows two disturbing photographs of Kelly drooling on herself. The pictures were apparently supplied by Taylor. There’s no indication that Kelly herself approved their being shown to the public.

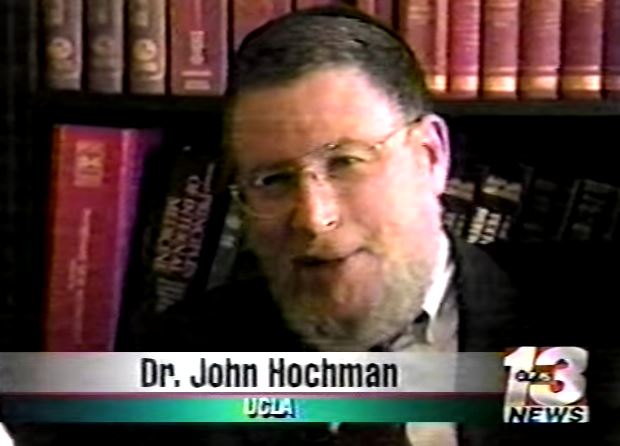

Baskerville: Even Dr. John Hochman, an assistant professor of psychiatry at UCLA, doesn’t doubt Brice is convinced what she is saying is true.

Hochman is not actually a member of UCLA’s paid faculty. According to the psychiatry department’s personnel office, he donates 50 hours or more each year to supervise students. This volunteer work entitles him to the designation “assistant clinical professor.”

Hochman: She could be a great actress and just be scamming everybody. That’s possible. But my take was that she believed what she was saying.

Baskerville: Including Brice’s claim that she was brainwashed by the CIA at Hochman’s very hospital.

Hochman: UCLA is the biggest hospital west of the Mississippi, so I don’t know what’s going on in every laboratory, every patient room, every closet, every corridor.

It may be difficult for Hochman to keep an eye on everything happening at the hospital since he doesn’t actually work there. His office is in Encino.

Baskerville: However, Dr. Hochman suspects that Brice is not a victim of CIA mind control but of a strange condition known as false memory syndrome, in which delusions are unwittingly reinforced and sometimes even implanted by psychotherapists themselves.

Hochman: Many of the cases in recent years that have caused problems have been the result of psychotherapists. They didn’t really understand the power of the techniques and the way techniques can make things go wrong.

This is the first suggestion in Baskerville’s story that there might be an alternative theory to explain Taylor’s delusions — that they had been suggested to this troubled woman by irresponsible therapists.

Baskerville comes up with a clever way to dodge this competing idea. A quick cut shows the reporter’s hand putting down a telephone receiver to help her emphasize the next point.

Baskerville: We contacted three Los Angeles psychotherapists who treated Brice, but all of them refused to discuss her case, even with her permission.

This is quickly followed by the image of Monday picking up her telephone receiver with a smile for the camera, completing the visual implication for KCOP viewers: Brave therapists answer Baskerville’s phone calls. Fearful ones don’t.

Baskerville: Pam Monday believes that’s because they’ve already been threatened by the CIA.

Monday tells New Times that she never made any claims to KCOP about therapists receiving CIA threats. “That’s ridiculous. How would I know that?” Monday says.

Monday points out that she never actually spoke to Jodi Baskerville — KCOP asked a film crew from Austin’s KXAN Channel 36 to film her. Monday says the KXAN reporter who interviewed her knew almost nothing about the background of the story.

Monday had originally been contacted for the story by Taylor, who told her that the EXTRA show was interested in doing a program about CIA mind control (the two women had met at conferences where both were featured speakers). Monday says she was reluctant to participate because of EXTRA’s reputation for “T and A,” and because of what she characterizes as disappointing experiences with journalists in the past. But Taylor convinced her to cooperate with the EXTRA producer, Wayne Darwen.

Several weeks later, Monday heard from Darwen that EXTRA had gotten “cold feet” about the story because of its speculative nature. But in mid October, the project was back on after Darwen took the story to KCOP.

“Mysteries, conspiracies. That’s pretty much what I do,” Darwen tells New Times. “I have a real low boredom threshold. I need the real wild shit to keep my attention.” The veteran freelance producer complains that TV tabloid shows have gone soft in recent years under pressure from advertisers, but local television news programs are becoming more open to his work. Baskerville and Kristin Lang, KCOP’s executive producer of special projects (including Unit 13 investigations), are both veterans of TV tabloid shows, he points out. “Local TV is more tabloid than tabloid right now,” he says.

Taylor and Monday both say Darwen was motivated to do Taylor’s story because of the guilt he feels since he did a piece for EXTRA about Illinois psychiatrist Bennett Braun.

