[Retired Cal State Long Beach professor Kevin MacDonald has become a pretty notorious source of inspiration to the “alt-right” movement, but when we wrote about him in the year 2000, he was virtually unknown outside of a few academics. In 2002, however, the newspaper our story appeared in went out of business, and this story disappeared from the Internet. With so much more interest in MacDonald today, we thought it might be a good idea to bring this piece back. MacDonald himself hosted links to this story at his own website, along with his criticisms of it. Also, for a recent story refuting the IQ data that MacDonald relies on, this lengthy piece at the Guardian is another good piece putting this material in some context.]

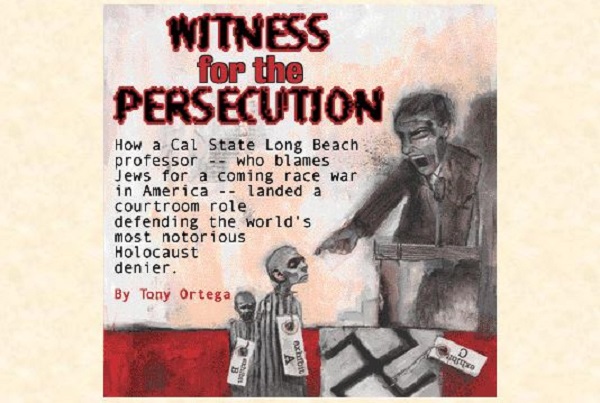

WITNESS FOR THE PERSECUTION

How a Cal State Long Beach professor — who blames Jews for a coming race war in America — landed a courtroom role defending the word’s most notorious Holocaust denier

(Originally published April 19, 2000 in New Times Los Angeles)

Last Tuesday morning, Kevin MacDonald didn’t sound like himself. Normally affable in a reserved sort of way, the Cal State Long Beach psychology professor was barely audible when speaking on the telephone from his Laguna Hills home. He sounded depressed and irritable. “I’m in a bad mood,” he warned, and blamed it on that morning’s monumental news.

Half a world away, a British judge had labeled historian David Irving a racist and an anti-Semite.

Irving had sued American Professor Deborah Lipstadt and her publisher, Penguin Books, saying that she had libeled him in her 1993 history of Holocaust denial. Irving — who claims there were no gas chambers at Auschwitz and that Jewish deaths at the hands of Nazis totaled closer to one million than six million — accused Lipstadt of damaging his reputation by suggesting that he had falsified history in his books. But in a 334-page decision, Judge Charles Gray agreed with Lipstadt that Irving had distorted facts to fit his bigoted views. Gray found for the defendants and ordered that Irving pay their legal costs, which Penguin Books estimated at more than $3 million.

Holocaust scholars and Jewish groups greeted the verdict with exultation. So badly had Holocaust historians wanted to see Irving defeated that the state of Israel had been persuaded to open Adolf Eichmann’s carefully guarded prison diary to the public. Several of the world’s most prominent Holocaust scholars had helped the defense and battled Irving over his interpretation of Nazi documents.

Irving himself had presented only two expert witnesses. One was Cal State Long Beach Professor Kevin MacDonald.

MacDonald doesn’t share Irving’s doubts about the Holocaust; in fact, he makes no claim to be an expert on the subject at all. Instead, Irving asked MacDonald to testify because of his controversial ideas about Jews and their DNA.

An evolutionary psychologist, MacDonald asserts that Jews do better on IQ tests because, for millennia, they have practiced what amounts to a eugenics program disguised as their religious code. That’s made them not only smarter, but better competitors in the Darwinian struggle for survival — which in turn has produced hatred and jealousy toward them among non-Jews. Anti-Semitism, in other words, is not an irrational hatred of Jewish people but a scientifically understandable by-product of Jewish success.

Nazis, MacDonald argues, reacted to that Jewish success by mirroring Jewish strategies such as emphasizing collective identity — an argument that MacDonald admits puts at least part of the blame for the Holocaust on the Jewish victims themselves. MacDonald says that Jews have responded to anti-Semitism in various ways, including usurping Western culture’s intellectual movements and using them to denigrate Gentile society. In the final chapter of his trilogy on Judaism, MacDonald predicts that the Jewish program of attacking Gentile values will eventually, in the United States, trigger ethnic warfare.

When New Times first contacted MacDonald after he returned from the trial, he turned down a request for an interview. Nothing had been written about him in local newspapers, and he wanted to keep it that way. “I don’t want protesters outside my office,” he said.

But choosing to testify in the Irving trial considerably increased his notoriety. Several academics have already begun collaborating on a book about him. His professional colleagues plan to debate his ideas at an annual conference in June. The Anti-Defamation League says it’s currently investigating MacDonald and intends to put out a report on his books.

Various right-wing hate groups that maintain Web sites, meanwhile, laud MacDonald and have spread the word about his theories. MacDonald says it doesn’t please him that neo-Nazis have been attracted to his views, but he vigorously defends his ideas in academic discussions on the Internet, where they seem to be under constant attack. He insists he is an objective scientist and not an anti-Semite.

Despite his inclination to remain obscure, MacDonald is becoming infamous. Told that a story would proceed with or without his help, he relented and invited New Times to observe one of his lectures. But now, 10 weeks after his involvement in Irving’s trial, MacDonald was despondent.

“So I imagine this article will come out quickly, then?” he asked, sounding like he’d come to regret his cooperation. It was apparently dawning on him that he’d backed the wrong horse in a contest watched by much of the world, and the effect on his career could be devastating.

“This is going to be a disaster, I know,” he said.

For a decade, the new science of evolutionary psychology has enjoyed surprisingly good press. The public seems to love the discipline’s inventive Darwinian explanations for every quirk of human nature, from why men chase skirts to why women insist on asking for directions.

For every social or psychological idiosyncrasy, the evolutionists seem ready with an exegesis from our Pleistocene past.

Why is it that American marriages seem most vulnerable to divorce in their fourth year? The Darwinian answer: On the African savanna eons ago, a four-year-old child had grown sufficiently that a mother no longer had to be dependent on a male to bring her food; she could go out and gather both her own food and a new mate.

Why are men more easily aroused by photographs of naked members of the opposite sex? Evolution’s solution: On the primordial plain, a male’s ability to judge a female’s fertility — and her likelihood of passing on his genes — relied on his ability to judge her physical appearance.

Why do some parents seem to refute Darwinian goals by killing their own children? Natural selection’s thesis: In the harsh ancient environment that produced the first humans, lame or mentally defective children might have been sacrificed rather than have lives that would have been snuffed out anyway prolonged. Or a mother with too many children or insufficient aid from an unhelpful mate might have cut her losses by letting a healthy baby die.

So goes the evolutionary way of looking at things: Ancient habits that gave early humans a survival edge became stamped on their DNA. They became as much a part of the human genome as an upright walk and opposable thumbs.

However, the new field has plenty of critics who say there’s little hard evidence to support such explanations.

These spoilsports allow that it may be safe to credit natural selection with a general urge to procreate. But who you decide to settle down with or why you choose to get a divorce are decisions fraught with questions about how you were raised, who your parents were, and what sort of customs your society values. In such decisions, genetic urges get overwhelmed by cultural forces.

For such critics, evolutionary psychology’s creative explanations for human behavior are little more than thought experiments that can’t be tested, since there’s no way to go back in time and see which behaviors really benefited early humans on that primeval savanna.

Moreover, say the new science’s detractors, evolutionary psychology isn’t really new at all.

Various experts say the “new” field is just a warmed-over version of a 1970s movement that fell into disfavor for its tendency to turn cultural prejudices into scientific “fact.”

Well before that, however, Darwinian explanations for human behavior were all the rage. At the turn of the last century, hereditary answers for what made people the way they are also held great sway. In fact, it’s hard to overemphasize how much heredity was believed to be the major influence on human affairs at the beginning of the 20th century.

After the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859, misreadings of the great work’s theory of natural selection resulted in “social Darwinism,” a political justification for exploitative treatment of the poor in the “survival of the fittest.” Darwin’s theory also inspired scientists — who were still years away from rediscovering Gregor Mendel’s studies of genetic laws — to look for clues to human heredity in superficial traits.

Researchers measured skull circumference, weighed brains, and gauged the distance between people’s eyeballs, hoping to find clues to what characteristics separated the bright from the dull, the virtuous from the venal.

Perhaps inevitably, researchers’ cultural prejudices colored their views of heredity. Sir Francis Galton — a cousin of Darwin’s — for example, believed he could determine the features of the essential Jewish face by photographing Jewish boys in an orphanage. The result was a composite that Galton believed showed the true “cunning” nature of the Jew. Galton is also credited with founding the modern eugenics movement, which by the turn of the century had a firm grip on the American mind.

The movement reached its peak in the U.S. in the 1920s and ’30s, resulting in severe limitations on immigration as well as sterilization laws. If poor genes were to blame for ignorance and crime, then preventing people of bad stock from reproducing or immigrating to the U.S. would benefit American society. Predictably, those judged inferior were most often the poor and nonwhite.

But the eugenics movement in America died after the revelations of the depths it had reached in Nazi Germany. In the wake of the Holocaust, Darwinian explanations for human behavior fell into disfavor, and were supplanted by Skinnerian ideas which suggested that people were born as blank slates and molded by culture. Nurture had won out over nature.

Then, in the mid-1970s, nature came roaring back. New gene-based explanations for what made animals cooperate with each other inspired scientists to wonder whether the same theories could be applied to human beings.

In 1975, Harvard’s E.O. Wilson brought together several of the new lines of inquiry and gave it the name “sociobiology.” His famous volume Sociobiology: The New Synthesis discussed human beings only in the final chapter, but that chapter set off a firestorm of controversy.

Two of Wilson’s Harvard colleagues, Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin, led the charge against sociobiology, calling it a right-wing and elitist attempt to legitimize the same theories of white male supremacy that had characterized the eugenics craze. They also called it unscientific, saying that speculating about life on the primeval plain was the scientific equal to Rudyard Kipling’s “Just-So Stories,” which conjured fanciful explanations for how the elephant got its long nose and the leopard its spots. Sociobiologists countered that Gould and Lewontin were leftist professors who wanted to suppress evidence that human beings were naturally predisposed to create hierarchical societies.

On the other hand, some sociobiologists did seem hell-bent on finding scientific rationalizations for their prejudices. In the face of the women’s movement, for example, Wilson and others appeared determined to justify male privilege by arguing that evolution had made women inferior.

In a famous episode, antiracist protesters dumped a pitcher of water on Wilson’s head while he was giving a speech. Largely through the efforts of Gould, Lewontin, and other scientists, sociobiology labored unsuccessfully to shed its image as a speculative, right-wing science.

For a variety of reasons, including new breakthroughs in DNA research, sociobiology has enjoyed a renaissance. Dubbed “evolutionary psychology” in 1992 by the UC Santa Barbara husband-and-wife team of John Tooby and Leda Cosmides, the field’s adherents stress that they won’t repeat the mistakes of the past.

“Any research is subject to criticism. The main difference, I think, between evolutionary psychology and sociobiology is that evolutionary psychology is better grounded in empirical research,” says University of Missouri psychologist David Geary. “So rather than just sitting around and thinking about what might have evolved, evolutionary psychologists and behavioral ecologists collect data derived from evolutionary predictions and test these predictions. It’s much more of an empirical discipline.”