In the late 1980s, Braun was one of the nation’s leading proponents of recovered memory therapy. He had come under investigation by Illinois licensing authorities largely because of revelations about his treatment of a patient named Patty Burgus. According to a lawsuit filed by Burgus, Braun had used hypnosis and drug therapy to convince her that she had 300 personalities, ate meat loaf made of human flesh, and was the high priestess of a satanic cult. In a 1999 settlement with Illinois officials, Braun’s license to practice medicine was suspended for two years and he agreed to five additional years of probation.

Darwen regrets that his EXTRA piece ridiculed Braun’s theories about satanic cults and multiple personality disorder. He now believes Braun may have been right, that Burgus was in fact the victim of a nationwide network of satanic cults.

Asked why the KCOP program about Brice Taylor didn’t include her more outlandish claims — assertions about receiving mind programming through Disney movies or having her aging slowed by the CIA, for example, which might have made her appear less credible — Darwen says he didn’t have time to include them. Also, he left out names like Bob Hope and Henry Kissinger because he wanted to avoid libel issues. “I didn’t think it was fair to put up famous names when there was no evidence,” he says.

That lack of evidence, however, didn’t prevent KCOP from airing a piece that claimed Taylor was an unwitting sex slave.

“It makes for a really interesting story. Do you want to tell an interesting story or a boring one?” Darwen asks. “It’s not up to me to decide who’s telling the truth here.”

Monday: There is no such thing as false memory syndrome. There’s nothing in the diagnostic statistical manual that says there is such a thing.

In 1992, several Philadelphia-area parents established the False Memory Syndrome Foundation to combat what they contended was a psychotherapy movement out of control. Since then, therapists who engage in recovered memory therapy have endured waves of negative publicity, causing many of them to cease their inquiries into satanic cult abuse.

But a hard core of adherents like Pamela Monday continues the practice, says Dr. Richard Ofshe, the University of California, Berkeley, sociology professor known as one of the movement’s harshest critics.

“Recovered memory therapists are sort of like a virus. They have the potential for coming back,” he says.

Baskerville: In fact, Dr. Monday claims false memory syndrome was actually concocted by the CIA to cover up its mind-control experiments.

“I didn’t tell her that,” Monday says.

Baskerville: Are you CIA?

Baskerville asks this of Hochman, the Encino psychiatrist, while suppressing a grin. Hochman responds in kind.

Hochman: As far as I know, I’m not CIA. Maybe they know I’m CIA. But I don’t know.

New Times asked Hochman his opinion of the way KCOP used him to bolster its story.

“I thought it was kind of sensational the way they did it,” he responds, sounding about as perturbed as if he’d noticed his shoe was untied.

Baskerville: Meanwhile, Brice Taylor remains convinced that her memories are tragically real.

Taylor: I definitely believe this is still going on, and I believe it will continue to go on until it’s exposed and stopped.

Throughout the segment Taylor has spoken in a monotone while wearing a glassy stare. Every day, reporters get phone calls from men and women like Brice Taylor who struggle to make sense of their labyrinthine delusions. Journalists rarely consider their convoluted tales newsworthy.

Baskerville: Brice Taylor wrote about her alleged life as a CIA sex slave in vivid detail in a new book out called Thanks for the Memories.

According to Darwen, Taylor’s story received a record rating for KCOP’s news program, reaching more than 250,000 households.

The program’s executive producer, Kristin Lang, says it should have been obvious to viewers that Taylor was mentally disturbed.

“I think it was presented as a medical mystery. I don’t think it was presented as anything more than that,” she says. She disagrees when asked if the station withheld key information about Taylor, Gunderson, and Monday in order to make Taylor’s claims about mind control seem more legitimate. Lang says the piece was about Taylor’s mental illness, not her alleged career as a sex slave.

News director Larry Perret reacts angrily to the suggestion that KCOP had held back Taylor’s more outrageous claims in order to make her seem more believable.

“To suggest that we’d be anything but honest is insulting,” he says.

Back in the studio, Baskerville and the anchors shake their heads, appearing deeply moved by the story they have just aired. Baskerville turns to Chambers and Sanchez for the payoff.

Baskerville: Believe it or not.

Chambers then utters a telling remark. He clearly has no idea whether the story his station has just put on the air has any basis in truth, but he knows how he feels about it. In local television, this is an anchor’s main role.

Chambers: True or not I feel so sorry for the daughter. She seems like the victim in all this.

Chambers doesn’t know the half of it.The KCOP program’s last word goes to the pride of Albuquerque, the young woman who, it has been prophesied, will one day set the standard for Latina broadcasters everywhere.

Sanchez: A lot of questions still.

After a commercial break, the anchors will reappear to introduce a story about humorous outtakes from a UPN reality show, Blind Date, which follows the news program. In the days that follow, the station will air a segment about the decisions Sanchez faces when she buys maternity clothes for her first pregnancy. Another story asks the station’s makeup artist to compare different brands of cosmetics by applying them to Baskerville’s face.

Earlier this year, the Associated Press named KCOP’s news program the best one-hour broadcast in the state of California.