Large bodies of research suggest that many basic tenets of the new science are on solid ground. It seems hard to deny that evolution bestowed different ways of thinking on men and women, particularly about sex. Anthropologists have found numerous behaviors that seem common to all human societies and likely the result of natural selection. And infants exhibit instinctive behavior that could not have been learned.

The events of the past few months, however, suggest that the new science may turn out as controversial as its earlier forms.

Howls of protest greeted the recent release of a book by two evolutionary psychologists, Randy Thornhill and Craig T. Palmer, who argue that rape is a behavior left over from natural selection — that men, in other words, are genetically predisposed to rape as a primordial strategy of creating more offspring. Their book, A Natural History of Rape: Biological Bases of Sexual Coercion, has been met with denunciations both from the feminist left and family-values right (and from some scientists who say the theory is simply preposterous).

Kevin MacDonald’s views, meanwhile, seem to be causing another, quieter panic in the field. When the online magazine Slate denounced MacDonald’s theories in January, John Tooby frantically denied not only that the Long Beach academic’s views were scientific, but that he could even properly be called an evolutionary psychologist.

Tooby’s words surprised some people in the field — MacDonald, after all, is the secretary-archivist of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society (HBES), the professional organization most closely associated with evolutionary psychology. Tooby is its president.

“It’s a strange thing for Tooby to say,” says Missouri’s Geary. “Kevin’s the secretary of HBES and obviously has been publishing in evolutionary psych for probably as long as Tooby has.” Geary says there’s no question that MacDonald is an evolutionary psychologist. He suspects that Tooby’s attempt to deny MacDonald’s involvement in the field was a public relations move. “I thought it was unprofessional,” Geary says.

He adds that he isn’t familiar with MacDonald’s trilogy on Judaism even though he’s very familiar with MacDonald’s other work and is currently collaborating with him on a paper about cognitive structures of the human brain. “I suspect most psychologists don’t know anything about that stuff. I mean, I haven’t read it,” Geary says.

Indeed, few scientists seem to have read MacDonald’s work on Judaism. But as his books gain notoriety and appear likely to give evolutionary psychology the kind of bad press that plagued its predecessor, leading lights in the movement say they’ll be taking a hard look at them. Tooby has promised to post on his Web site a detailed refutation of MacDonald’s ideas.

New Times attempted to ask Tooby why he denied that MacDonald was a member of the discipline, but Tooby did not return numerous calls.

MacDonald suspects there will be a showdown of sorts at the HBES annual meeting this June in Amherst, Massachusetts. “I will run for office again,” he says. “I think I’ll run again as a referendum and see what happens.”

Kevin MacDonald still remembers the crunching noise the wolf cubs made when they bit into the blind baby mice.

It was the late 1970s, and he was a graduate student at the University of Connecticut, studying the personalities of wolves. One of his tasks was to gather a number of wolf cubs into a large cage and climb up on top of it. Then he’d drop in a squirming, pink mouse and take careful notes on the feeding frenzy that ensued.

The purpose was to identify the most aggressive cubs. It wasn’t difficult to see which of them were more likely to push their neighbors out of the way for a rodent morsel. MacDonald monitored the cubs as they grew older and found that the aggressive ones stayed that way. Like people, the wolves had individual personalities that were stable over time. Aggressive cubs grew up to be aggressive adults.

The project earned MacDonald a Ph.D. and convinced him that genetic differences in animals affected their behavior. When he went to the University of Illinois to do postdoctoral work on child development, he assumed that the same kinds of inferences could be made about human beings. Today, he’s known among psychologists for his work researching early childhood behavior.

A professor at Cal State Long Beach since 1985, MacDonald works in one of the busiest departments at one of the busiest state colleges in California. He’s one of 55 full- and part-time professors who provide guidance to 1,200 psychology majors. Department Chair Keith Colman says MacDonald publishes more than a typical faculty member and points out that his colleague recently won an award for distinguished scholarship.

The accolades are nice, MacDonald says, but he really wanted to be a jazz musician.

Tall and lanky, the 56-year-old academic has a long, lined face and brown hair graying at the temples. He wears oval wire-rim glasses and doesn’t smile much, but he’s amiable. And when he breaks into a hoarse laugh, it’s usually at his own expense.

He grew up in a traditional Roman Catholic family in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, and attended Catholic schools before heading off to the University of Wisconsin. His aim was to become a jazz pianist, but he says he soon realized that he was no Chick Corea. Instead, he fell into the campus counterculture and became a radical in the antiwar movement. His involvement provides the first clue to what motivated MacDonald to take apart Jewish DNA.

“I got involved in the movement, really, because I had these Jewish roommates. I just tried to fit in,” he says.

In a footnote to one of his books, MacDonald recounts being recruited to give a speech by his leftist friends, who he says were concerned that the movement looked too Jewish. “I was recruited to give a talk in which I was to explain how an ex-Catholic from a small town in Wisconsin had come to be converted to the cause.”

Thirty years after feeling like a token non-Jew in a purportedly Jewish political movement, MacDonald cited his experience as proof that Jews in general are compelled to challenge traditional American ideals by taking over political and cultural movements fronted by token non-Jews. (It seems remarkable, however, that he doesn’t appear very interested in exploring how such personal experiences may have colored his theories. Instead, his college days are merely empirical evidence for the point he wants to make.)

After the aborted jazz career and his involvement in leftist politics, MacDonald entered graduate school at 32 and began feeding mice to wolf cubs. By that time, 1976, most of his colleagues were buzzing about E.O. Wilson and sociobiology. MacDonald was drawn to the new field, and he went on to apply sociobiological ideas to childhood development. Although today he calls himself an evolutionary psychologist, he’s never given up the field’s old label. He points out that he continues to teach a class with the title “sociobiology.”

But MacDonald says he also became interested in the way people are driven to form groups. He was sympathetic to the idea that natural selection predisposed people to act differently towards people inside and outside those groups. In 1988, he published a book about the ancient Spartans and how their group mentality seemed a good example of this. “No one complained, of course,” he says.

But then, in 1990, he saw an L.A. Times article about an enclave of Jews living in Wyoming. The article got him thinking about how Jewish people, after scattering across the globe, still maintain a highly cohesive culture despite being vastly outnumbered by the people they live among. How do they do it? MacDonald wondered.

“It just clicked,” he says. “It was a strategy — a way of getting on in the world.”

He had the chapters of his first book planned by the end of the week.

What MacDonald set out to do in his book about Judaism turned into a trilogy published between 1994 and 1998. Researching the series sent him chasing down arcane Jewish history, from 16th-century Poland to medieval Spain, from the Babylonian exile to Hitler’s Germany. The result was three fat, heavily footnoted books filled with scientific jargon and some of the most explosive statements about Jewry since Mein Kampf.

In the first book, MacDonald lays out his Darwinian arguments about Judaism and Jewish groupthink. Titled A People That Shall Dwell Alone: Judaism as a Group Evolutionary Strategy, MacDonald suggests that natural selection gave humans the desire to live in cohesive groups, communities that would remain endogamous (marrying within the fold) and encourage cooperation between their members. MacDonald claims Jewish genes show a homogeneity despite the geographic separation of different Jewish populations, proving that whatever historical strategies Jews had come up with to remain endogamous were highly successful. His object, MacDonald writes, is to figure out what it was about Jewish culture that had enabled Jews to maintain that cohesion and genetic sameness. And he claims to find it, primarily, in the religion and laws of Judaism itself.

MacDonald makes heavy use of the Talmud, the Tanakh (what Christians call the Old Testament), and other primary Jewish texts that command Jews to maintain racial purity and have lots of children. This concern with procreation, he writes, is key to understanding Jewish history. The ancient texts also suggest that Jews formed an ideology based on their group mentality. So their very identity as Jews was reliant on their being a separate, chosen people that had been scattered to the four winds. With this ideology, Jewish culture maintained its closed nature even as Jews found themselves living in far-flung places and among strange peoples.

Having established that Jews were able, through religious and legal codes, to maintain their cohesiveness, MacDonald then turns to how the Jewish group strategy became, perhaps unwittingly, a eugenics program to improve the race through selective breeding.

In a cynical reading of the Talmud, the complex legal and religious code of Judaism, MacDonald says that such texts weren’t difficult to master for any rational reason; they were arcane because they served as a sort of ancient version of the SAT test. Young men with the intellect to master the Talmud’s intricacies were recommended to fathers looking to marry off their daughters. “This massive set of writings,” MacDonald writes, “is therefore substantially unnecessary in terms of fulfilling any purely religious or practical legal need.”

Instead, MacDonald argues, such texts were primarily necessary for deciding which intelligent young men got to mate with the most eligible young brides, helping to spread smart genes throughout the population. The result of this unconscious eugenics program, MacDonald says, is that today some Jews have higher IQs. “Research suggests an average IQ of Ashkenazi Eastern European origin Jewish children in the range of 117,” he writes.

In his second volume, MacDonald goes on to discuss how outsiders reacted to this Jewish evolutionary strategy. Titled Separation and Its Discontents: Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Anti-Semitism, the book attempts to find a Darwinian explanation for why, in so many historical periods and in such different places, Jews were the target of hatred.

MacDonald proposed in his first book that natural selection had bestowed on human beings the tendency to marry within a group and cooperate with that group’s members. The flip side of that argument is that they would be met with suspicion and perhaps envy by members of other groups. Since Jews had not only maintained a separate culture but had also boosted their fortunes by breeding for intelligence, this Darwinian view predicts that non-Jews would react to Jewish success with deep animosity. And that’s just what Jews encountered.

In other words, in MacDonald’s view, anti-Semitism becomes a perfectly logical by-product of biological processes encoded in human DNA, rather than, for example, an irrational revulsion harbored by people who believe that Jews murdered their god. (MacDonald does acknowledge, however, that Christians’ angst over deicide contributed to their anti-Semitism.)

In another chapter, MacDonald credits Adolf Hitler with recognizing that Judaism was an evolutionary group strategy. The Nazi response, MacDonald writes, was to mimic Jewish collectivism and group identity. Nazis adopted Jewish strategies to battle Jewish success. Like Jews, argues MacDonald, Nazis put heavy emphasis on endogamy and cooperation in the group:

“There is an eerie sense in which National Socialist Nazi ideology was a mirror image of traditional Jewish ideology…Like the Jews, the National Socialists were greatly concerned with eugenics. Like the Jews, there was a powerful concern with socializing group members into accepting group goals and with the importance of within-group altruism and cooperation in attaining these goals.”

How did Jews react to anti-Semitism? To a certain extent, some anti-Semitism was not such a bad thing, MacDonald says. Being surrounded by simmering hatred helps you maintain your group identity and keeps your members in line. “Recently, the Holocaust has assumed a preeminent role in this self-conceptualization. A 1991 survey found that 85 percent of American Jews reported that the Holocaust was ‘very important’ to their sense of being Jewish…Within Israel the Holocaust acts as a sort of social glue,” MacDonald writes.

One Jewish strategy to combat anti-Semitism, MacDonald says, is a healthy dose of self-deception. Evolutionary psychologists often evoke the concept of self-deception when they discuss relationships between human beings. If, in the ultra-Darwinian view, everything boils down to spreading one’s genes and struggling to survive, then humans commonly deceive themselves that their actions have higher motives. So it is with Jewish evolutionary group strategies, MacDonald writes: “Reflecting self-deception and negative perceptions of the outgroup, Jewish intellectuals have held on to the idea of the Jew as outsider and underdog long after Jews had achieved vastly disproportionate success in America.” The ability to deceive themselves about their wealth and influence, he says, allows Jews to continue to portray themselves (and think of themselves) as an oppressed minority.

MacDonald repeatedly reminds his readers that if his descriptions of Jews as subversive and self-deceptive seem repellent, that’s just what you’d expect from an evolutionary group strategy. “I have noted several times that the human mind was not designed to seek truth but rather to attain evolutionary goals,” MacDonald writes in a standard sort of Darwinian mantra.

MacDonald launches his real fireworks in his third volume, in which he continues to propose “scientific” proofs of the supposed Jewish conspiracy. Titled The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements, MacDonald suggests that in order to combat anti-Semitism, Jews have, as part of their evolutionary strategy, dominated various European and American 20th-century intellectual movements, sometimes holding up token non-Jews to mask their control, and that these movements were used to further Jewish ends.

Through their prominent positions in radical politics, psychoanalysis, and cultural studies, he writes, Jews called into question “the fundamental moral, political, cultural, and economic foundations of Western society. It will be apparent that these movements have also served various Jewish interests quite well.” Furthermore, in each of the movements, Jews promoted their interests as objective science, he says. (Which, many would argue, is a distinctly ironic position for a sociobiologist to take.)

MacDonald reserves special venom for Stephen Jay Gould and Tufts University psychologist Richard Lerner, who have each ridiculed sociobiologists and particularly those, like MacDonald, who tend to draw conclusions from IQ data. But that’s just window dressing for MacDonald’s grand finale, which occurs in the trilogy’s final chapter.

The result of all those subversive Jewish-controlled intellectual movements has been a dangerous undermining of Western culture, which MacDonald blames for lots of deaths all over the world:

“In the 20th century many millions of people have been killed in the attempt by Jews to establish Marxist societies based on the ideal of complete economic and social leveling, and many more millions of people have been killed as a result of the failure of Jewish assimilation into European societies.”

In other words, Jews brought the Holocaust on themselves and are responsible for the millions killed by Communist regimes?

“Well, yeah, I think that’s not unfair,” MacDonald says.

But he’s not finished. In The Culture of Critique he goes on with his dire warnings: “The United States is well on the road to being dominated by an Asian technocratic elite and a Jewish business, professional, and media elite,” MacDonald writes, predicting that the result will be an outbreak of race warfare.

As Jews have attacked Gentile ideals, he writes, “the result has been a widening gulf between the cultural successes of Jews and Gentiles and a disaster for society as a whole” that has led to “the present decline of European peoples in the New World.”

“He’s so far-out. He is just so factually wrong, it’s mind-boggling,” says University of Montreal anthropologist Ken Jacobs.

Jacobs is one of the small number of people who have actually read McDonald’s trilogy. In fact, he’s read each of the volumes at least twice. Jacobs says he’s prepared a 300-page manuscript detailing all of MacDonald’s errors. Jacobs is working with two other colleagues to produce a book on MacDonald, and he says a publisher has expressed interest in the project. Speaking by telephone, Jacobs sounds as if he can’t decide whether to laugh or scream — just talking about MacDonald, he says, exasperates him.

“I’m wondering whether to just back off, because I don’t want to fan the flames. If everyone’s going to write him off as a nutcase, why write a book? He just infuriates me, so I can’t read a page of any of the books without going off,” he says.

“To say that Jews are somehow homogeneous across the entire diaspora is completely fallacious,” he adds. “There is so much incredible genetic heterogeneity within the Jewish community — any Jewish community. To ascribe any kind of behavior, especially behavior over the past 2,000 years, to a genetic component — it’s just absurd.”

Jewish people simply don’t exhibit the genetic homogeneity that MacDonald ascribes to them, Jacobs says. The only Jewish subgroup that does show some homogeneity — descendants of the Cohanim, or priestly class — makes up only about 2 percent of the Jewish population. Even within the Cohanim, and certainly within the rest of the Jewish people, there’s a vast amount of genetic variation that simply contradicts MacDonald’s most basic assertion that Jewish genetic sameness is a sign that Judaism is an evolutionary group strategy.

Adds Tufts’ Richard Lerner: “Most people who know Jews and Judaism know that there is not only cultural and political diversity but also tremendous physical and physiological diversity among Jews.”

Lerner has long known MacDonald and points out that just 15 years ago, MacDonald published papers with a very different message: That genetics had little to do with how young children develop psychologically. Now, Lerner says, MacDonald’s sociobiological views have caused him to take an ultra-Darwinian position that is simply wrong.

“Kevin is not a biologist and he really doesn’t do empirical research in this area. These are ad hoc opinions based on a misreading of the biological literature and some ill-founded ideas on Jews and Judaism,” says Lerner.

Anyone with even a high school understanding of genetics should be able to see how wrong MacDonald’s ideas are, he points out. It’s in high school that one learns about how a genotype — the sequence of genes that are encoded in a person’s DNA — produce enzymes that in turn influence the chemical reactions that, under the ever-present influence of environmental factors, produce a phenotype — the actual physical characteristics of an organism.

“No gene specifies what a final product will be,” Lerner says. “The genotype represents a range of possible outcomes” that are dependent on interactions inside and outside the cell as well as outside the organism. “The premise that there could be some social strategy for getting genes to work in a particular way is ridiculous.”

Lerner says that the number of genotypes that a single human is potentially able to impart to the next generation is so large that to express it would require a 1 followed by 3,000 zeroes. (Multiply the total number of humans who have ever lived by the number of stars in the universe and you still wouldn’t come close to such a number.) “So when there’s so much genetic diversity and you consider the fact that any one genotype can lead to an infinite array of phenotypes, these ideas that there are superordinate genetic effects that apply across huge categories of humanity is errant nonsense. And that is the premise upon which he builds everything.”

Lerner says that since MacDonald’s basic assumption is so faulty, it’s simply a waste of time to consider his obviously flawed readings of Jewish culture as a eugenics program. “What would you like me to make of that nonsense? He makes an absurd premise and then derives from it illogical consequences. And then for me to try to respond — in doing that I’m giving credence to the original premise, which is absurd.”

Even if one did take seriously MacDonald’s view that the Talmud and proscriptions against intermarriage were combined in some sort of breeding program, MacDonald’s got things backward, says Montreal’s Jacobs. Those restrictions were imposed, he points out, only because Jewish people were doing the exact opposite. “If you look at the rabbinical letters from the 13th century to the 18th century, they’re constantly warning Jews about interbreeding. You don’t warn people about doing things that they don’t have a predilection to do in the first place,” he says. “Why in the 14th century, for example, in the Rhineland, why were Jews made to wear a sign, a symbol? It’s because you couldn’t tell a Jew unless you made them wear a sign. They looked like everybody else. Why? Because they were breeding with everybody else.”

Even MacDonald’s academic supporters (and online discussions suggest that there are a few) say he makes major errors in his works.

Anthropologist John Hartung, who criticizes both Jewish and Christian ideology in his own work, wrote a positive review of MacDonald’s first book. But he says MacDonald’s biological arguments and use of IQ data are deeply flawed. If MacDonald is attempting to explain the genetic sameness of all Jews, why does he single out only Jews of Eastern European origin and say they score well on IQ tests? IQ tests done in Israel on Jewish people from all over the world, Hartung says, result in the same scoring averages as are found among non-Jews. (Lerner and many other scholars question the value of intelligence testing in the first place, saying IQ tests aren’t objective tools and don’t measure a real “thing” consistent across cultures.)

Hartung also dismisses MacDonald’s assertion that anti-Semitism can be understood as a logical result of biological processes. If that’s the case, then why haven’t other diaspora peoples — such as those from India and Armenia — experienced the same historically and geographically consistent hatred that’s been heaped on Jews?

As for vast Jewish conspiracies to denigrate Western culture, Lerner says MacDonald himself admits to inconsistencies in his theories but then brushes them aside. For every Jew involved in psychoanalysis or radical politics, there are others who criticize those movements. To perceive such movements as “Jewish” is simply a mistaken interpretation.

“One of MacDonald’s heroes has to be Dick Herrnstein the late coauthor of The Bell Curve and a Jew,” says Lerner, referring to a highly controversial book that claimed blacks are inherently less intelligent than members of other racial groups. “If it was such a Jewish cabal in which all these nonvarying people were conspiring together to promote their particular invariant genotype, then why are there other people on the other side of the issue?” Lerner points to a footnote in MacDonald’s trilogy where he admits that a number of Jewish scholars have been involved in sociobiology and conservative political movements. “Even though he acknowledges that, for some reason it doesn’t make him see the folly of his statements about a monolithic Jewish program,” Lerner says.

A MacDonald supporter wrote to him recently to warn him that his theories about Jewish conspiracies made it difficult to defend him. University of Arizona psychologist Aurelio J. Figueredo wrote that he tries to convince others that MacDonald’s views in the first two volumes are scientific and not anti-Semitic, but he complained that the third volume makes that position untenable. “By emphatically disapproving of intellectual movements which you explicitly state were designed to counter anti-Semitism, does that not imply that you approve of anti-Semitism?”

That’s exactly the case, says MacDonald critic Robert Pois, a professor of history at the University of Colorado, Boulder. ” MacDonald may have convinced himself and others that he’s being coldly scientific,” Pois says. “I think he genuinely has convinced himself he is not anti-Semitic. But he’s wrong about that.”

What MacDonald ends up ascribing to biology, his critics say, is better understood as popular allegory, the myths that get handed down with a lot more faithfulness than chromosomal codes.

“The durability of folklore, that’s what it boils down to,” says Jacobs. “It’s not to be underestimated. We keep creating the same myths over and over and over, and we re-create it in another jargon. That’s what’s going on with Kevin.”

If Jews have succeeded in urban societies, says Lerner, it’s not because they contain a gene for higher intellect. “Culture is a very strong force,” he says. “If you look at why Jews have done well, it’s because they come from a 5,000-year culture that focused on carrying with them the one thing they could carry with them. They couldn’t carry with them money, or property, or ownership of the businesses that were taken away repeatedly, not just in the Holocaust. They could carry with them the skills to learn. Now, if the Holocaust, which is probably the greatest single intervention that’s ever been attempted in the history of humanity, couldn’t change Jews’ culture about learning, then what could? So the fact that Jews do better than other groups is not because they have better genes, but they have, I think, some commonality of culture.”

MacDonald, however, has been influenced by the beliefs of sociobiology — now going by the name evolutionary psychology — which looks to the human genome for answers that scholars previously ascribed to culture.

Marc Caplan, an Anti-Defamation League research analyst in New York, says he’s currently working on a report about MacDonald for the ADL. “MacDonald’s formulated an academic vocabulary for prejudice,” Caplan complains. “The fact that Jews are being indicted in the name of this science calls for a serious review of evolutionary psychology.”

“Today, I want to talk about IQ,” MacDonald says as he puts a transparency on the classroom’s overhead projector.

MacDonald’s voice doesn’t travel far into the large room, which is the shape of a giant pie wedge, and students strain to hear him. The desks radiate away from him in arcing rows and up a slightly sloping floor. About two-thirds of them are filled with students, who, judging by their questions, seem most eager to find out which parts of MacDonald’s lecture might show up on the developmental psych midterm.

“IQ is very important,” MacDonald says. “IQ is probably the most important individual human difference that we deal with.”

He describes the history of IQ testing, starting with its 1905 invention by Alfred Binet who wanted a way to identify French schoolchildren in need of special tutoring. (Binet didn’t intend for his Intelligence Quotient to be interpreted as a measurement of a tangible, objective mental attribute, but that’s just what it’s become.)

MacDonald tells his students there’s no reliable way to raise children’s IQ, and then mentions that there was a famous book published a few years ago called The Bell Curve.

MacDonald makes a brief mention that the book was controversial, but then he puts a chart from the book on his projector with the implication that its data represents good science. The chart shows how lower IQ predicts that an individual will have lower income, more children, and more illegitimate children.

“The dull ones are more fertile — what does this mean for our future?” MacDonald asks offhandedly, and his students laugh.

Authors Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray collected hundreds of studies on IQ and different ethnic groups, and claimed that the data suggested that Asians had slightly higher average intelligence than whites, who in turn outscored blacks. The writers claimed that these were the result of genetic differences, and that if blacks were inherently less intelligent, it was a waste of time to promote affirmative action in schools and industry.

But many scientists accused Herrnstein and Murray of using highly questionable data and fudging their numbers to match their prejudices. The authors had relied heavily on IQ data developed by Richard Lynn, a controversial psychology professor at the University of Ulster in Northern Ireland who espoused the view that the poor and the ill are “weak specimens whose proliferation needs to be discouraged in the interests of the improvement of the genetic quality of the group, and ultimately of group survival.”

Critics pointed out that Lynn had received $325,000 from the Pioneer Fund, created in 1937 by several millionaires to back research in heredity, eugenics, and “race betterment.” (Among its founders was Wickliffe Draper, a New York textile tycoon who advocated sending blacks to Africa.) Lynn served as an associate editor of Mankind Quarterly, a publication dedicated to “race science” that also received money from the Pioneer Fund. In the 1970s, the quarterly’s editorial advisers included Baron Otmar Von Verscheur, who had been director of the genetics and eugenics program at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin during World War II. While at the institute, the baron recommended one of his students, Joseph Mengele, for a doctor’s post at Auschwitz.

Critics also charged that Lynn had distorted African psychometric tests, ignored data that showed some African blacks had scored higher than African whites, and falsely concluded that African blacks average a miserable 69 on IQ tests. “Lynn’s distortions and misrepresentations of the data constitute a truly venomous racism, combined with scandalous disregard for scientific objectivity,” wrote Northeastern University’s Leon Kamin. “It is a matter of shame and disgrace that Herrnstein and Murray, fully aware of the sensitivity of the issues they address, take Lynn as their scientific tutor and uncritically accept his surveys of research.”

Still, Kevin MacDonald calls The Bell Curve a “great book.” And he himself turns to Richard Lynn for the most important underpinnings of his thesis on Judaism.

It’s Lynn’s work that MacDonald cites when he says that the IQs of Ashkenazi Jews are a standard deviation higher than white IQs. Indeed, MacDonald includes one of Lynn’s Mankind Quarterly articles in the bibliography to his book, A People That Shall Dwell Alone.

MacDonald also makes numerous references to the work of Canadian researcher Philippe Rushton and even makes a point of thanking Rushton in his books’ forewords.

Rushton is another Pioneer Fund recipient — he’s received more than $500,000 — who asserts that there’s an inverse correlation between brain size and penis size. He claims that blacks’ larger penises are an indication not only of lower intelligence but of greater promiscuity — a conclusion he reached based on interviewing just 50 black students at the university where he teaches. Rushton’s theories have made him such an intellectual pariah that in 1989 he was investigated, but not charged, under Canadian hate-propaganda laws.

Sander Gilman, a University of Chicago cultural historian, argues that in the final analysis, MacDonald’s work amounts to little more than a rehash of discredited theories about Jewish breeding that eugenicists have been making for more than a century.

In his book Smart Jews: The Construction of the Image of Jewish Superior Intelligence, Gilman writes that Sir Francis Galton, the father of eugenics, asserted more than a century ago that Jews were breeding for intelligence — although a negative, cunning sort of intelligence — by encouraging Talmudic scholars to procreate.

Gilman also cites conservative writer Ernest van den Haag, who in 1969 revived some of Galton’s views in language that sounds remarkably like MacDonald’s: “Literally for millennia, the brightest Jewish males had the best chance to marry and produce children, and their children had the best chance to survive infancy.”

Gilman draws parallels between MacDonald’s ideas and the 1930s writings of German anthropologist Hans F. K. Gunther, whose book on Jews, says Gilman, was a “standard work of Nazi science during the 1930s and 1940s.” (Gunther was also a member of the Northern League, a group founded by Mankind Quarterly publisher Roger Pearson to promote “the interests, friendship, and solidarity of all Teutonic nations.”)

According to Gilman, Gunther “attempted to describe the ‘sensual,’ ‘threatening,’ and ‘crafty’ gaze of the Jew as the direct result of the physiology of the Jewish face and as reflecting the essence of the Jewish soul…For Gunther, ‘the considerable average intelligence which distinguishes the Jewish people’ was the result of the ‘selection among the Jews’ to have offspring who ‘were able to adapt to the specific conditions of life among foreign people’…Preselection for intelligence through millennia of anti-Semitism becomes one of the staples for the explanation of the ‘reality’ of Jewish superior intelligence.”

Concludes Gilman: “MacDonald recasts all the hoary myths about Jewish psychological difference and its presumed link to Jewish superior intelligence in contemporary sociobiological garb.”

With much of the world watching, Kevin MacDonald had painted himself into a corner. He had just implied that David Irving, the man who had flown him halfway around the world to testify in Britain’s High Court, was an anti-Semite.

The Long Beach academic was sitting in the witness-box and was being questioned by Irving. It was January 31 — early enough in Irving’s trial that British newspapers were still giving it daily coverage (eventually, its mind-numbing detail would chase away the world’s media, which only came back for closing arguments and the verdict).

It had been nearly a year since Irving first contacted him, asking MacDonald to meet him at a Costa Mesa talk sponsored by the Institute for Historical Review — a well-known U.S.-based organization of Holocaust deniers. MacDonald agreed to go, and has defended his decision by noting that the meeting was also attended by one of Irving’s most severe critics; not everyone in the room sympathized with the institute’s views.

Irving had noticed that MacDonald’s book Separation and Its Discontents claimed that Jewish organizations combat anti-Semitism by shutting down debate on Jewish issues, and cited the ADL’s attempt to have Irving’s latest book, Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich, suppressed. He said he could use MacDonald’s testimony to prove that various Jewish organizations were out to get him. MacDonald agreed to help.

Irving, who’s been described as a fascist British historian of fascism, had been both lauded for his knowledge of military history and attacked for his apologist treatments of Hitler. Convinced that Hitler knew nothing about and did not order the Final Solution, Irving had been converted to outright Holocaust denial in the late 1980s by the findings of the controversial Fred Leuchter Jr., the execution equipment “engineer” (and pitiable subject of Errol Morris’ recent film Mr. Death) whose dismissive investigation of Nazi extermination camps was thoroughly debunked in a 1988 Toronto trial.

Deborah Lipstadt included Leuchter and Irving in her book, Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory, in which she traces the history of Holocaust denial from the days immediately after the war ended in Europe. Few events in human history are as well documented as the Holocaust, but from the beginning it was questioned by apologists trying to exonerate Hitler and the Nazis.

Lipstadt writes in explaining her motivation for researching the book that, by the early 1990s, the strategy of simply ignoring the deniers was no longer working: Revisionists had been targeting college campuses with bogus information, and too many young people were becoming doubters. Of all the people who promoted denial, Lipstadt wrote, Irving was among the most alarming: “Irving is one of the most dangerous spokespersons for Holocaust denial. Familiar with historical evidence, he bends it until it conforms with his ideological leanings and political agenda. A man who is convinced that Britain’s great decline was accelerated by its decision to go to war with Germany, he is most facile at taking accurate information and shaping it to confirm his conclusions…He demands ‘absolute documentary proof’ when it comes to proving the Germans guilty, but he relies on highly circumstantial evidence to condemn the Allies.”

Despite those strong words, Irving didn’t sue Lipstadt and her publisher Penguin Books for libel until, in 1996, it was reported that Lipstadt had helped pressure St. Martin’s Press to drop its publication of Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich.

MacDonald decided to help him prove that Lipstadt was a typical Jewish activist professor who was taking part in the kind of evolutionary group strategy MacDonald had described. “Irving has been prevented from publishing his original archival research, from traveling to several countries, and even from giving lectures…Deborah Lipstadt has contributed to this effort at censorship. My statement to the court and my entire testimony in court involved this issue, not the Holocaust or the culpability of Hitler,” MacDonald wrote in an online posting recently.

Soon after agreeing to participate, however, MacDonald had grave doubts about his decision.

Irving sent him an 800-page report by historian Richard Evans that seemed a devastating litany of Irving’s misrepresentations and distortions. Irving teased MacDonald for his lack of faith, and assured him that he could take Evans apart under cross-examination.

Satisfied that he was testifying for the right reasons — to protest the censoring of a legitimate author by an activist professor who had hidden her real motives — MacDonald flew to London in January to take his place in the historic trial.

Irving paid for his flight, but didn’t pay him an expert witness fee. MacDonald took his wife and stayed at Irving’s apartment, which he shares with a female companion and his six-year-old daughter. (Irving, who is something of a showboat, used a personal Web site to deliver daily updates on his trial as well as regular reports on his daughter’s day.) MacDonald says Irving was incredibly busy, not only with the trial but with a crush of media interviews, and slept only three or four hours a night.

On the day MacDonald testified, it was obvious from the outset that Irving was mainly interested in using the Long Beach professor to help him read into the record several less-than-stunning documents. Irving seemed to be trying to prove with the letters and newspaper clippings that, by denigrating him in her book, Lipstadt was serving a larger network of Jewish organizations. MacDonald, meanwhile, did what he could to bolster that argument. It was clear to him that she was part of some sort of larger conspiracy.

And then MacDonald made what seemed a serious misstep.

Irving asked him to consider the various documents he had read into the record and render a general opinion: Did he believe the documents showed that for a decade Irving had been a target of a “group strategy that has been evolved by the Jewish communities around the world to protect themselves or to preserve their interests?”

MacDonald responded: “Yes, I think that anti-Semitism is, you know, a perennial problem, and Jewish organizations have developed very sophisticated ways of dealing with it…They do quite a job, obviously, of suppressing it, yes.”

Irving apparently realized that MacDonald had put him in a difficult position. He had asked MacDonald to affirm that Jewish groups had targeted Irving, and MacDonald had agreed, saying that Jewish groups target anti-Semites.

Irving tried to save the situation: “Whom do you mean by anti-Semites: people who go round scoring swastikas on synagogues or people who have a genuine grievance?” Irving’s own witness, it appeared, had labeled him an anti-Semite. But he moved quickly to correct himself.

MacDonald: “Well, yes, the term they will use is very broad…I am not saying, I am not implying that you are an anti-Semite.”

British papers didn’t seem to know what to make of the testimony, reporting the next day only that the American professor didn’t think Irving was anti-Semitic. Lipstadt’s lawyers didn’t even bother to cross-examine MacDonald. Judge Gray, in his lengthy decision condemning Irving’s bigotry, mentions MacDonald in just a few words, saying that “the assistance which I derived from his evidence was limited.”

It was all rather anticlimactic, MacDonald admits.

After his return to Southern California, it was as if he’d never left. His involvement in the Irving trial was generating no phone calls or letters of protest. Other than his continuing battles on the Internet over his ideas, MacDonald rapidly slipped back into his regular routine.

“Things have calmed down completely,” he says.